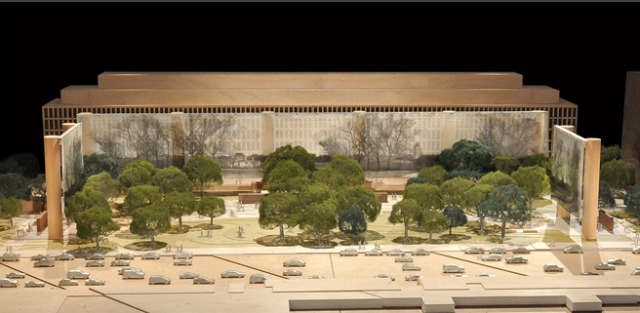

The proposed Eisenhower Memorial, as designed by Frank Gehry.

The proposed Eisenhower Memorial, as designed by Frank Gehry.

There’s been plenty of controversy surrounding the Frank Gehry-designed Eisenhower Memorial, so much so that Eisenhower’s family and Congress have withdrawn everything from their support to funding for it. Memorial-inspired controversy is hardly new to D.C., though, as this is a guest post by Ghosts of D.C. contributor Rick proves. Read the rest of Ghosts of D.C.’s fantastic offerings here.

The Ghosts of D.C. sometimes take shape in the midst of controversy,

although most seem to recede from memory but their remains continue as

companions.

The brouhaha surrounding the design of the Eisenhower memorial may

be viewed by some as a matter of a difference of aesthetic opinions or

one side’s concern for the costs of commemorating an American hero and

president. And no doubt both taste and finance do add fuel to what

seem to be smoldering fires of contention among the various parties to

this, the most recent of a long line of controversies that seem to

bedevil efforts to celebrate someone from America’s past.

Consider the sad story of the Washington Monument for a start.

Congress had planned for a monument to His Excellency as early as 1783

and went so far as to call for it to be an equestrian statue. In fact,

the plans for the new capitol included designation of a site.

But in what would become a rather sobering and repeated spectacle

involving monuments, Congress would not come up with the funds needed

to erect a monument and the society set up to raise funds fell prey to

politics. As a result, the monument was not even started until 1848

and then halted in 1856, still incomplete.

Work on the monument began again in 1876 and it was dedicated in

1885. So there you have it: Washington, THE founding father, dies in

1799, but nearly a century passed before a monument to him was

completed. That, alas, seems to have set, if not a precedent, a

pattern that continues to today.

The Jefferson Memorial did not avoid replicating the pattern.

Championed by FDR, it aroused controversy first by being constructed

just before and during World War II.

Then, no less a luminary than architect Frank Lloyd Wright

criticized the design as too classical, modeled as it was on the

Pantheon.

Historical sticklers opposed the site of the Memorial on the

grounds (pun intended) that no provision had been made in the original

design for the District.

But perhaps the most vocal and demonstrable opponents of the

Jefferson Memorial were citizens, mostly women, of Washington who

protested the removal of Japanese cherry trees to make way for

construction. So irate where they, that they chained themselves to the

trees.

And then there was the Vietnam War Memorial. As divided as

Americans seem to be by that war, it may have been inevitable that

memorializing it, especially so soon after what many saw as its

ignominious end in 1975, would arouse heated passions regardless of

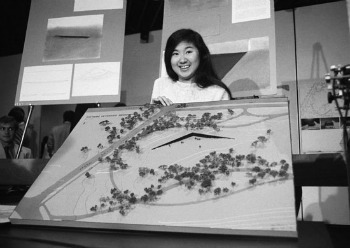

its design. But the design, proposed by a 20 year-old artist, Maya

Lin, was for its time a departure from the typical representational

but usually heroic depiction of most war memorials.

Opponents, including Ross Perot who provided funding for the

competition to select a design, were appalled and described it as “a

scar in the earth” and the “black gash of shame.”

Even after its installation, the Memorial aroused opposition and

demands for something more conventional. As a result, statues of

troops were erected nearby in 1984 and again in 1993 when the figures

of three women and a wounded man were added.

Today, of course, the Vietnam War Memorial (which was never a

declared war) attracts huge numbers of visitors year-round, and

non-representational design has become part of several memorials.

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle