Via Library of Congress.

Via Library of Congress.As the 29th President of the United States, Warren Harding’s time in office was short lived. He died in the third year of his Presidency. His short time in office was also marred by numerous political scandals within his administration, including the appointment of the “Ohio gang,” the Teapot Dome scandal and his reputation as a heavy drinker, to name a few.

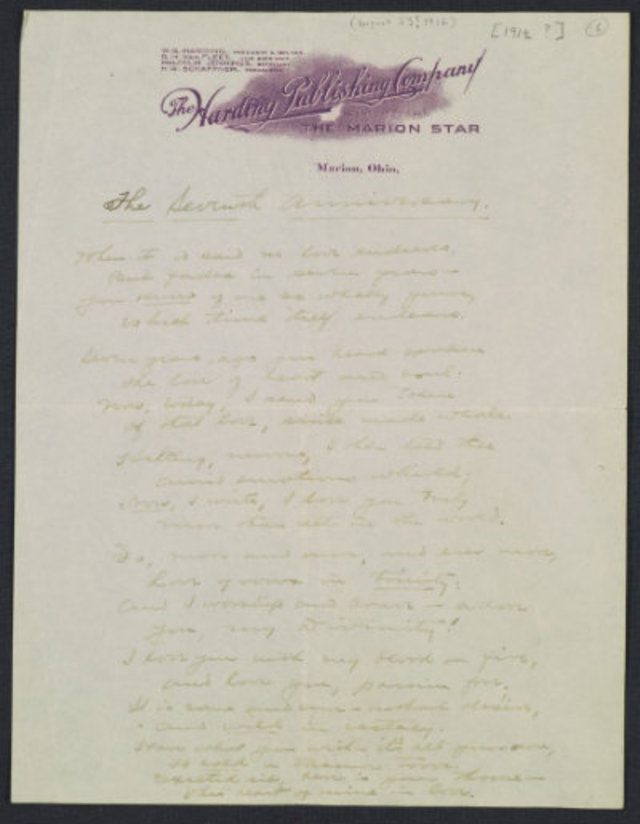

Today, the Library of Congress released approximately 1,000 pages of correspondence between Harding and his longtime mistress, Carrie Fulton Phillips. The love letters are now open to the public for the first time ever—viewable on the Library of Congress’s website.

According to the Library of Congress, the letters “sheds light on a man in love on the eve of his presidency and a country on the brink of World War I.” The Library says that Harding and Phillips had a secret romantic relationship from 1905 to at least 1920, but that a lot of the letters aren’t dated. Of the content of the letters, the Library writes that they’re “at times deeply passionate, but there is more to the collection than love notes and sentimental poetry.” They also “give travel and speaking engagement information on Harding,” along with the intricate plans made to meet with each other.

So how did the letters come into possession of the Library of Congress and why are they just now available to the public? When Phillips died in her home in Ohio, it was discovered by a court-appointed lawyer that she had kept all the correspondence between her and Harding hidden. That lawyer made the collection available to an author who was researching Harding for a biographer in 1963, however, Harding’s nephew—Dr. George Harding—found out about the letters and sued to keep them away from the biographer. Eventually, Harding’s nephew purchased the letters from Phillips’ heirs and donated them to the Library of Congress, “with the stipulation that the Library keep the papers closed until July 29, 2014—50 years from the day the Ohio judge first closed them.”

The Library says they also “recently obtained additional material from the Phillips/Mathée family,” which give more context to Harding and Phillips’ relationship and the letters. You can view them here.