(Universal Pictures)

(Universal Pictures)

For years, Washington, D.C. has suffered from a major identity crisis on the silver screen. Sure, there have been a lot great films—and a lot of not-so-great ones—that take place in D.C. But the plurality opinion of most native Washingtonians is that movies that take place in and around the District—whether they actually bothered to film here or not—completely miss the mark of D.C.’s unique cultural fabric.

The cliche of most D.C.-centric movies is that This Town is nothing more than a political hotbed for greedy, conniving politicians to conduct shady business deals and continue to power a corrupt government. This, of course, isn’t true (well, maybe), but it’s since become the commonality for most D.C.-set films. I blame Frank Capra’s so-called political masterpiece, Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, for setting the stage for decades of ridiculous (but sometimes ridiculously entertaining!) political dramas and thrillers that paint our town as a power-hungry political town. Don’t believe me? Just consult Washington Life’s list of the so-called “100 Best Washington Movies Ever” list and you’ll see that just about every politically charged “Washington Movie” has something to do with corruption, scandal, lies, deceit, morally despicable characters, etc. Just from the first 20: All the President’s Men, Wag the Dog, The American President, Thank You For Smoking, Charlie Wilson’s War, Nixon, Advise & Consent, Absolute Power.

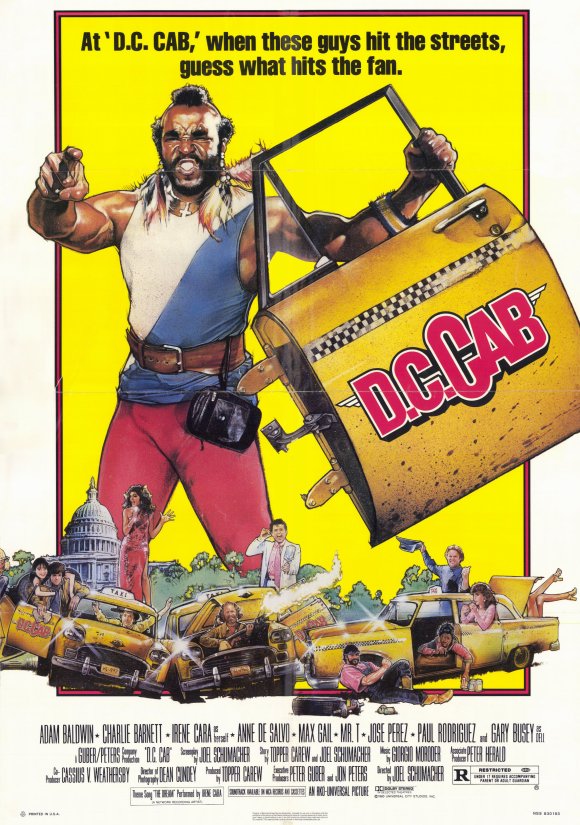

Of course, not all Washington movies portray D.C. in a bad light; many merely use the city’s iconic monuments and landscapes for, well, iconography. But the point is not many films have really tapped into the true fabric of D.C. culture like D.C. Cab did in the ’80s. Sure, on one level the film is a cheap, raunchy, and—by most accounts—bad ’80s comedy about a ragtag bunch of cabbies. But what makes D.C. Cab so great 30 years later is how it’s also a somewhat accurate cultural snapshot of D.C. in the ’80s.

The film’s central plot centers around a run-down cab company—called D.C. Cab—that’s struggling to compete with the far more lucrative and popular Emerald Cab Company. The film’s opening montage, which shows the daily routine of many of the film’s central characters, is meant to elicit laughs, but it’s also a deft portrait of just how hard it was for cabbies at the time: Opheila (Marsha Warfield) gets robbed on a nearly daily basis, Baba (Bill Maher) argues with tourists outside of the White House to try and get fares, and Samson (Mr. T) tries to lure his niece and others away from hitching rides in the luxurious car of one of the city’s rich drug dealers (clearly a Rayful Edmond stand-in). These, of course, were pertinent issues for cabbies in the ’80s who were merely trying to make an honest living.

(Universal Pictures)

(Universal Pictures)

As the Washington Post’s Clinton Yates aptly points out, the film’s portrayal of cabbie life echoes a lot of the same problems of D.C. cabbies today: “One of the more interesting parts of the film, though, were the issues that still ring true today. It’s still hard to make a living driving a cab. But if you know what you’re doing, you can get by. Sometimes it requires a hustle. And nearly 30 years after Charlie Barnett’s character Tyrone tried to pull an illegal fare at Dulles Airport in “D.C. Cab,” guys are still doing it.”

Indeed, if you’ve been following the ongoing struggles between the D.C. Taxicab Commission, taxi drivers, and Uber, the situation isn’t that far different than the central struggle of the film: D.C. Cab can’t compete with the glossier services and lower rates of the Emerald Cab Company (their shiny, polished green cabs and matching uniforms aren’t that much different than Uber’s fleet of luxury vehicles and suit-clad drivers). Meanwhile, they’re being threatened with shutdown by the city because D.C. Cab’s owner, Harold Oswelt (Max Gail), doesn’t have the financial means to keep his cab up to regulation. Sound familiar?

But what’s most significant about D.C. Cab—and what makes it one of the best D.C. films ever made—is how it utilized filming in locally-famous locations that represent a rich part of the city’s cultural history. The Florida Avenue Grill—the legendary U Street-area diner located at the corner of 11th Street and Florida Avenue NW—is the regular hangout for the city’s cabbies. It’s also the location of the film’s most well-known scene, an epic food fight between D.C. Cab’s and Emerald Cab’s cabbies. There’s still relics and photos from the film hung up around the Florida Avenue Grill to this day. The film’s other primary locations were also set in neighborhoods that hasn’t previously been featured on camera.

There’s many other facets of D.C. Cab that highlight how accurate a portrait of D.C. it is, but not all are good. There’s the film’s casually racist politics and tone that highlight the racial divide of D.C. in the ’80s—a problem that is definitely still alive and present today. And even the presence of the film’s lead character, Albert Hockeberry (Adam Baldwin), who migrates to D.C. to start a new life, can be seen as an indicator for the gentrification to come years later. But that just speaks to the rich cultural development and history of D.C. One that deserves more films like D.C. Cab that at least makes the effort to get it right.