When I met Elijah, he was sound asleep.

I’d been driving down a rural highway, exploring the towns and villages around the now abandoned Springs Recreation Park in Lancaster, S.C. Off to the right, at the top of a steep hill, I caught a glimpse of an abandoned building and slowed down for a better look.

Some ruins are nearly unidentifiable even when they’re intact. Warehouses, office buildings and workshops are defined by their tenants, not their lines. But there’s no mistaking an elementary school, even years after the teachers and kids are gone.

There’s the asphalt semi-circle, once full of cars and school buses. The long, single-level brick facade, the yellowing shades in fold-down windows. The arched roofline of its gymnasium. The baseball backstop and overgrown basketball court. There was no sign here, but I knew this place had been a grade school.

In front of it, slumped in a lawn chair, was an old man in dirty blue coveralls, He was fast asleep, his head tilted awkwardly to the side, his arms resting on his lap with a single outstretched palm full of seeds.

“Excuse me,” I said, and when that drew no response I put my hand on his shoulder and felt a strange, unexpected sort of intimacy.

Years ago, in college, I’d fallen asleep in a Greyhound station in Memphis, Tenn. and awoke to the feeling of a man touching my hair. I opened my eyes and immediately realized that he was trying to cut off a lock of it.

What struck me the most was the expression his face when I woke up — one of indignation, as if to suggest that he had every right to do what he was doing, and that my instinct to pull away was something to be ashamed of.

The old man in the chair responded much the same way: “What the hell are you doing?”

What could I say? I suddenly felt like a moron who had pulled his car onto someone’s front lawn, strolled right up to him, and nudged him out of his sleep, just to take pictures of the inside of his house. I thought of fleeing, but the old man asked me to stay. He had dozed off while tending to his garden, a narrow patch of dry soil to his left which he’d dotted with okra seeds. I offered him my hand, and he took it, introducing himself as Elijah. Slowly, he rose from his chair and pulled over another for me. I sat. We talked.

“I’ve been here going on eleven years,” he said. He spoke slowly, laboriously. “Let me show you what it was like when I got here.” He went inside and came back with a banker’s bag, from which he pulled an old Polaroid photo. It was him, all but unrecognizable, nattily dressed in a suit, bow tie and fez, easily identifiable as a member of the Nation of Islam. The lawn he stood on was freshly cut, the school behind him in decent shape.

“I came here to fix the place up,” he said. “I wanted to make a home for the old folks. But no one wanted to help.”

I wasn’t surprised that he had failed. Between Springs Park and Great Falls was some of the worst poverty I’d ever seen. This wasn’t a place where people could afford philanthropy. Most were just happy to survive.

To my surprise, he invited me into the school. I offered him $40 to let me take photos of the building, which he refused. I had told him I was most interested in the gym, and he led me down the hall to it. I could barely breathe. The smell of urine and excrement was overpowering.

The school had long been stripped of all of its fixtures, and over the years Elijah had filled it with junk. The gym, though, was beautiful. Six basketball goals — the kind that retract towards the ceiling — over a stunning parquet floor. On a stage at the far end of the gymnasium were twenty or thirty desks, covered with the engravings of the students who sat at them. I ran my fingers along a set of initials and longed to add my own name to the mix, to feel the rush of juvenile delinquency once more.

I snapped some pictures in Elijah’s home. Among them, a shot of some World Book encyclopedias on a shelf in an adjacent room. I glanced at the “S” volume, immediately remembering (rather shamefully) how many hours I spent as a youth studying the entry for “sex”.

The World Book. Photo by Pablo Maurer

Elijah seemed to relish the chance to talk.

He spoke at length about his mistrust of white people. What started out as “I don’t have any problem with whites. The lady next door who looks in on me is white, we get along just fine” evolved into stories of the absolute horror of being a black man in South Carolina well before the civil rights movement. This was a person who’d lived a good portion of his life during a time when getting lynched was a real possibility. It was gut-wrenching to listen to but I felt grateful to even get a window in on that experience.

Afterwards, he peered at the screen on the back of my camera and examined my photos of the school, then surprised me with a question.

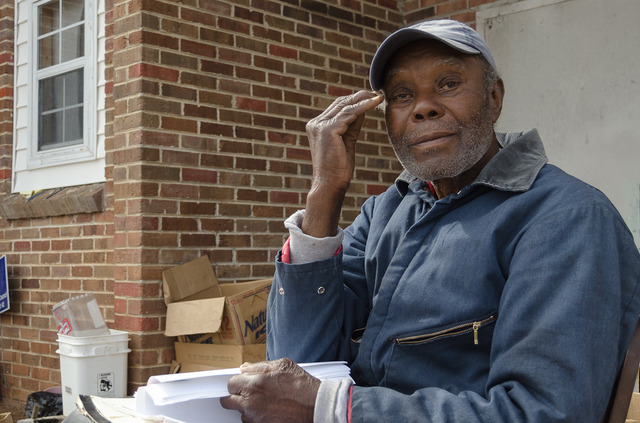

“I suppose you wouldn’t want to take a photo of me?”

I had him sit in a chair by his garden. I sat across from him, raised my camera and studied him through my viewfinder. A warm smile came over his face, and it filled me with joy. Though well into his seventies, his face seemed to me to be a lot younger than my own.

I couldn’t help but chuckle at his expression and it must have embarrassed him. His smile disappeared.

From the banker’s bag came a photocopy of a magazine cover from the ’70s: “Accomplishments of the Muslims”. On it was a photograph of former Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad, to whom this man shared a striking resemblance. He held it up to his face, and I took a few more photos.

Elijah asked for my address, which I gave him. He also gave me the address and phone number of the family who lived next door to him and asked me politely if I wouldn’t mind sending them the photograph I’d just taken, suggesting that they pass it along to him.

“Yes,” I told him, “I’ll be happy to.”

I collected my things, got in my car and headed toward Columbia, S.C. A couple of hours later, as I turned off the road into a parking lot, I was broadsided by an SUV going about 50 miles per hour. My car was totaled and I sold it to the tow truck driver who hauled it away.

That night I found myself riding a Greyhound bus from Columbia back to my hotel in Charleston. It was probably the first time I’d done so since the day that stranger roused me from my slumber in Memphis.

Only weeks later, when I went to send Elijah his photo, did I realize that I’d left his address in the car I’d sent to the scrap heap.