Photo by Eggert Jonsson via Kennedy Center

Photo by Eggert Jonsson via Kennedy Center

Metamorphosis, a poignant adaptation of Franz Kafka’s darkly comic fable about a man’s overnight transformation into “a monstrous verminous bug,” closes tonight at the Kennedy Center after an all-too-brief three-day run, part of the “Nordic Cool 2013” programming, which presents artistic works from across Scandinavia through next month.

Iceland’s Vesturport Theatre Company, in collaboration with the United Kingdom’s Lyric Hammersmith, performs the piece in English to include a lot of Kafka’s morbidly funny language: “Yes, let’s talk about money,” says the mother at one point. “It’ll take my mind off everything.”

But words are secondary in this arresting physical rendering, emphasized as an allegory about the rise of fascism in Europe.

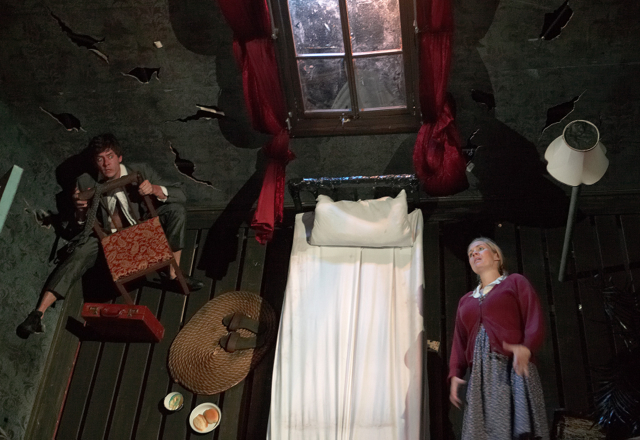

The show begins in the Samsa family’s modest kitchen, around a dining room table with four chairs. Three of those chairs are occupied, by the home’s patriarch Herman (Ingvar E. Sigurdsson), matriarch Lucy (Edda Arnljotsdottir) and their daughter Greta (Selma Bjornsdottir).

In a lovely series of personality-conveying dance vignettes, each member of this nuclear unit has his or her own movement monologue, gliding around the room. Even putting sugar in the bowl is a dance step of sorts.

But where is occupant of the fourth chair?

Well, Gregor (Gísli Örn Garðarsson) is upstairs, coming to terms with the fact that his fitful night of bad dreams has opened up into an even bigger real-life nightmare: he is now a giant cockroach (a premise that adds just the right element of ridiculousness to an otherwise fairly accurate, if embellished, domestic drama).

The first glimpse we get of him is that of a glowing, scarab-like silhouette, through the sheets of the upstairs bed, which acts as a shadow curtain.

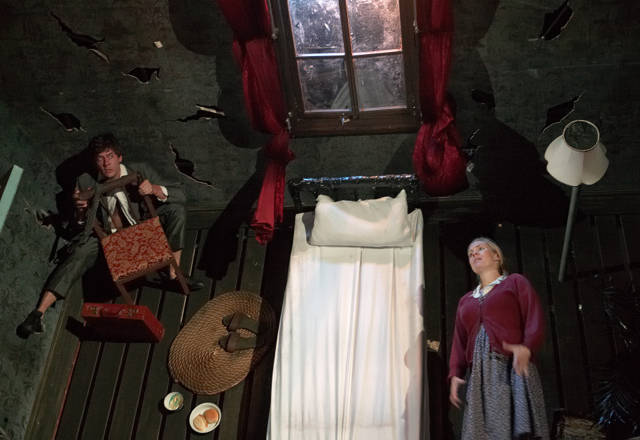

This is a show that builds upon itself layer upon visual layer. When the lights come up fully on Gregor’s bedroom, after that initial hint, your heart stops for a moment when you realize that the entire layout is actually perpendicular to the kitchen downstairs.

It’s a cubist painting of a room, around which Garðarsson, a founding member of Vesturport and co-adaptor of the material, moves as if he’s not subject to gravity.

Omitting the bug costume was a laudable choice. Gregor wears a normal suit but his movements are increasingly buggy. (He practically chases his disgusted father down the staircase, using all four limbs to scuttle down the bannister.)

It’s hard to imagine the kind of endurance and strength that playing Gregor requires, but Gardarsson is so precisely controlled that you can simply let your imagination go. The ever-changeable set, which employs a trampoline, hidden trap doors, Velcro and a Spanish web, is a fittingly dynamic playground for Gardarsson’s talents.

As an actor, Gardarsson also manages to capture the right emotional tenor to Gregor—that of sorrowful confusion at his own family’s increasingly hostile attitude toward him.

There is a disconnect, of course, between what we hear Gregor communicating, and what his family communicates. As he tries to reassure them or express affection toward them, they clap their hands over their ears and slap him away, complaining of a weird clicking noise.

It’s the duality of how they perceive him and how he comes across to us, the omniscient audience, that makes this a powerful story about intolerance.

It’s not just a story about Gregor, of course. His sister, Greta, who begins as an ally to her misunderstood brother—who picks up on things like his new proclivity toward eating rotten food and defends him from the wrath of their father–is eventually changed by her newfound power.

Her transformation into a young woman happens very deliberately, and coincides with a darker migration toward control and intolerance. The entire family’s nasty and abusive behavior toward Gregor’s pest-like presence plays out in increasingly militaristic movements.

Echoes of Nazi Germany are at their pinnacle during a visit from a character called Herr Fischer (Vikingur Kristjansson), a potential lodger/source of income and, we’re led to believe, a possible suitor for Greta.

Herr Fischer is a boorish man who prefers to talk about shooting his gun over listening to Greta play the violin; who woos a young woman by praising her “devotion to duty.”

In a chillingly direct line, he also speaks of the importance of eradiating the “vermin from society,” while we see Gregor languishing upstairs, weakened by starvation and beatings, cloaked in a greenish-blue light that contrasts the warm glow downstairs.

Backed by a simple, thoughtful musical score by Warren Ellis and Nick Cave (yeah, that Nick Cave) that intermingles violin, piano, and finally Cave’s deep, melancholy voice, this production shows us all that theater can do in its final portrait of twisted spring.