Lewis BaltzMission Viejo, 1968gelatin silver printimage: 14.5 x 21.4 cm (5 11/16 x 8 7/16 in.)The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Lewis Baltz, 1972.219© Lewis Baltz.

Lewis BaltzMission Viejo, 1968gelatin silver printimage: 14.5 x 21.4 cm (5 11/16 x 8 7/16 in.)The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Lewis Baltz, 1972.219© Lewis Baltz.Is there such thing as a boring photo? Martin Parr’s series of Boring Postcards books, which collected photographs of banal architecture, evaded the question with a camp factor that distracts the reader from the ennui of yet another hotel room or highway rest stop. But as an aesthetic, the brutal and often Brutalist tedium of such images owes more than a little to minimalism – and to photographer Lewis Baltz. Inspired by the work of Sol Lewitt, Richard Serra and Donald Judd (all of whom have pieces on display here for comparison), Baltz was one of the first photographers to seriously embrace minimalism, and the resulting Protoypes are a fascinating body of work that speaks volumes about the emptiness of American life circa 1967 – and now.

Lewis BaltzLaguna Niguel, 1970gelatin silver printsheet: 13.81 x 21.59 cm (5 7/16 x 8 1/2 in.)Laguna Art Museum Collection, Anonymous gift, in memory of Beula Prince© Lewis Baltz.

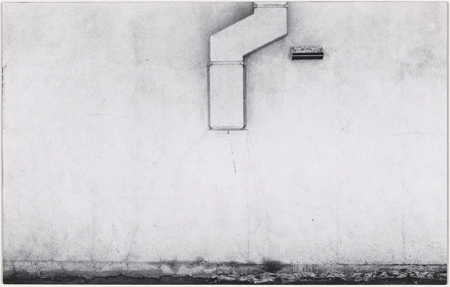

Lewis BaltzLaguna Niguel, 1970gelatin silver printsheet: 13.81 x 21.59 cm (5 7/16 x 8 1/2 in.)Laguna Art Museum Collection, Anonymous gift, in memory of Beula Prince© Lewis Baltz.Baltz sought to “refute photography’s apparently essential character as a means of making images of the three-dimensional world.” He did this by taking the bold liberty of removing one dimension. Many of the subjects in Prototypes are shot straight ahead, eliminating perspective cues and for the most part eschewing shadow. Thus the most mundane of subjects – a plaster wall with descending duct work, a parking lot – become evocative black and white abstractions.

The country that Baltz sees in these pictures is bleak and devoid of personality. The bas-relief like form of a soda pop bottle on a whitewashed billboard is all that remains to identify the product in Gilroy 1967. If American cities today seem more and more homogenized, the same unimaginative franchises lumbering over the same highways across the land, Baltz’s vision of late ’60s commercial landscapes makes it obvious that this isn’t a new phenomenon. Automobiles seem to be the last bastion of individualism in the Baltz landscape, but even a white Buick, its elegant fins a mass-produced yet distinctive corrective to its bland surroundings, seems ready to be devoured by the gaping maw of a pitch-black wall.

Two views of a business called POINT REALTY convey both a dry humor and an existential despair. The name of the business ironically reminds you that there is no vanishing point in these flat images, no perspective, no life. But this lifeless sign also recalls the word paintings of fellow Californians Ed Ruscha, who was also fascinated by parking lots, and John Baldessari, the subject of a fantastic and frequently hilarious retrospective at the Met last year. (And if you ask me, Baldessari’s appropriation work anticipated Women Laughing Alone With Salad by decades.)

For all its bold modernism, Baltz’s vision has clear links to the photographic tradition of Walker Evans and Eugene Atget. Parking spaces, doorways and windows return again and again – metaphors for camera aperture, perhaps – yet while Evans and Atget found character and poetry in such details, what Baltz seems to find is a country standing still.

The final room in the exhibit showcases a late work that seems like a complete departure for the artist. In stunning contrast to the six-by-eight inch prints of Protoypes, Ronde de Nuit (1992), named after Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, is a thirty-nine foot-by-seven foot mural made of cibachrome panels. Baltz was given free rein over a bank of surveillance cameras at a police center, and the panels juxtapose grainy surveillance images with photos of surveillance employees. A far cry from the stark Prototypes, Ronde de Nuit similarly opens a window on a modern society saturated with images: What do we see? What do we look like?

Lewis Baltz’s Prototypes/Ronde de Nuit is at the National Gallery of Art until July 31, 2011.