“Off the Train.” (Meredith Hanafi)

“Off the Train.” (Meredith Hanafi)

Immigration has been one of the hottest topics of this election cycle. But this weekend, conversation in one corner of our nation’s capital will be focused on a century old migration story—one that many Americans can call their own.

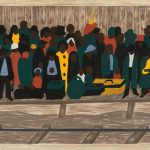

Co-presented with Washington Performing Arts, in cooperation with The Phillips Collection, Step Afrika!’s The Migration: Reflections on Jacob Lawrence is a direct response to the African-American painter’s famous Migration Series. In earthy tones of brown, black, deep green, and muted red, Lawrence painted the 60-piece series in the early 1940s. But the journey they depict began decades before and ended long after that.

Together, the small panels depict the Great Migration, the mass relocation of African-Americans from the rural South to cities in the Northeast, Midwest, and West. Between 1915 and 1970, about six million African-Americans picked up their lives and families, and moved. As in many migration stories, the choice to leave wasn’t made lightly.

“There’s no African American not touched by the Great Migration,” Step Afrika! founder and executive director C. Brian Williams says. A Southern man, Williams says his family’s business kept them in Texas, even though his grandmother wanted to leave. Others in the company can speak of relatives who took trains north or booked a bus to D.C.

“We do feel like we’re paying tribute to our own families and to the brave men and women who made the journey, who left the South against a lot of odds,” Williams says.

He hopes audiences will connect with that story, but also leave thinking about their own. How did they get here? Why would their family—whether their parents or great-great-grandparents—leave their homes and countries? What conditions would force a family to separate, to start over far from everything they’ve ever known?

“What I hope is that the work creates more conversation in terms of people of all cultures and backgrounds sharing their unique, crazy migration story because we all have them: people who changed their names, people who left other areas, African-Americans who were forced to come here,” Williams says. “When we share that we start to recognize that this journey to opportunity is really in each and every one of us.”

Williams says the concept behind The Migration came to him about as quickly as Dorothy Kosinski, director of The Phillips Collection, accepted it. Williams says he was familiar with Jacob Lawrence’s iconic series, but was unaware that roughly half of the panels live right here in D.C.

While judging a synchronized swimming contest in 2010, Kosinski told Williams about the modern art museum’s collection of Migration paintings. “When she told me that, I was like, I would love the opportunity to interpret this work on stage,” he remembers. To his shock, Kosinski immediately said yes.

In many ways, the pairing is a match made in curatorial heaven. Phillips Curator Elsa Smithgall says the museum has a long history of collaborating with the community across disciplines. “We see that the visual arts is important in the broader context of not just dance, but theater, poetry, music, and so our programming has embraced that multiplicity,” she says. “I think that art speaks across all these genres so powerfully and it enriches the dialogue to be able to connect our audiences in this way.”

As a company, Step Afrika! makes a point of connecting with audiences. Performers frequently break the fourth wall, which is fitting considering their art form’s roots as a means of communication. Step is a rhythmic style of dance that incorporates clapping, stomping, and other percussive uses of the human body. It pulls from the South African Gumboot dance, which working class Black miners developed in order to communicate with and entertain each other.

Step as we know it was developed and popularized by Black Greek Letter Organizations and remains a major part of that culture, both on campus and beyond. Step Afrika! has taken it to a professional level of artistry.

“I think that there’s an interesting idea in that fight to be able to express oneself,” Smithgall says. “There’s an agency in the fact that they’re trying to overcome hardship through the movement, through this innovative use of their bodies as an instrument and a form of communication that I see as a parallel to the kind of characteristics that embody the spirit of the Black migrants of the Great Migration.”

Williams calls step an American art form created by African-American people to tell their own story. “I think stepping is so appropriate for this particular series because it, just like the Great Migration, is a uniquely American experience, rooted here,” he says.

C. Brian Williams says he hopes audience members leave thinking about their own migration stories, and those that continue to unfold today. Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 60: And the migrants kept coming.,1940-41. © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / ARS New York

C. Brian Williams says he hopes audience members leave thinking about their own migration stories, and those that continue to unfold today. Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, Panel no. 60: And the migrants kept coming.,1940-41. © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / ARS New York

September 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of Jacob Lawrence’s birth, and next month, The Phillips Collection and New York’s Museum of Modern Art will reunite all 60 panels of The Migration Series in People on the Move: Beauty and Struggle in Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series. The exhibit will be on view at The Phillips Collection through January 8, 2017.

When that opens, The Migration will be “on the move” too. First performed in 2011, this time the show is bigger, better, and it’s going on tour. After D.C., it will travel to Atlanta, Iowa City, St. Paul, and Philadelphia.

The production goes back in time then rolls forward through history. From the Middle Passage to the Southern states to Chicago, the show will provide a visual history lesson in music and dance. This time around, more effort went into the costumes, making sure they’re period appropriate. “You’ll watch the hemlines go up,” Williams says.

As the styles change, so will the mood. Performers will share the anxiety, excitement, fear, joy, and pain of the Great Migration and the time leading up to it. Audience members will follow the physical and emotional journey depicted in Lawrence’s famous panels.

“If you’ve ever seen Jacob Lawrence’s work in the museum, you’ll see the paintings as you’ve never seen them before,” Williams says. “The paintings on the wall are amazing to see—and I really recommend everybody go see them at The Phillips Collection—but they’re very small.”

During the step performance, audience members will see more than a dozen of the paintings enlarged, projected on to the set.

In Lawrence’s artwork, most of the migrants are free of distinguishing features. While some have faintly defined eyes, noses, and mouths, most are just clothed, brown figures, their emotions portrayed more by body language than facial expressions.

“What we’re trying to do is we’re trying to let you see the characters behind that painting a little bit,” Williams says. Who might the people that Jacob Lawrence painted be?”

Smithgall says seeing this performance could affect audience members in a way that viewing the paintings or learning about the Great Migration in school might not.

“I think that you can read something in a book, but that really doesn’t resonate in the same way as seeing it performed before you,” she says. “There is something incredibly powerful and engaging about being caught up in this moment of the performance, the movements, the projected images, the costumes. There’s just a way that that experience engages and actually really stimulates you in your senses in ways that could be very different from just standing before a work of art.”

There will be three performances of The Migration at the University of the District of Columbia Theater of the Arts this Friday, September 30 through Sunday, October 2, 2016. Tickets are $30-$45.