In which DCist interviews area scientists, researchers, and academics on topics pertaining to natural and scientific interests. As Thomas Dolby would say: science!

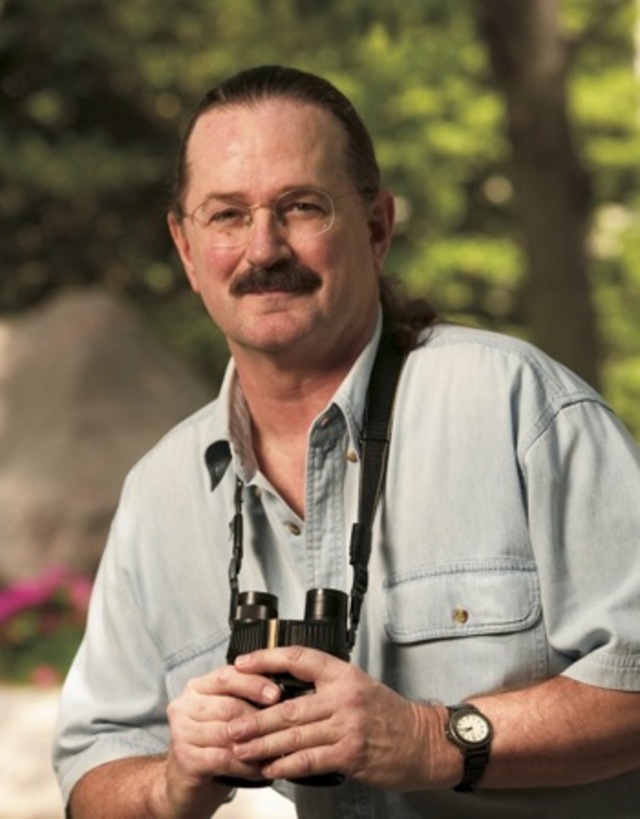

Jonathan Alderfer began his career as a bird painter in the 1980s by illustrating bird identification articles for the Los Angeles Audubon Society’s newsletter, The Western Tanager. He is the editor of National Geographic’s Complete Birds of North America, published in 2005, and co-editor of the 5th edition of their Field Guide to the Birds of North America, published in 2006. As an independent field ornithologist he has published illustrations in scientific and popular publications such as Audubon Magazine, North American Birds, Bird Watchers’ Digest, Birding, and National Geographic Magazine. Alderfer co-authored Birding Essentials, which was published in 2007. Later this year, National Geographic will publish Illustrated Birds of North America, Folio Edition, a large-format illustrated guide.

Jonathan Alderfer began his career as a bird painter in the 1980s by illustrating bird identification articles for the Los Angeles Audubon Society’s newsletter, The Western Tanager. He is the editor of National Geographic’s Complete Birds of North America, published in 2005, and co-editor of the 5th edition of their Field Guide to the Birds of North America, published in 2006. As an independent field ornithologist he has published illustrations in scientific and popular publications such as Audubon Magazine, North American Birds, Bird Watchers’ Digest, Birding, and National Geographic Magazine. Alderfer co-authored Birding Essentials, which was published in 2007. Later this year, National Geographic will publish Illustrated Birds of North America, Folio Edition, a large-format illustrated guide.

Alderfer’s paintings appear in “Birds of North America,” a gallery exhibition of original and archived bird paintings by four illustrators, on display through May at the National Geographic Museum. Alderfer (whose work there is available for purchase) is the only modern illustrator in the group.

DCist: Are these works plein-air paintings? There is quite a bit of landscape in them.

Jonathan Alderfer: No, they aren’t. I think it’s an interesting distinction between illustration and fine art. I feel I do both types of painting, but this is pretty much illustration. In my mind, illustration is when somebody else is telling you what to paint. In fine art, there are no outside constraints.

When you receive editorial assignments, is the request for a specific bird you need to capture?

Sure. For the horned grebe, for example, there are five images here [in the Field Guide] to show all the variation within the species. You need to include all the plumages, different ages. A lot of species don’t look the same year round or they don’t look the same when they’re young versus when they’re adult.

When an editor says, I need a look at this bird, how do you start?

I was the co-editor of this book with John Dunn. We’re expert birders, so we know what needs to be shown, but I’m not the sole artist in the book. There are a lot of artists. So if we say to an artist, We need you to paint herring gull, there might be 15 plumages that we wanted to see. So we say, We need this, this, this, and this. The artist submits a drawing, and we tell him if he needs to work on the bill or work on the feet or some details. Then we go to the stage where we say, This drawing is ready—you can start painting now.

If you’re out in the field and you’re looking for an animal, are you looking for one iconic example or a bunch of really good examples of parts?

You want to try to paint an image that you’ve internalized over a period of decades, if you’ve been a birder for a long time. You develop an internal image of what that bird looks like. You need to get all the details right, so you’re not just going for a gestalt look of the bird. You need to get all the details, the way the bird stands or perches or flies.

You don’t want to duplicate a photograph, for instance, because that shows a bird in a split instance. It might have odd feather arrangement, it might have odd shadows or reflected light or backgrounds that are disturbing.