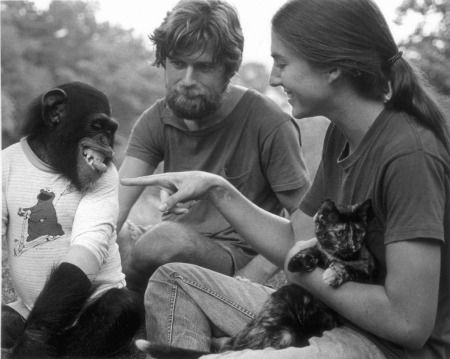

What were they thinking? That question may come up in your own mind multiple times during the first half-hour of Project Nim, as the team of scientists and caretakers involved in trying to teach a chimpanzee named Nim to use sign language in a human fashion, describe their research design. In 1973, Nim was removed from his mother when he was two weeks old and sent to be raised like a human child, in a human family, in a Manhattan brownstone. All jokes about raising a child in the city aside, that seems like just the first and least of the missteps, the larger issue being that no one in Nim’s adopted family had any experience at all with the care of chimpanzees.

What were they thinking? That question may come up in your own mind multiple times during the first half-hour of Project Nim, as the team of scientists and caretakers involved in trying to teach a chimpanzee named Nim to use sign language in a human fashion, describe their research design. In 1973, Nim was removed from his mother when he was two weeks old and sent to be raised like a human child, in a human family, in a Manhattan brownstone. All jokes about raising a child in the city aside, that seems like just the first and least of the missteps, the larger issue being that no one in Nim’s adopted family had any experience at all with the care of chimpanzees.

Neither did anyone in the household know any sign language, the language the study’s director, Herb Terrace, hoped to teach Nim to use. Pile on top of that the fact that the director of the study, Herb Terrace, may have simply chosen the host because he had a prior sexual relationship with Stephanie, Nim’s new surrogate mother, and that Nim was pointedly aggressive around Stephanie’s new husband, and this experiment feels doomed to failure as soon as the the players, interviewed by director James Marsh in present times, start to talk about it.

Project Nim is less about teaching language to chimpanzees as it is about human psychology. Indeed, Marsh doesn’t really even get very deep into the details of the experiment, and how Terrace framed his hypothesis in opposition to linguist Noam Chomsky’s assertion that language was a uniquely human trait — Nim’s full name was, in fact, “Nim Chimpsky”. It’s the scab of decades-old tension between those involved in the experiment and its aftermath that Marsh wants to pick at; and it doesn’t take much prodding before the conflicts and petty human jealousies rise to the top.

Marsh’s previous documentary, Man on Wire, was a tear-inducing inspirational story about the human capacity for going to great lengths to create something beautiful, if ephemeral. Nim may require a handkerchief as well, but for more tragic reasons, as the director digs into darker territory. Namely, the human capacity to go to great lengths to prove a point, no matter what the cost. The cost of the project was the happy life of its subject, shuttled between multiple homes, forced by one man’s arrogance to go entirely against his nature, and eventually ending up in cages along with other lab animals, before a “rescue” that essentially left him in a kind of solitary confinement for half a decade. While it’s apparent that everyone who appears on screen cares about Nim, how that care manifests itself isn’t always in Nim’s best interest.

Marsh’s previous documentary, Man on Wire, was a tear-inducing inspirational story about the human capacity for going to great lengths to create something beautiful, if ephemeral. Nim may require a handkerchief as well, but for more tragic reasons, as the director digs into darker territory. Namely, the human capacity to go to great lengths to prove a point, no matter what the cost. The cost of the project was the happy life of its subject, shuttled between multiple homes, forced by one man’s arrogance to go entirely against his nature, and eventually ending up in cages along with other lab animals, before a “rescue” that essentially left him in a kind of solitary confinement for half a decade. While it’s apparent that everyone who appears on screen cares about Nim, how that care manifests itself isn’t always in Nim’s best interest.

This is what makes the film so compelling, the fact that Marsh is able, much like Errol Morris, to create complex characters and drama simply out of interviews with subjects talking about events from which they are now years removed. No one here is painted with a broad brush, and it’s possible to feel both sympathy and acrimony towards each of them: whether it’s Stephanie for the hippie naïveté that causes her to undermine the project for reasons she believes to be in Nim’s best interest, yet are just as misguided as some of Terrace’s motives, or the animal researcher who is set up as the evil laboratory scientist only to be revealed as something entirely different.

Terrace comes off least sympathetically, and Marsh does nothing to mitigate that perception. He digs his own hole, though, particuarly when he comments with a sleazy grin about how he never really meant for so many of the researchers he hired to be women, it just turned out that way. The movie reveals that he had affairs with at least two of his colleagues, and that grin seems to suggest more.

Nim is a character both central to, and on the periphery of this story, though as the movie goes on, and his own story becomes sadder, the film focuses more on him. The humans battle over his fate, and he becomes something like the sullen child of a broken home, sad-eyed and filled with resentment as his parents yell and bicker in the next room. Or maybe that’s just us placing human emotions on him; the egotism of humans trying to humanize a wild animal is part of what has put him in this situation to begin with, and the film makes us question human behavior not just as we relate to one another, but as we relate to and view other species.

—

Project Nim

Directed by James Marsh

Running time: 93 minutes

Rated PG-13 for some strong language, drug content, thematic elements and disturbing images.

Opens today at E Street Cinema.