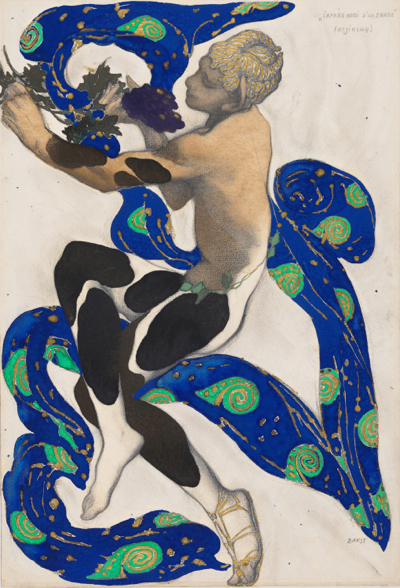

Leon Bakst’s costume design for Vaslav Nijinsky as the Faun from The Afternoon of a Faun, 1912 (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

Leon Bakst’s costume design for Vaslav Nijinsky as the Faun from The Afternoon of a Faun, 1912 (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)By Julia Langley

Most art exhibitions are of a type. They are designed to introduce the viewer to the history and development of a certain artist or group of artists or style of art. Paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, and other media are shown in a generally chronological order to guide the visitor towards a deeper understanding of the subject at hand. It is a simple formula and usually works.

Something different is afoot at the National Gallery of Art, and it is clear just a few steps into Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes 1909-1920: When Art Danced With Music, which opens Sunday. The generally hushed halls are alive with color, light, movement, and sound. Each exhibition room is a set, making visitors feel as though they have snuck backstage to peek at the costumes, scenery, posters, drawings and other elements that make a production possible—but not just any old production.

Serge Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes, challenged traditional ideas of art, dance, music and theater. He brought together artists, dancers, musicians, set designers, costume designers and choreographers to created unified artworks that shocked early 20th-century audiences and changed the course of dance.

The Ballets Russes began after the Russian Revolution of 1905. Russia was becoming ever more dependent on France for loans and wanted to maintain positive ties. Diaghilev, an arts promoter who had mounted a successful exhibition of Russian historical portraiture attended by Czar Nicholas II, found support for his idea of taking Russian culture to Paris where he created productions of Russian painting, opera, and music. In 1909, when he lost funding for his opera season, he decided to showcase Russian dance. Diaghilev hired a troupe of dancers on summer break from the Imperial Ballet to dance a new repertoire created by a young choreographer named Mikhail Fokine. The athletic vitality of Vaslav Nijinsky and the ethereal beauty of Anna Pavlova dazzled Parisians.

Over the next decade, Diaghilev brought together the greatest avant garde talents in music, art and dance to create what Richard Wagner had earlier termed a gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. Diaghilev’s collaborators included the visual artists Leon Bakst, Jean Cocteau, Giorgio de Chirico, Sonia Delaunay, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Georges Roualt, and the composers Igor Stravinsky, Erik Satie and Sergei Prokofiev. Diaghilev’s dancers and choreographers included Mikhail Fokine, Vaslav Nijinsky, Leonide Massine, Bronislava Nijinska and George Balanchine. Each artist was given the freedom to work in his or her own style and encouraged to collaborate.

The creative force unleashed by Diaghilev is overwhelming. Throughout the National Gallery of Art’s exhibit, video clips from recreations of Ballet Russes productions including Afternoon of the Faun, The Rite of Spring, The Firebird, and The Prodigal Son show how seamlessly the individual talents of Diaghilev’s cutting-edge collaborators blended together onstage. In the original Firebird, for example, ballerina Tamara Karsavina presented Michel Fokine’s choreography based on Russian folk tales to music by Igor Stravinsky in a costume created by Leon Bakst. Natalia Goncharova’s original, 52-feet-by-34-feet backdrop for The Firebird is so large, the ceiling of the hall displaying it needed to be raised so it could fit inside.

Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes 1909-1920: When Art Danced With Music opens Sunday through Sept. 2 at the National Gallery of Art East Building.