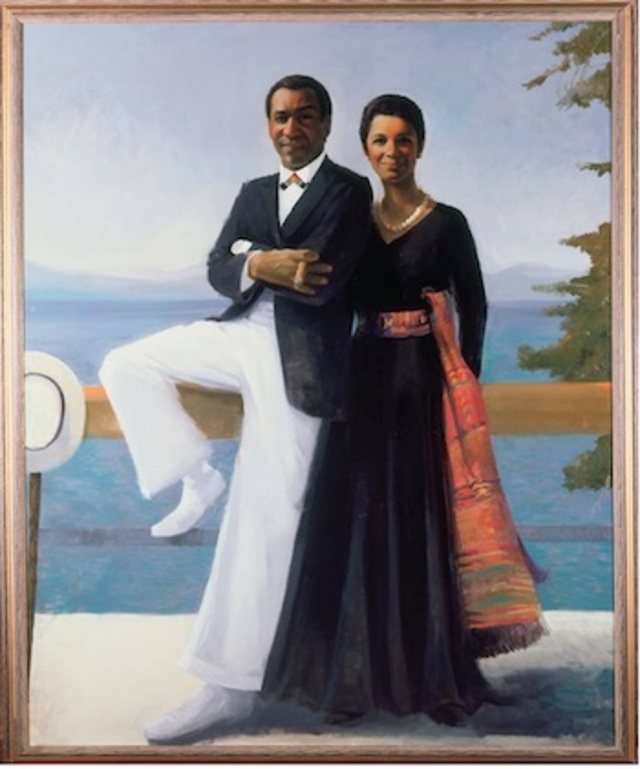

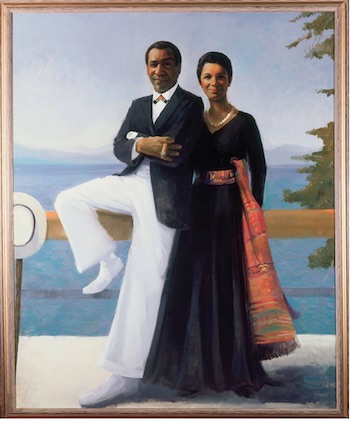

Simmie Knox’s portrait of Cosby and Camille Cosby in 1984 (William H. and Camille O. Cosby Collection/Smithsonian)

Simmie Knox’s portrait of Cosby and Camille Cosby in 1984 (William H. and Camille O. Cosby Collection/Smithsonian)The new secretary of the Smithsonian has defended the decision to not shut down an exhibition featuring the private art collection of Bill Cosby, despite the many, many allegations of drugging and sexual assault.

David Skorton, giving his first interview as secretary of the Smithsonian, told the Washington Post, “As an overriding principle, we have to avoid censorship. I am very much against taking down an exhibition once it has opened.”

The timing of the exhibition ended up being exceptionally poor. The exhibition opened at the National Museum of African Art in November 2014, just as the decades-old allegations against Cosby were picking up steam. It is scheduled to stay open through January. In a video interview with Bill and his wife Camille about the exhibit, the Associated Press delicately tried to broach the subject. Cosby refused to address the issue and demanded that his “no comment” be erased from the interview. The AP released the uncomfortable video as the controversy over the sexual assault allegations snowballed.

Skorton says that the decision to keep the exhibition open was one National Museum of African Art Director Johnnetta Cole took seriously. When he arrived in July, Skorton says the discussions were ongoing: “It wasn’t ignored; it wasn’t ‘Who cares what the public thinks,’ not at all.”

Cole faced criticism for not directly addressing the controversy until she wrote a first-person piece for The Root in August. Cole admitted to having a close professional and personal relationship with the Cosbys, but she defended the exhibition on its artistic merits, not because she defended Cosby’s behavior. She wrote that “this exhibition is not about the life and career of Bill Cosby. It is about the interplay of artistic creativity in remarkable works of African and African-American art and what visitors can learn from the stories this art tells.”

She pointed out that two thirds of the exhibition “Conversations: African and African American Artworks in Dialogue” featured work from the museum’s permanent collection—the remaining third was from the Cosby’s private collection. She wrote:

It is my responsibility as the museum’s director to defend the rights of the artists in “Conversations” to have their works seen. It is also my responsibility to defend the rights of the public to see these works of art, which have the power to inspire through the compelling stories they tell of the struggles and the triumphs of African-American people.

“The Thankful Poor,” 1984 by Henry Ossawa Tanner (Photo by by Frank Stewart/Smithsonian)

“The Thankful Poor,” 1984 by Henry Ossawa Tanner (Photo by by Frank Stewart/Smithsonian)