(Photo by Rachel Sadon)

(Photo by Rachel Sadon)

Police officers responding to 911 calls last month arrived at an apartment complex in Southeast to find a winded security guard with his knee on the back of an unconscious man in handcuffs.

The body worn camera footage released today shows the next nine minutes of the encounter, in which police officers go to get additional restraints, call an ambulance, and administer CPR to Alonzo Smith, who was later pronounced dead at a local hospital. The medical examiner’s office has ruled the case a homicide.

More than a year after launching a pilot for police body worn cameras—and on the same day that the D.C. Council passed a bill allowing District residents to view most footage recorded by MPD officers in public places—it marks the first time that the city has released footage from the program.

Under the D.C. law, the video in Smith’s case would have been exempt from FOIA because the U.S. attorney’s office is investigating, but the mayor has the power to release footage that is deemed of significant public interest.

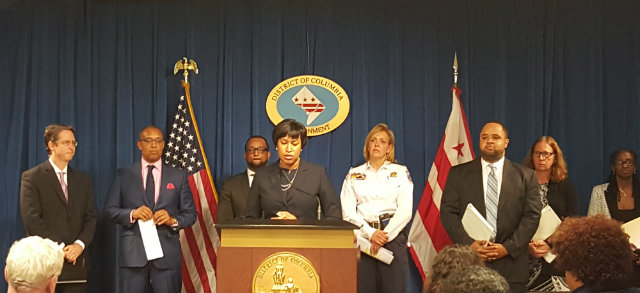

“We’re going to look very closely at any police shooting, in-custody death, or incident where there was serious injury involved. The public wants to know if someone was in legal custody why they died,” Mayor Muriel Bowser said about the decision to release the footage. “To the extent that the body worn camera shows even a snapshot of after-the fact-moments, I think it was important.”

Both the mayor and Police Chief Cathy Lanier urged the public to call in with any information about the investigation, which remains ongoing.

The video shows the Metropolitan Police Department’s response after they were called to the scene of a disturbance at a residential building at 2312 Good Hope Road SE. Two members of the Seventh District, who were each wearing body worn cameras, head up a stairwell and find Smith handcuffed and unconscious when they arrived just after 4 a.m. on November 1.

The security guard, who has knee on Smith’s back, tells the officers that he believes the man is on PCP. Per MPD protocol in such a case, one of the officers goes to get additional restraints and calls an ambulance. Smith was initially lying face down on the the floor with his hands cuffed behind his back; he was unmoving and shoeless.

After the officers turn Smith over and realize that he isn’t breathing, they begin to administer CPR and remove the handcuffs. At one point, they ask if the guards, who are licensed as “special police,” knew Smith; one responds ‘no.’ The officer performing chest compression shouts “Come on man … Come on, wake up!”

All faces in the video are obscured with black circles and a cell phone screen is concealed. It took about five days to redact the video, which was relatively uncomplicated given it was in a closed area without a lot of witnesses, Bowser said. A second video is in the process of being redacted and will be released “in the coming days.”

Going forward, General Counsel Betsy Cavendish will review all footage from law enforcement-involved shootings, deaths in custody, and incidents of serious bodily injury involving officers. “We will weight the benefits of disclosure against the possible harm, such as health and privacy concerns, protecting confidential police sources and witnesses,” Bowser said.

The video in this case has already been made available to Smith’s family, who have demanded to know why the 27-year-old teacher was in custody and what happened to him. Activists held a rally on Saturday calling for “Justice for Zo.” Speaking to the crowd, Smith’s mother, Beverly Smith, vowed to continue pressing for answers. “As long as I have breath in my body, you will not cover my son’s death,” she said.

The medical examiner’s office ruled the death a heart attack that was complicated by “acute cocaine toxicity while restrained” with “compression of torso” as a contributing factor.

The security guards, who were employed by Blackout Investigations, are licensed as “special police,” which requires 40 hours of training in the District and affords arrest powers.

Smith’s death was the second this year while in custody of special police officers. Bowser said that MPD initiated an investigation into the procedures for licensing such officers following the first incident, which occurred at a hospital in October. The results of the probe are expected in January.

Also speaking at the press conference, Councilmember LaRuby May expressed her condolences to the Smith family and her anger that the “loss of life of African Americans in Ward 8 has become common.” She also argued that the training of special police has been overlooked because of a preponderance of them in black communities.

“If there were more armed officers in white buildings, we would have a different perspective on the accountability and the training of special police,” May said.

Both Bowser and Lanier responded that the special police are necessary for the security of the entire city—there are more than 17,000 such officers employed by 122 companies around D.C. “They weren’t out for a walk. They responded because residents said they needed help,” Bowser said. Lanier added that MPD did 77 checks in Ward 8 alone this year to ensure the officers are following protocol. “They are saving lives and preventing crimes and doing really good security work; they are very, very necessary,” Lanier said.

But one thing they could all agree on was that the body worn cameras only provided a snapshot of what happened, since the footage only begins after the MPD officers arrives.

It was clear, Lanier said, that they arrived at the end of a “pretty significant struggle.” Nonetheless, neither MPD or special police officers are trained to restrain people with their knees.

“We don’t have the answers to what exactly happened. We have bits and pieces of facts,” Lanier said. “It shows that the cameras are not always going to give the answers.”

Warning: This video contains graphic footage.

Rachel Sadon

Rachel Sadon