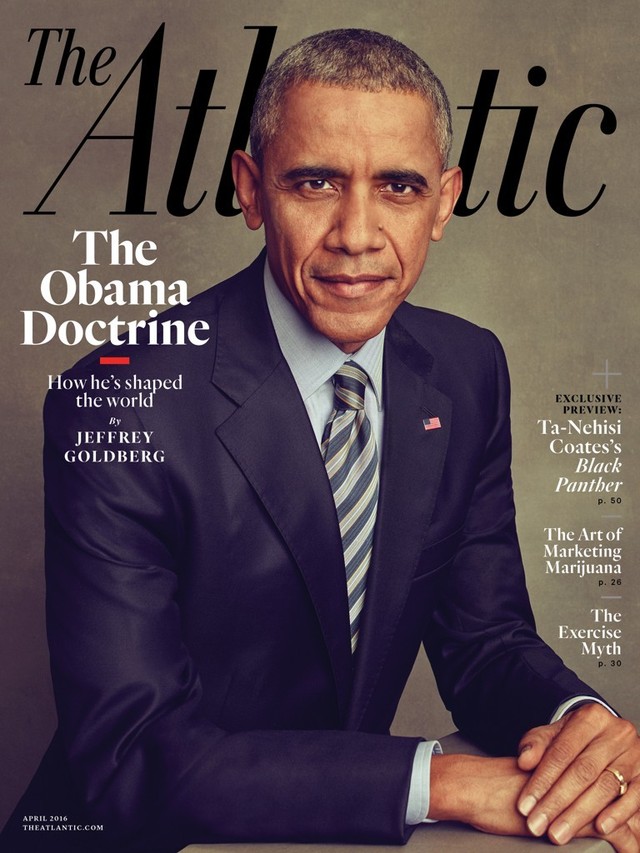

In the April issue of The Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg lays out “The Obama Doctrine” in an illuminating long-form cover story based on hours of interviews over several months with the president. On Wednesday, Goldberg, the magazine’s national correspondent, will share his insights with his editor-in-chief, James Bennet, at Sixth & I Historic Synagogue at 7 p.m.

In the April issue of The Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg lays out “The Obama Doctrine” in an illuminating long-form cover story based on hours of interviews over several months with the president. On Wednesday, Goldberg, the magazine’s national correspondent, will share his insights with his editor-in-chief, James Bennet, at Sixth & I Historic Synagogue at 7 p.m.

Goldberg’s article begins with a day seen very differently by Obama critics and supporters. The “red line” on U.S. intervention in Syria, the president had said in 2012, would be Bashar al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons on civilians. Horrifyingly, the following August, Assad’s army murdered more than 1,400 Syrians with sarin gas.

At the advice of Secretary of State John Kerry, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Senate hawks John McCain and Lindsay Graham, and others, air strikes had been ordered to follow through on the threat. But most of Congress did not give their blessing, and after further consideration of the consequences, Obama called them off. Doing so angered many people inside the administration and out. It was a “gamble” with nonintervention, at least in this case.

With a five-year perspective on the war in Syria, and current and upcoming challenges with other regions, Goldberg probes the president’s worldview.

Obama may have a gift for flourishes of rhetoric, but his approach as commander-in-chief has veered practical. In the interview, he calls out critics who tout rose-colored versions of Ronald Reagan’s and George W. Bush’s foreign policies. He comments on “free riding” foreign leaders who leave it to the U.S. to intervene. And as he and Goldberg discuss Syria, Russia, ISIS, Ebola, and climate change, it is clear that the president knows he does not always react the way some think he should.

But that has been intentional. “I think that the best argument you can make on the side of those who are critics of my foreign policy is that the president doesn’t exploit ambiguity enough. He doesn’t maybe react in ways that might cause people to think, ‘Wow, this guy might be a little crazy,'” Obama told Goldberg.

The president then broke down that tactic, used by Richard Nixon: “So we dropped more ordnance on Cambodia and Laos than on Europe in World War II, and yet, ultimately, Nixon withdrew, Kissinger went to Paris, and all we left behind was chaos, slaughter, and authoritarian governments that finally, over time, have emerged from that hell. When I go to visit those countries, I’m going to be trying to figure out how we can, today, help them remove bombs that are still blowing off the legs of little kids. In what way did that strategy promote our interests?”

This is one of the main points of the Obama doctrine: Despite contradictions, which are named in the article, the president has taken a largely realist worldview that military intervention should be avoided unless the U.S. is under direct threat. What “direct threat” means is controversial, and questions persist surrounding the administration’s use of drones (CIA director John Brennan is quoted as saying he agrees that “sometimes you have to take a life to save even more lives”). But Obama is informed by lessons spanning decades of American foreign policy that have made him highly cautious about putting boots on the ground.

“You know, the notion that diplomacy and technocrats and bureaucrats somehow are helping to keep America safe and secure, most people think, ‘Eh, that’s nonsense,'” the president said. “But it’s true. And by the way, it’s the element of American power that the rest of the world appreciates unambiguously. When we deploy troops, there’s always a sense on the part of other countries that, even where necessary, sovereignty is being violated.”

The whole article is worth reading for an unprecedented look into how and why Obama’s foreign policy came to be, and where it is likely to take us in the waning months of his presidency.

Tickets to the talk can be purchased online for $15, which also includes a 1-year subscription to The Atlantic. Seating is general admission and doors open at 6 p.m.