The world premiere of Sanctuary, a new work for amplified, computer-modified percussion ensemble by Roger Reynolds (b. 1934), took place at the National Gallery of Art on Sunday evening. It was an event, the sort of concert that gets noticed by Alex Ross: alas, the element that would have sealed its place in history, an angry riot by perturbed listeners, did not happen. The mistake that caused the failure to obtain a true succès de scandale was in allowing the audience to hear the concert for free. Only paying listeners can really get outraged enough to hate challenging music. True, a number of listeners left before the full 80 minutes of the work had played itself out, often walking right across the stage area and past the performers toward the doors, but the only thing lost was part of their Sunday night, not $50.

The world premiere of Sanctuary, a new work for amplified, computer-modified percussion ensemble by Roger Reynolds (b. 1934), took place at the National Gallery of Art on Sunday evening. It was an event, the sort of concert that gets noticed by Alex Ross: alas, the element that would have sealed its place in history, an angry riot by perturbed listeners, did not happen. The mistake that caused the failure to obtain a true succès de scandale was in allowing the audience to hear the concert for free. Only paying listeners can really get outraged enough to hate challenging music. True, a number of listeners left before the full 80 minutes of the work had played itself out, often walking right across the stage area and past the performers toward the doors, but the only thing lost was part of their Sunday night, not $50.

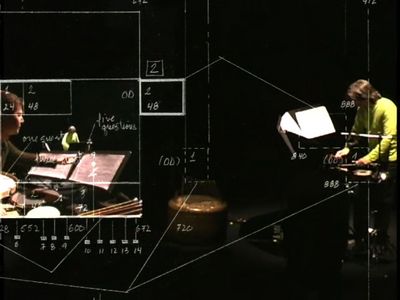

An encouragingly large and interested audience filled the East Building’s auditorium to hear the composer try to explain what the piece is all about and how it came to be. He credited his granddaughter with the initial idea, when during a game involving impersonation of scary monsters, she proclaimed a room to be a sanctuary where “monsters can’t come in.” The idea was to transform the magnificent space of the East Building atrium with sound, initiated by the musicians striking traditional percussion instruments as well as all kinds of junk, impulses which were then processed by a computer and amplified through speakers placed around the space. There is a half-baked, quasi-mystical side to the work, in which the players pose questions to a waterphone made from parts of an old clothes dryer, called with self-belittling irony The Oracle. It has all been explained in Stephen Brookes’s preview article for the Post and in the program notes (.PDF file). Hearing the performance added surprisingly little to one’s basic appreciation of what Reynolds was trying to do. The theory, truth be told, is more interesting than the practice.

Image by the Sanctuary Project, University of California at San Diego