In Red, the question is not “But is it art?” More likely, it’s “But is it art, you little jerk? Now shut up and do what I say!”

Such is the mood of the Mark Rothko seen in Red, currently running at Arena Stage. Rothko, played with seemingly limitless bluster by Edward Gero, is misanthropic, cruel, dismissive, self-consumed and brilliant. Oh, he won’t let anyone forego knowing his brilliance.

Not that you’ll be bothered by the constant reminders. A few minutes into Gero-as-Rothko’s opening inquiry into the soul of Ken (Patrick Andrews), his new assistant, it’s clear that art is Very. Serious. Business.

Rothko’s studio keeps nine-to-five bankers’ hours. “No goddamn old-world salon with lemonade and teacakes,” he promises young, meek Ken, an aspiring painter of his own, though whether the work inspired by his dark personal history is any good, we’ll never know. It’s Mark Rothko’s world, and we should be groveling just to be let in.

But as off-putting as Rothko’s treatment of his new ward is, it’s hard not to be engrossed by Red’s depiction of the artist in his twilight. It’s 1959, and Rothko, trying to preserve abstract expressionism with pop art—Spoiler alert: he’s not a fan—on the rise, has been commissioned to create a series of murals to decorate the new Four Seasons Restaurant at the Seagram Building in Midtown Manhattan.

Red, which walked away from the 2010 Tony Awards with trophy case of statuettes, is the polymath’s dilemma. Rothko isn’t simply the world’s greatest painter (according to Rothko), he’s a Nietzsche- and Freud-spouting, whisky-swilling armchair philosopher who demands nothing short of intellectual obedience from everyone. As the only other person permitted to enter his subterranean studio, Ken will have to suffice to take the full brunt of Rothko’s towering learnedness.

Yet the relationship works, whether it’s master-and-apprentice, teacher-and-student (“I am not your teacher,” Gero barks early on) or perhaps even Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson, though Rothko, after dismissing the comic-book styling of Roy Lichtenstein, would abhor the last appellation. No scene is complete without Rothko dressing down Ken, be it on the failings of his better-loved contemporary Jackson Pollock or the innumerable shades of the title color.

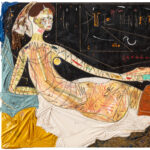

The script, by the playwright and screenwriter John Logan, is full of rants, and, perhaps reflecting Logan’s frequent Hollywood work (Gladiator, The Aviator, Hugo) it moves a bit too quickly at times. But Robert Falls’ direction steadies the pace, allowing us to soak in Todd Rosenthal’s wondrously tangible set, all dusty and rusty, perfect for a painter who says he revels in the absence of natural light. And, while talking luminescence, let us not forget Keith Parham’s lighting job, which manages to make stage replicas of Rothko’s darkest period glow as if you were viewing them at the National Gallery of Art.

If there’s one moment when Red is allowed to speed up, it’s early in the second act. Rothko, finally at a tinge of ease with Ken, allows the young apprentice to graduate from wrapping canvases around frames to assisting in the application of base layers. It’s as close to a sex scene as this show has—Gero applies layers of crimson primer with efficiency and care while Edwards, still learning his techniques, darts about the bottom of the sheet, pushing his brush wherever he can reach. Mozart plays on full blast from the first stroke to the completed job. With the canvas is fully doused, Rothko steps back to inspect his work with a post-climax cigarette. Ken, though, splattered with paint, is splayed on the floor, panting in this achievement. The canvas, now coated the shade of blood, oozes excess fluid. The whole thing feels like some kind of post-coital abattoir.

Despite their different methods of recovering from the orgiastic rush of painting—well, technically the base layer doesn’t count as “painting,” per one of Rothko’s many edicts—Gero and Edwards are well suited. As Rothko, Gero lumbers about in the inconsolable rage that comes from being that much smarter than everyone else. And as the master’s abused assistant, Edwards doesn’t give an inch, only breaking his resolve when he finally conquers Rothko’s brimming ego.

Not that such comeuppance is long-lived. Red is Rothko’s show, after all, and for those not sufficiently reverent for his genius, it’s their own damn fault for not reading Nietzsche.

By John Logan, directed by Robert Falls. About 1 hour 40 minutes. Through March 11 at Arena Stage, 1101 Sixth Street SW. Tickets available at arenastage.org or at (202) 488-3300.