Photo by Clif Burns.

Photo by Clif Burns.

By DCist Contributor Victoria Finkle

D.C. is an expensive place to live, and feeding yourself is no exception. Follow Capital Cheapskate each month for a look at the cost side of the ledger, and for tips to enjoy the city’s burgeoning dining scene without breaking the bank.

Confession: I’ve mentioned the growth of the city’s restaurant scene several times since launching this column. But it wasn’t until earlier this month that I realized I couldn’t tell you what that actually means.

Sure, I had some anecdotal evidence. Like many of you, I’ve circumvented the seemingly endless number of construction barricades on 14th Street. And I’ve seen the press about this or that fancy chef who’s finally deigned to open up shop in the district.

That’s all well and good, but it doesn’t give us a sense for the bigger picture—the scope of the growth. It also doesn’t shed any light on what the transformation has meant for those in the industry or for diners. So that’s what I’ve tried to lay out below, at least in broad strokes.

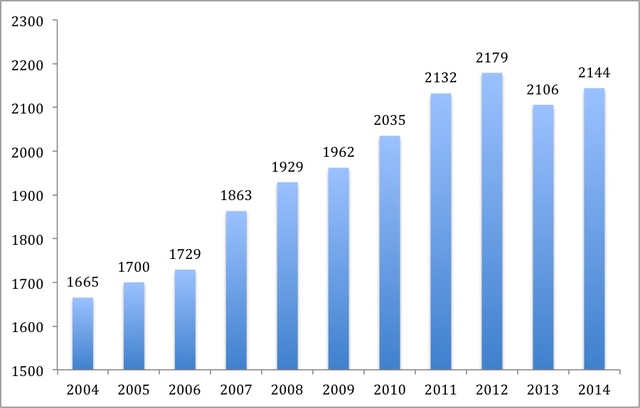

I started my investigation with a trip to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The city was home to 2,144 private “food services and drinking places” in 2014, up from 1,665 establishments a decade ago. By that measure, the industry has grown about 29 percent over the past decade.

As you can see below, the number of restaurants actually peaked in 2012 at 2,179, though the overall trend remains an upward one.

Source: BLS. Graph by Victoria Finkle.

Source: BLS. Graph by Victoria Finkle.

For some additional context, I jumped into the Wayback Machine for a historical look at the industry. It turns out that the National Restaurant Association projected the city’s dining scene would take in $1.8 billion in sales in 2005 (about $2.2 billion in today’s dollars). Restaurants also employed nearly 42,000 workers. The group estimated at the time that D.C.’s dining industry would cut checks for more than 45,000 workers by 2015—a rather modest guess, it turns out, even coming out of the economic crisis and recession.

Jon Arroyo, beverage director for Farmers Restaurant Group, remembers coming to D.C. for the opening of Founding Farmers, on the cusp of the city’s culinary awakening.

“I was new to the city and it was a regime change. President Obama was coming into office and there was a lot of different energy in D.C. I literally got to experience the shift from steakhouses and cigars, if you will,” he said. “Fast forward seven years and it’s out of control, it’s booming.”

The district’s dining scene is now set to bring in $2.8 billion in sales this year, a 27 percent boost over the past decade. More than 60,000 people now work in food service, which accounts for about 8 percent of the city’s workforce.

The Restaurant Association of Metropolitan Washington added about 300 members between 2012 and 2014, the fastest period of growth in its 95-year history, a spokeswoman told me.

By comparison, D.C.’s total population has risen about 16 percent over the past decade—impressive growth, though it hasn’t kept pace with the dining industry. Put another way, in 2004, there was a local restaurant for every 341 people in the district. Now there’s one for every 307 people.

Lucky for restaurateurs and other retailers, the lion’s share of the population growth has been young people in their 20s and early 30s, many with time on their hands and money to burn.

“D.C. is becoming America’s media and intellectual capital in some ways,” said Tyler Cowen, an economics professor at George Mason University. He described the city’s growth as “explosive”—thanks in part to the rise of “young people, ‘cool’ people, not just interns.” (Ugh, those interns.)

Remember when Forbes, the ultimate arbiter of hip, ranked D.C. as the coolest city to live last year? OK, so maybe not everybody jumped on that bandwagon, but it’s hard to argue D.C. isn’t having a moment. We have a baseball team that isn’t terrible, the music and tech scenes are on the rise, and there’s a lot of excitement about the direction the city is taking. The snake people also want fresh, exciting places to eat.

The city’s burgeoning hipness has also come at a time when the broader culture around dining is being upended.

“When I started, there was no Food Network, not one person could name a chef by name,” said Tom Meyer, president of Clyde’s Restaurant Group, who went to culinary school in 1978. “Now you go to any city and people can name five chefs in the town.”

Across the country, the restaurant industry has expanded dramatically over the past decade, with sales of over $709 billion expected this year. That’s up 22 percent from a decade ago. The south and west—states like Texas, Florida and Arizona—are poised to see some of the biggest gains in sales and employment in coming years.

The question now is, what do all of these changes mean for diners?

Well, to be sure, things aren’t perfect. Critics say the city still lacks a cohesive “food identity” and remains a second or third-tier restaurant town, at best. The dining boom has also come hand-in-hand with rapid gentrification across the city, and it’s impossible to talk about the explosive growth of a younger, whiter, wealthier D.C. without acknowledging the loss and displacement of older residents. Expensive real estate makes it difficult to find affordable housing and drives up prices at restaurants and other businesses, too.

Moreover, advocates say food service workers remain chronically underpaid, and the brewing fight over a $15-per-hour minimum wage, including for those in the restaurant industry, is likely to be a contentious one.

That said, the biggest boon for everyday diners is likely the added variety and diversity of available options across many parts of the city. Even more than an increase in the number of restaurants, there’s been a surge in the type and quality of offerings available.

“The growth has made the dining scene more exciting and the buzz begets more business,” said the RAMW spokeswoman. “Now diners, instead of necessarily identifying one restaurant for their dinner plans, will instead go to a neighborhood rich with restaurant options—like 14th Street, Capitol Hill, Penn Quarter—and know that they have so many options for bars and restaurants to pick from once they get there.”

Meyer notes that diners have also become more daring in their food choices, which in turn gives chefs more creative freedom.

“The customers are way more adventurous than they used to be,” he said, pointing, for example, to the popularity of an octopus bolognese special recently offered at The Hamilton.

“Ten years ago, forget it, that would have been laughable. Now, people are willing, but it’s got to be good,” he added.

That openness likely makes careers in food more enticing overall and D.C. a more attractive place for those at the top of their profession—a virtuous circle.

You’ll find long wait times at places in some of the hottest neighborhoods, like H Street NE and Shaw, but the vast industry growth means there are usually other, less oversubscribed options nearby.

“There are more popular places, and thus some longer wait times, but there are also more places with no wait times at all, so overall I take this to be a positive,” Cowen said.

For the restaurants, this means there’s more competition, which forces restaurateurs to up their game to stay in business. Annual figures disguise the bumps and dips occurring every day in the industry. Nearly 80 restaurants opened in the D.C. area this spring alone, while others shuttered their doors.

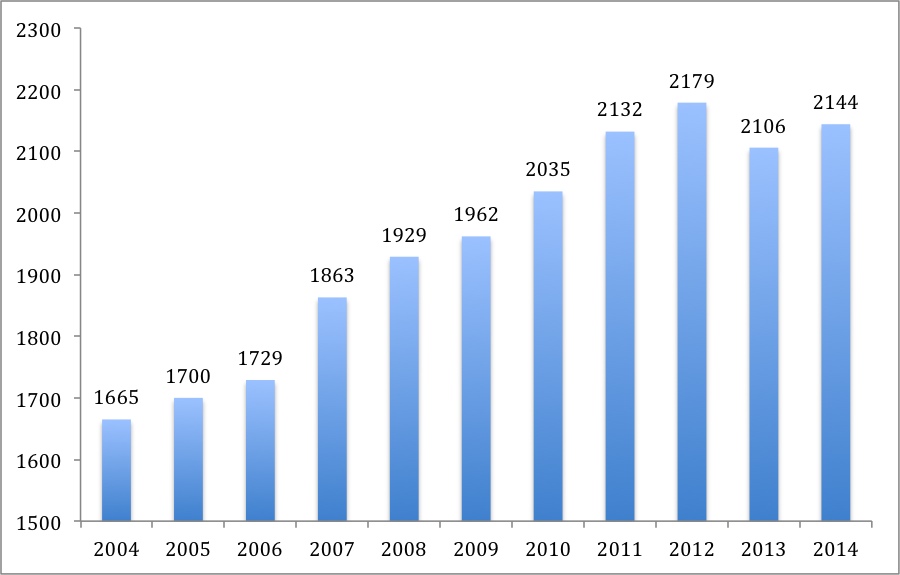

Below I’ve graphed the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ quarterly data for “food and drinking establishments”—instead of the annual stats—over the past three years. This is not a static environment!

Source: BLS. Graph by Victoria Finkle.

Source: BLS. Graph by Victoria Finkle.

That churning arguably leads to better quality food and even spruced up settings as diners vote with their feet. It may also put at least some downward pressure on prices, even as owners contend with expensive real estate, rising food costs and the need to keep the best workers from being poached.

“The more restaurants open up, we have to do our job better—it forces us to be attentive and to look in the mirror and try to do better than we did yesterday,” said Arroyo.

“People understand they can eat well and drink well and don’t have to get hit over the head with the price attached to that.”