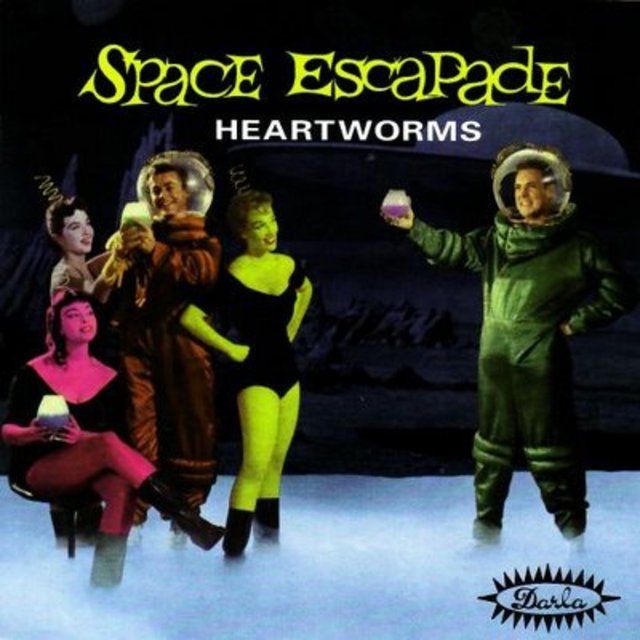

Secret History profiles classic D.C. albums in order to shine a light on the greatness of the District’s musical past. This installment focuses on Heartworms’ indie pop gem Space Escapade (Darla, 1995).

Secret History profiles classic D.C. albums in order to shine a light on the greatness of the District’s musical past. This installment focuses on Heartworms’ indie pop gem Space Escapade (Darla, 1995).

As far as side projects go, Heartworms were an especially charming diversion. Featuring members of Velocity Girl and Chisel, two of D.C.’s sharpest ’90s-era outfits, this four-piece specialized in noise pop for now people, jangly chords and girl-group harmonies rubbing shoulders with space-case drones and blissed-out shoegaze. One of the first acts ever released by the esteemed Darla label, Heartworms — along with Velocity Girl, Black Tambourine, Unrest and others — bolstered the District’s reputation as a source of great indie pop, and were further proof that not all of D.C.’s rock acts were cast in the (admittedly awesome) post-hardcore mold.

At the center of Heartworms were Archie Moore, guitarist/vocalist for both Velocity Girl and Black Tambourine, and Belmondo guitarist/vocalist Patricia Roy; the two first started Heartworms in the early 1990s, while living in Prince George’s County. “Trish and I lived in a house in Oxon Hill,” says Moore. “It was where Velocity Girl practiced every weekday, so we had guitars, amps and drums at our disposal. At some point, the two of us started playing guitar together for fun, mostly just plucking out droning, Yo La Tengo-esque figures over and over, with lots of tremolo, very quietly. We started accumulating a little repertoire of drones and song parts. We were very much into the vibe of the Yo La Tengo album Painful, as well as Luna’s Bewitched.”

However, in addition to indie rock contemporaries like Yo La Tengo and Luna, Moore and Roy reached back to earlier pop perfectionists for inspiration. “For reasons that are now obscure to me,” says Moore, “I bought some basic studio equipment and a drum machine, and the first things I recorded with it, with Trish, were covers of ‘Girl Don’t Tell Me’ by the Beach Boys, and ‘Sunday Girl’ by Blondie, just to learn how to use the gear. I think we did those in an afternoon. I was pretty obsessed with Flying Saucer Attack, so I tried to emulate their fried guitar haze. The Beach Boys were my favorite band then, and Blondie’s Parallel Lines was the first album I ever owned.”

Eventually, the drifting melodic vapors began to coalesce around a semi-solid core, and Moore and Roy began to recruit cohorts to transform Heartworms into a more substantial project. Into the fold came Chris Norborg, bassist for Ted Leo-led garage mods Chisel, and multi-instrumentalist Christopher Porter from Belmondo, Sabine and Veronica Lake.

“Trish and I had met Chris Norborg when he was selling t-shirts for Edsel, when Edsel was touring with Velocity Girl,” remembers Moore. “We hit it off really well and decided to play some music. At the time, I had never even heard Chisel, though I knew their name and was friends with their drummer John Dugan [who briefly played drums in Edsel].”

“Oddly, Trish and Archie asked me to play drums, of all things. I wasn’t much of a drummer,” admits Norborg, “But it was fun.”

Says Moore, “I had met Christopher Porter a few years earlier at the D.C. Lotsa Pop Losers festival, when he was doing a fanzine called Emily’s Hip Pocket; he later released the second Black Tambourine single. Also, he had been in a great band called Veronica Lake, which occasionally featured Pam [Berry] from Black Tambourine singing. When he moved to D.C. from Michigan, Christopher stayed with us for about a month.”

With the Heartworms lineup solidified, the band needed an outlet for their output. “During Velocity Girl tours,” says Moore, “I had befriended Darla label founders James Agren and Chandra Tobey, before they moved to San Francisco and got the label rolling. Similarly, on an English tour I met a guy named Keith Jenkins, who was also starting a label, Wurlitzer Jukebox. This was long before I had e-mail or a cell phone, and James would call me all the time. He started asking if I would give him some music to release. Keith also asked if we’d give him a song for a flexi split single with a then-unknown band called the Apples In Stereo. For Keith’s label, we hunkered down and recorded a song called ‘Blues for a Heartworm,’ with acoustic guitars.”

By early 1995, the band began to record tracks in earnest, heading into the Oxon Hill basement studio to put together 1995’s debut LP Space Escapade, a dreamy, drifting pop odyssey with its eyes glued to the stars. The album art — borrowed from Les Baxter’s 1958 exotica collection of the same name — hints at the LP’s playfully retro-futuristic vibes, as do the liner notes: “We can close our eyes and dream of the future, wondering whether a starlit planet might soon replace a tropical island, the Riviera, or a distant mountain lodge as the ideal spot for a romantic holiday. Or, with the help of this album, we can drift into the future’s lovemist with Heartworms and make a spaceliner escapade by earthlight, tongue safely fastened in cheek.”

In addition to covers by Blondie, the Beach Boys, and Radiohead, the LP features eight originals running the gamut from glittering mope-pop (“Thanks for the Headache” and “Really, Really, Really Sorry”) to crunchy-sweet stompers shrouded in distortion (“Blues for a Heartworm”) to NASA-level cosmic jams (the hypnotic “Space Escapade,” clocking in at just over seventeen minutes!). “Sleep is Kind” even hints at country rock, with what sounds like a pedal steel guitar weaving through the plaintive, open chord strums.

“I’ve always loved ‘Really, Really, Really Sorry,'” confides Norborg. “What a sad song. My college girlfriend and I moved to D.C. together in 1994. We had some rough times both there and after we left, culminating in a terrible breakup in 2000. By all accounts, she still hates me. That song kind of sums up how I felt pretty consistently during those six years!”

Says Moore: “My brother Kevin was 16 or so at the time, and he was learning to play bass. I taught him how to play Radiohead’s ‘Creep’, because he loved that song, and it was easy enough to figure out the parts. We recorded that one just for fun, with no intention of it ever being heard, [but] we decided to add it to the album so my brother could be on a record, and we tacked on the acoustic ‘Blues for a Heartworm’ as a sort of reprise. We picked two songs, ‘Thanks for the Headache’ and ‘Little Hands of Concrete,’ to be a double A-side single, with handmade cover art, as a 7″ for Darla (their third release, after singles by the Grifters and Superdrag).”

“The album was extremely easy to make,” according to Moore. “In the spirit of Yo La Tengo, Flying Saucer Attack, and the Krautrock I was so enamored of at the time, we decided to record a long formless, instrumental space jam [‘Space Escapade’]. We hit the ‘record’ button on the tape machine, and played one of our drone motifs until we ran out of tape. Aside from ‘Blues for a Heartworm’, I don’t think we had any song lyrics at the time, so Trish and I wrote those on the fly over the next few days, and recorded them. Chris came over the next weekend, and we mixed the entire album (except for the already-finished cover songs) in a marathon session. Like the first Velocity Girl single and the Black Tambourine records, everything was recorded on eight tracks, so there wasn’t much to fuss over during mix time.”

However, not everything went according to plan. “Chris crashed in a spare bedroom, and woke up in near-anaphylactic shock after one of our cats had decided to cuddle with him in his sleep. He was absolutely miserable, with his face swollen and throat constricted.”

Heartworms only released one more LP after Space Escapade, 1998’s During, but their limited output is distinguished by its pop craftsmanship and stylistic diversity. Plus, in true side project fashion, it’s clear that everyone was having a blast, and that shines through on the loose, breezy feel of the tunes. “To me, Heartworms was a recording project — an excuse to get out of the city and spend some time with Archie, Trish and their housemate Craig,” says Norborg. “I remember quite a few relaxing weekend days spent goofing around on the drums and appreciating Archie’s notoriously dry wit. We recorded at least two songs of mine — ‘Little Hands of Concrete’ and another [‘Bent & Broken’] that through some strange series of events found itself on a crowded split 7-inch with Guided by Voices, the Grifters, and Sone.” Chisel, on the other hand, “was more about writing songs and playing as many shows as we could manage.”

Says Moore, “At the time, Heartworms was the most spontaneous music I’d ever made, and in retrospect, the quick and dirty nature of its creation gave it a nice charm. I also love that the Heartworms were part of the early histories of two really great labels. Wurlitzer Jukebox’s next two records featured Stereolab and Broadcast, two of my all-time favorite bands, and Darla is still going strong, as a label and distributor.”