The Lawnmower Man ushers me through the labyrinth of the Longworth House Office Building with the expertise of a longtime Hill staffer.

Up two sets of stairs, around a couple of corners and we arrive at a long corridor of offices. Unfazed, he turns straight to the first suite. “See that flag? That’s a POW flag,” he tells me, pointing to a black and white banner hanging next to the entryway. “That’s a good sign,” he says, a little conspiratorially, before opening the heavy wooden door and heading inside.

The Lawnmower Man is here at the House on a mission, as he has been for just about every weekday for the past year and half. He is here to convince our representatives in Congress that America’s national parks and memorials should stay open in the event of another government shutdown. It’s a subject he knows well.

After all, it fell to him, rather unexpectedly, to take out the trash and mow the lawn and clear the branches of the nation’s front yard in the fall of 2013.

Chris Cox, a chainsaw artist from Charleston, became an unlikely folk hero that autumn. With shaggy curls hanging in front of his face and a South Carolina flag at his side, Cox captured a weary country’s attention after he was spotted pushing a lawn mower in front of the Lincoln Memorial. He became the Lawnmower Man.

As Congress dithered, news outlets rushed to cover the story of the mysterious bearded guy doing pro bono yard work on the Mall. Someone started a ‘Lawn Mower Guy For Congress‘ Facebook group, thousands of people sent messages of support, and fans contributed to a crowdfunding campaign for him. Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA) went over to the Mall himself to interview the man.

Cox was floored by the attention. When he first went down to the Mall—initially with the goal of protecting the monuments from possible vandals—he brought a football to toss with other people who had the same idea. Cox quickly realized there wasn’t anyone to catch it; he was alone in his mission.

The third day on the scene, the garbage cans started overflowing in front of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. So he went to the store and got some trash bags. As Cox tells it, he just planned on clearing up that one area. “Several hundred trash cans later, the grass got tall, which led to one thing after another,” he says of the ensuing work. After news of his cleanup went viral, a small army of volunteers from around the country joined him. He merrily named the group the “Memorial Militia.”

After sixteen days, Congress came to an agreement. Park Service employees returned to taking out the trash and mowing the lawn and clearing the branches. Members of the militia went back to their regular lives.

Mayor Vincent Gray’s office estimated that the D.C. region had lost $400 million in economic activity each week of the shutdown. And with the closure of the city’s main tourist attractions, much of that could be traced to a steep drop in visitor spending. Hotel bookings in D.C. alone declined by $2 million.

But the damages were hardly restricted to Washington. National parks around the country saw 7.88 million fewer visitors in October, and nearby communities lost out on an estimated $414 million in tourist spending. Some even argued that national parks—both in D.C. and elsewhere—were the scene of the shutdown’s biggest battleground.

Indeed, one of the most unforgettable scenes that October was a group of WWII veterans “storming” past the barricades to the monument dedicated to their service.

No sign of folks leaving. The vets have control of the memorial. #shutdown pic.twitter.com/eGj4kmFEiP

— Leo Shane III (@LeoShane) October 1, 2013

To a dismayed Cox, this was the worst consequence of the shutdown.

Aging and ailing veterans from around the country had planned trips to D.C. months in advance. For many, this was their last or only chance to see those hallowed spaces—and Congress ruined it.

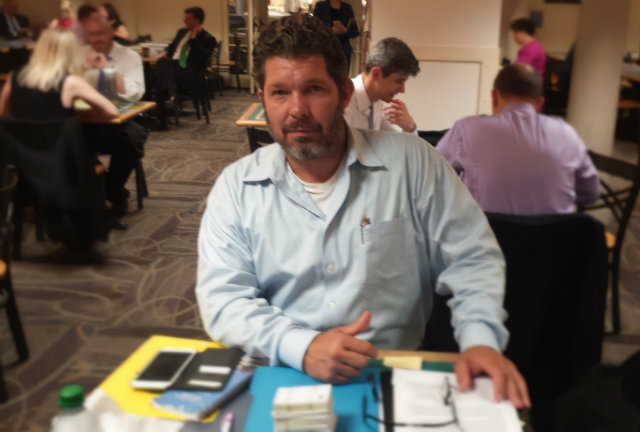

“When they get to town to see the World War II Memorial and it’s shut down for no other reason than political expediency, then something’s wrong,” Cox said recently at the bustling cafeteria in the bowels of the Longworth building. “That’s the goal here, to see that that never happens again.”

And so just as he once spent day after day pacing the National Mall, picking up cigarette butts and taking out the trash, now he paces the halls of Congress, knocking on doors and talking to staffer after staffer.

The curls have been shorn, the beard lost the scruff, the t-shirt replaced with a blue button-down. There’s nary a rake in sight. You’d never guess he is the Lawnmower Man, in fact, until he starts speaking. Then you’ll hear a familiar slight lisp, and the same seemingly limitless fervor that propelled him to keep the Mall spotless when the government couldn’t.

Chris Cox sits with piles of business cards in the cafeteria of the Longworth House Office Building. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

Chris Cox sits with piles of business cards in the cafeteria of the Longworth House Office Building. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

Just a few days after Issa introduced himself to Cox on the Mall, the California representative recognized the South Carolinian chainsaw artist in the Congressional Record. So that’s who the one-time Mall caretaker turned to later to come up with a way to ensure that vets would never be locked out of the national memorials again.

“Once I approached Congressman Issa, I was fairly confident that [a bill] would be introduced, so I decided to make it full time,” Cox said. While the lawyers and legislators hashed out the details of a proposed law that would allow national parks to stay open in the event of a shutdown, Cox decided to start a one-man lobbying campaign.

He packed up his life in Charleston, shut down his art studio, and moved to Fort Belvoir. From there, he began a daily commute into the District for his new self-appointed gig. Cox learned how the Hill really works in fits and starts—figuring out, for example, that he should still come in even when Congress wasn’t in session—and honing his elevator pitch.

Fifteen months after he began, H.R. 1836 was introduced, co-sponsored by Issa and D.C.’s Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton. The Monuments Protections Act is intended not only to keep the monuments and memorials open, but all national parkland, forests, and wildlife refuges, during a “lapse in appropriations.” In the event of another shutdown, the bill states, D.C., federally recognized Indian tribes, and U.S. territories would be authorized to fund their operations. Once the federal government reopens, it would reimburse them.

Having a bill with a number on it—and both a Republican and a Democrat’s name on top—has made it much easier for Cox to find listeners on the Hill. With the help of a pocket Congressional guidebook, Cox continues to walk into offices, asking to speak to legislative aides who focus on veterans affairs.

“It’s not hard to align yourself with like-minded people when you’re trying to show support for veterans. And so with that philosophy, I feel like the sky’s the limit for this bill. … My goal is to see that it passes with the most bipartisan support in recent history,” Cox says. And no amount of healthy skepticism is going to deter him. “You can call me naive if you want but it’s not going to slow me down. I’m going to keep knocking on doors until it happens,” he adds.

The effort is coming at a tremendous personal cost. Not realizing that this process would take so long—a typical bill cycle from start to finish takes about four years, legislative experts say—Cox effectively put his life on hold.

Happy Easter every bodyAn owl made of bald cypress

Posted by Cox carving on Sunday, April 5, 2015

Whereas he typically used to do art shows on the weekends, he now sets up on the side of Route 1 and carves bears and eagles for passersby to purchase. “Some weekends, I do really well and eat well. Other weekends, it’s really slow and I gotta cut the corners,” Cox says.

He moved further out to Manassas in search of cheaper rent, though that also means spending more than three hours a day driving, plus gas costs and $10 a day feeding the meter. He dashes out every two hours to move his car, but sometimes misses the window if he’s in a meeting; parking tickets alone run him $100 a week, by his estimates. And then there are the boxes of donuts he likes to buy for offices that were particularly receptive to the idea. “Wins the bill some good will,” he figures.

All said and done, well, it’s costing him enough in time and money that he doesn’t want to do the math.

“I think I would just be depressed if I added it all up,” Cox says. “But where I’m not making any money here, I tell myself I’m making history and that makes me feel a little better about it.”

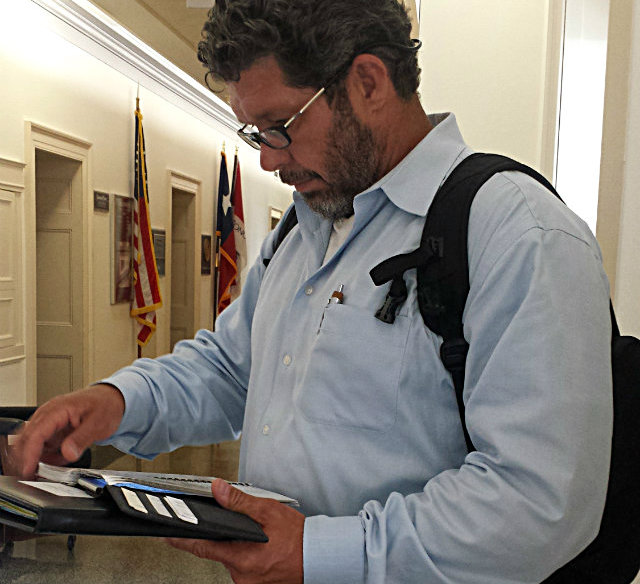

Photo by Rachel Sadon.

Photo by Rachel Sadon.

A genial and earnest guy, people now recognize Cox around the halls of the House of Representatives, particularly in offices from his home state. When we walk into the cluttered office belonging to Rep. Joe Wilson, the staffers greet him by name. In Issa’s office, aides ask if he needs more folders or if he’s there to see the defense legislative fellow he’s been working with. Cox, in turn, asked them all if he would see them later at the annual Congressional baseball game.

Intuitively, he’s been doing what legislative experts call “socializing” a bill.

“You’re literally educating everybody, every staff person who has that portfolio. What it is you’re doing, why you’re doing it,” explains Susan Lukas, the legislative director for the Reserve Officers Association.

One could say he’s learned the art of inside baseball on the Hill.

Cox and an aide to Rep. Joe Wilson in the congressman’s office. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

Cox and an aide to Rep. Joe Wilson in the congressman’s office. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

Although it’s not unusual for an individual to champion a cause on the Hill, it usually has to do with something deeply personal—they are bills that very often have someone’s name attached to them. Cox, on the other hand, has never served in the military, though some of his family members have. And rarely do even the most dedicated citizens take it upon themselves to become a full-time, unpaid lobbyist.

Cox explains that he feels he has a duty. “So much notoriety came along with the Lawnmower Man stories, I felt that I was responsible for doing something better with it. To make a change,” he says. Just like picking up one cigarette butt spiraled into the memorial militia, so has this project become his life.

“He has taken up the mantle of the legislation and become a passionate advocate on its behalf, nobly using his own time, much like he did in 2013, to advance a cause that clearly means a great deal to him,” said Issa spokesman Ben Carnes. “Congressman Issa is encouraged to see citizens like Chris get so involved in the political process and his decision to devote so much of his time and resources to voluntary public service is definitely a notable effort.”

But will the daily slog come to anything?

“You have to educate people about [a bill]. His instincts are right to go around,” said Lukas, who has advised Cox. And in the four months since the bill was introduced, he’s helped get eight new co-sponsors on board.

But she adds that he’d be better off working with groups who can marshal supporters instead of shouldering the entire burden himself. And he’ll have more support next year, when the high-voting military and veteran populations are liable to take notice. “Any bills that can be introduced around an election year is a good way for a candidate to signify how they feel about those things,” Lukas said.

Cox isn’t deterred. While Congress takes its August recess, he’ll spend the month wielding a chainsaw, turning logs into dolphins and sea turtles and bears. Then he’ll head back to the halls of Congress, well-rested and ready to go back to his other job.

Rachel Sadon

Rachel Sadon