There are generally three types of people when it comes to baseball. There are those more concerned with the intangibles, the warm-and-fuzzy nostalgia, the crack of the bat, and the smell of the grass: the romantics. Then there are those obsessed with numbers and statistics, who meticulously score every game and pore over every box score: the nerds. And then there are those who wonder why the hell either of the other two types would want to waste a perfectly nice summer day baking under the hot sun in a stadium with overpriced beer while stepping on peanut shells all day long: the non-believers. In the Venn diagram showing where these three populations converge, there is Moneyball.

There are generally three types of people when it comes to baseball. There are those more concerned with the intangibles, the warm-and-fuzzy nostalgia, the crack of the bat, and the smell of the grass: the romantics. Then there are those obsessed with numbers and statistics, who meticulously score every game and pore over every box score: the nerds. And then there are those who wonder why the hell either of the other two types would want to waste a perfectly nice summer day baking under the hot sun in a stadium with overpriced beer while stepping on peanut shells all day long: the non-believers. In the Venn diagram showing where these three populations converge, there is Moneyball.

That this film has a broad appeal may come as a surprise to those who know the background of Michael Lewis’ 2003 book, on which the script by Steven Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin is based. The book makes the argument that the application of statistical analyses to determine the best group of players to put on the field — specifically, a set of statistical tools known collectively as sabermetrics — are superior to the more subjective methods that have been used for most of the last century by major league scouts. That premise alone might alone be enough to preclude groups 1 and 3 as potential audiences, but the film finds room not only for baseball romanticism, but also for human drama that will draw in even those who don’t know, and don’t care to know, the difference between a safety squeeze and a suicide squeeze.

The film concentrates on one story from the book, that of the 2002 Oakland A’s. As the film opens, the A’s lose the 2001 American League Division Series, and in the post-season, three of their marquee players are picked off by richer teams. General manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt), without the resources to throw cash at talent the way bigger market teams can, needs a new approach to remain competitive. He finds that in Peter Brand (Jonah Hill), a young economist he steals away from the Cleveland Indians to be his assistant general manager, because he believes Brand’s ideas on using statistics to find undervalued players could not only save his team, but also fundamentally change the way people look at the game.

A movie about sabermetric approaches to player selection and staffing on lean budgets ought to be a crushing bore — just start reading through explanations of all the different specialized statistics on the Wikipedia page. But as any grizzled coach in any baseball film would probably tell you, the important things to concentrate on are the fundamentals. Yes, there’s a lot of math and calculation and spreadsheets that went into what Beane did with the 2002 A’s, but the script wisely boils things down to something anyone can appreciate: it’s all about what combination of players is most likely to score you the most runs. And in the midst of doing that, it also becomes a fascinating dual character study: in small scale, of Beane, and in large scale, of the game itself.

A movie about sabermetric approaches to player selection and staffing on lean budgets ought to be a crushing bore — just start reading through explanations of all the different specialized statistics on the Wikipedia page. But as any grizzled coach in any baseball film would probably tell you, the important things to concentrate on are the fundamentals. Yes, there’s a lot of math and calculation and spreadsheets that went into what Beane did with the 2002 A’s, but the script wisely boils things down to something anyone can appreciate: it’s all about what combination of players is most likely to score you the most runs. And in the midst of doing that, it also becomes a fascinating dual character study: in small scale, of Beane, and in large scale, of the game itself.

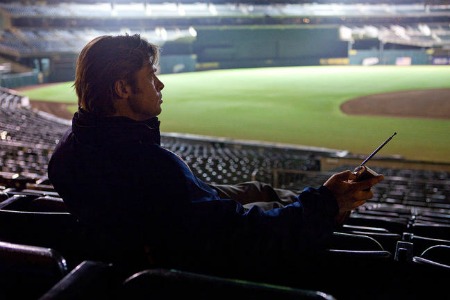

Brad Pitt is an actor of enormous charisma and appeal, but often his finest performances are done behind masks that either obscure or bottle that up: the crazed asylum patient in 12 Monkeys, the violent sociopath of Fight Club, the laconic spiritual fatigue of the title role in The Assassination of Jesse James. In Moneyball, though, Pitt allows himself the nuance and depth of those roles while embracing his pretty-boy magnetism. Beane is a fast-paced salesman of unpopular ideas, and he needs that charisma to sell them, but he’s also saddled with a deep-seated insecurity rooted in his own failure to live up to his promise when he was a player. He’s so tightly wound and focused on what goes on behind the scenes that he can’t even watch the games themselves as they’re happening. That’s a lot to fit into a character who isn’t really allowed to talk about such things, and the way Pitt handles it makes this easily one of the best performances he’s given.

As his polar opposite, Jonah Hill plays Brand as a geeky ball of anxiety, going to places his comedic resume hasn’t really allowed him either. Purists will balk slightly at his characterization: there is no actual Peter Brand, and the real-life figure on which the character is based, Paul DePodesta, is a former athlete himself, and not the chubby misfit shown here. But Sorkin’s contribution to this script is much like what he brought to The Social Network last year: he’s keenly aware of the areas where life fails to create the drama necessary for a narrative, and has no qualms about fudging the facts in service of a great story. The green, unathletic Brand is immediately out of place among the seasoned vets and jockish figures in the clubhouse, and the switch allows director Bennett Miller to easily create visual analogies for how difficult it will be for Beane to get his ideas to fly.

For all the concentration on numbers, the film never loses sight of the fact that this is a game of people, and never gets lost in Brand’s spreadsheets and calculations. Most sports movies use sports analogies to make points about life, but in Moneyball, those relationships go both ways. To talk about what Beane learns from the game, and what he takes from his life and puts back into the game would probably sound trite — which is why it’s so surprising that the film is able to handle it with such entertaining grace.

—

Directed by Bennett Miller

Written by Steven Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin, story by Stan Chervin, from Michael Lewis’ book.

Starring Brad Pitt, Jonah Hill, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Robin Wright

Running time: 133 minutes

Rated PG-13 for some strong language.

Opens today at theaters across the area.