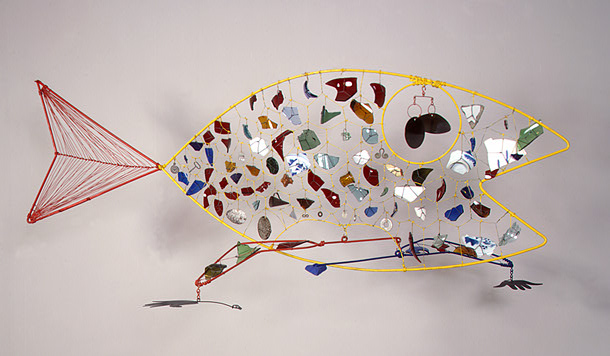

Alexander Calder, Finny Fish. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

Alexander Calder, Finny Fish. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.

Tonight at Politics & Prose, writer and angler Paul Greenberg will read from his new book Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food. It’s a book that’s swum into stores at just the right time, as people turn their minds more to the repercussions of our consumption. Farmed versus wild salmon; rising mercury levels in tuna; sustainability and ethics: there’s a lot to weigh up before we batter a bit of plaice and stick it next to some chips.

Greenberg has done something smart in his book: rather than succumb to the fisherman’s fetish of coming over all ADD and offering “a maze of all the different fish out there,” he’s focusing on four popular fish varieties. His menu reads salmon, bass, cod and tuna — those we see most in our market-places — all of which are on the cusp of domestication in some way. Apart from the fact that he’s adamant that some fish are strictly not suited to taming, Greenberg’s main concern isn’t extinction: it’s the loss of abundance in the wild.

Time it right, and you can encounter that impression of precious, jewel-like nature at the National Gallery of Art, with this delightful Finny Fish (1948). It’s by the American artist Alexander Calder (1898 – 1976), who worked variously as a sculptor, abstract painter and illustrator of children’s books. He was born into a fertile artistic lineage: his father and grandfather (who both shared his name) were important sculptors, and his mother was a portrait painter.

Calder worked originally as an engineer (he’d received a degree from Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey) and a work like Finny Fish is essentially a marriage of his technical-engineering and artistic minds. It’s dubbed a “mobile” (a term coined by Marcel Duchamp in 1931) and Calder’s “mobiles” (as well as their earth-bound counterparts the “stabiles”) revolutionized sculpture.