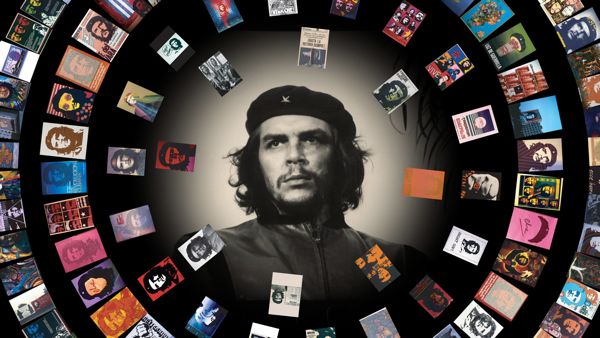

With the recent cinematic dramatizations of the life of Che Guevara, from his early days as a road tripping med student in the excellent The Motorcycle Diaries to Steven Soderbergh’s lengthy version of his revolutionary years in the four and a half hour biopic that just premiered at Cannes, an unusual perspective was obviously necessary to any documentary version of his story to keep it from seeming stale or overly academic in comparison. And the makers of Chevolution have done just that, constructing a history of the man that not only succeeds in avoiding either blind lionization or reactionary condemnation, but also looks at him with the lens through which we most often see him. Literally.

Getting a handle on who Che Guevara was, and what he means now can’t be as simple as rote biography when the myths and legends that surround his legacy are so outsized. As one South American laborer states during the film, he’s not a religious man, but if he was, Che would be his god. How does one begin to cut through that kind of inflated image? By using the singular iconic image that helped make him more symbol than man as the starting point. You may have never heard the name Albert Korda, but you know his work. The ubiquitous image of Che Guevara that adorned revolutionary posters throughout the turbulent late 1960s, and increasing numbers of consumer products in the decades since then, from T-shirts to bikini bottoms to baby booties, was shot by Korda in 1960 at a memorial service for the victims of a tragic port explosion some believed may have been orchestrated by the United States. The documentary traces the paths of both Guevara and Korda in their lives leading up to that moment, and in the years after, finally analyzing the complex relationship between the image and its widespread use as a symbol of revolution and rebellion to both true believers and to a youth culture more conscious of fashion than of the course of Latin American revolutionary history.