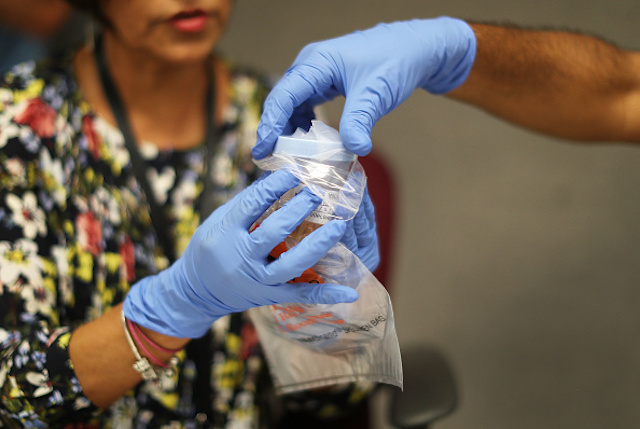

Florida Department of Health workers package up a urine sample to be tested for the Zika virus in September 2016. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

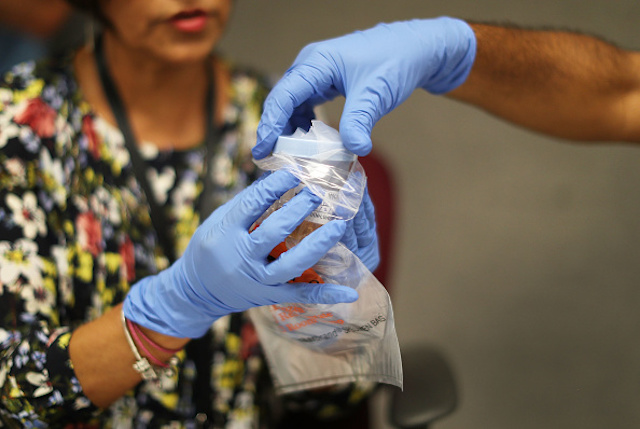

Florida Department of Health workers package up a urine sample to be tested for the Zika virus in September 2016. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

This post has been updated.

Officials from the D.C. Department of Forensic Sciences Public Health Laboratory announced Thursday that a Zika testing error resulted in officials telling two pregnant women that they did not have the mosquito-born virus, when they were actually positive for an unspecified flavivirus that could be either Zika or Dengue. But officials are treating the cases as being positive for Zika.

The forensic agency is responsible for Zika testing for patients seen by D.C. health care providers. It is currently retesting nearly 350 other specimen samples, many of them from pregnant women, to see if they were also improperly diagnosed as being negative for Zika.

At a press conference this afternoon, Dr. Anthony Tran, the new public health director at the laboratory, did not say if any of the pregnant women have since given birth, or if their babies have contracted microcephaly—a condition affiliated with the virus.

Tran described the Zika testing mistake to reporters as a “technical formulation and calculation error.” He said he discovered the error with the lab’s Zika MAC-ELISA test on December 14, and immediately stopped administering it.

After a review, lab officials sent 409 specimens collected between July 14 and December 14, 2016 to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention and CDC-approved sites for retesting. This includes samples from 294 women who were pregnant when they took the test.

It discovered the false negatives on Wednesday. The department has received 62 results thus far—two from the positive pregnant women, and 60 from others who were still found to be negative. That leaves 347 people waiting for the new results, which Tran says he should have in coming weeks.

Tran said that the agency has given all of the results to health care providers, which are responsible for relaying the information to their clients, and will continue to do so as the new ones arrive.

In May 2015, the Pan American Health Organization issued an alert about the first confirmed Zika virus infections in Brazil. Since then, outbreaks have occurred in more than two dozen countries. The World Health Organization declared a “public health emergency of international concern” in February 2016, followed by the death of a man in Puerto Rico—the first fatality in the United States caused by the mosquito-borne virus—in April 2016.

The most common way to contract the virus is from the bite of an infected mosquito, but there have been some reports of Zika being spread through blood transfusion and sexual contact (all of these reports are under investigation).

Only 20 percent of people who have the virus get symptoms, the most common of which are fever, rash, joint pain, or red eyes. According to a recent CDC study, some babies aren’t diagnosed with microcephaly until several months after birth. Researchers are recommending continued medical care and follow-ups for infants who are exposed to Zika prenatally.