Via Shutterstock

Via Shutterstock

Two hearing-impaired women are suing the D.C. Housing Authority, claiming the agency continuously denied them access to an interpreter, which they say led to them suffering repeated “embarrassment” and “humiliation” when attempting to participate in housing programs.

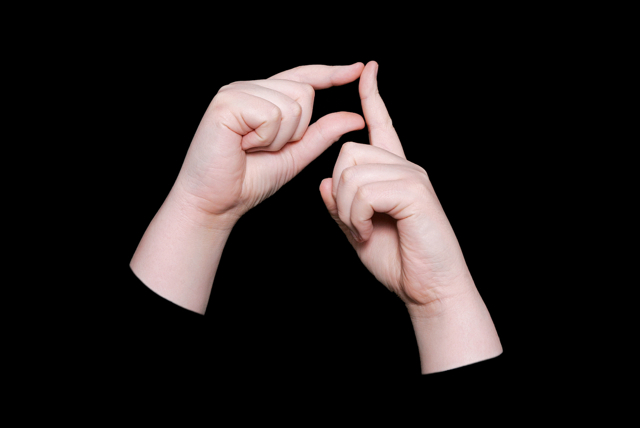

The plaintiffs, Jacqueline Young and Latheda Wilson, both state in their complaint, filed yesterday in U.S. District Court, that while American Sign Language is their primary language, DCHA employees routinely failed to provide an interpreter. Instead, the suit alleges, the agency resorted to hastily scribbled notes, attempted lip reading, and other ineffective gestures in attempting to communicate with the plaintiffs.

Young and Wilson are enrolled in DCHA’s housing choice voucher program, which provides rental assistance averaging about 70 percent on qualifying apartments and houses. But as a result of the alleged treatment at the hands of DCHA, Young and Wilson state they have been unable to deal with “deteriorating conditions” in their current domiciles.

In spring 2012, the complaint reads, Wilson’s apartment had deteriorated into a hive of rodents, insects, and mold. The plumbing was failing, and efforts to get her landlord to make the necessary repairs went in vain. Wilson found a better apartment, but when she attempted to have her voucher transfered to the new address, but without an interpreter, she was unable to communicate with DCHA employees.

Wilson’s interpreter-free attempts to make her case to switch her voucher, the suit alleges, were met with rather disparaging treatment. “DCHA staff in the reception area exhibited impatience and contempt toward Ms. Wilson when she attempted to communicate without the interpreter essential to effective communication,” the suit reads

The housing authority never responded to Wilson’s request to move, and she still resides at the infested apartment on upper Georgia Avenue NW.

“The law is very clear on this issue,” says Megan Cacace, an associate at Relman, Dane, & Colfax PLLC who is representing Wilson and Young. Cacace says DCHA is in violation of the Fair Housing Act and the Americans With Disabilities Act, the 1990 landmark legislation that prohibits discrimination on the basis of physical or mental impairment.

Young enrolled in the housing voucher program in 2006, and Wilson in 2011. During her time in the program, Young has had access to a sign language interpreter at DCHA just once, Cacace says, and that was only after she contacted an attorney. Both plaintiffs have been made to sit through several presentations and meetings without the ability to understand what the program’s supervisors are saying.

“They are expecting them to communicate through notes and gestures,” Cacace says. “Having them sit through important presentations without anyway of understanding what is going on. It’s like treating someone with a child and expecting them to deal with it.”

People receiving housing vouchers are expected to follow many regulations, but without having those guidelines interpreted for them, the lawsuit states that Young and Wilson have both come away feeling confused about the program and fearful of running aground of the rules.

The complaint goes on to read that DCHA systematically disservices its enrollees who are hard of hearing:

People with hearing lossseeking interpreter services in order to access the DCHA’s programs are often given the run-around, advised that no interpreters are available, forced to have appointments and services postponed substantially, denied the benefit of interpreters during meetings, or promised interpreters when none are ultimately provided.

Based on information we have there appears to be a consistent pattern of violation of the rights of people with hearing impairments,” Cacace says.

DCHA states on its website that it accommodates disabled applicants in accordance with the Americans With Disabilities Act, including sign language interpreters for people with hearing loss.

But Young and Wilson’s suit suggests a much different reality. It states that Young has been left in waiting rooms for hours after requesting an interpreter, only to wind up wasting her time and being told that she missed her appointments when DCHA’s office closed for the day. Young has also been attempting to move from a two-bedroom apartment to a three-bedroom unit so that she can live with her son, but the lack of proper communications has impeded that.

Young and Wilson are asking for unspecified compensatory and punitive damages, as well as guarantees that DCHA will perform in accordance with the ADA.

“The equal rights of people disabilities is an important civil rights issues,” Cacace, their lawyer, says. “This lawsuit is taking to vindicate those rights. This isn’t anything new.”