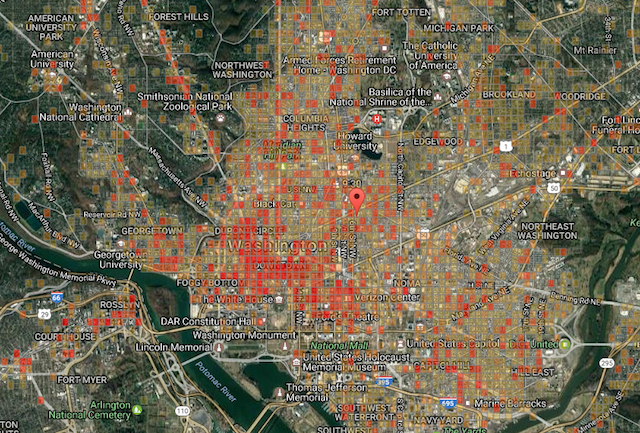

The more intense the color on this map, which apes the lingo used by predictive policing formulas, the more dense the white collar crimes. (Image courtesy of The New Inquiry)

The more intense the color on this map, which apes the lingo used by predictive policing formulas, the more dense the white collar crimes. (Image courtesy of The New Inquiry)

Algorithms and other forms of “big data” have a veneer of objectivity—the numbers don’t lie!—that obstruct a larger truth: yep, formulas and machines have their own biases.

Programs like “predictive policing,” which use software to determine how likely a person is to re-offend or where crimes will happen, are based on formulas that are biased against black people, ProPublica found.

And you don’t have to watch Minority Report to see predictive policing in action in D.C.—the Washington Regional Threat and Analysis Center has a predictive policing platform.

Now, The New Inquiry, a left-leaning political and cultural journal, is proving the point differently—through epic and thorough trolling. In a new project called White Collar Crime Risk Zones, which promises to “predict financial crime at the city-block-level with an accuracy of 90.12 percent” using data from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority and “industry-standard predictive policing methodologies, including Risk Terrain Modeling and geospatial feature predictors.”

“Unlike typical predictive policing apps which criminalize poverty, White Collar Crime Risk Zones criminalizes wealth,” authors Sam Lavigne, Francis Tseng, and Brian Clifton write.

You can learn more about the methodology in a white paper that shows total commitment to the gambit. Here’s one hilarious snippet:

Image courtesy of The New Inquiry.

Image courtesy of The New Inquiry.

While D.C. does not have the skyscrapers that create a “unique behavior setting” for white collar crime, (who’d have thought the Height Act was a crime-prevention measure?!), tabulations from the project show that large pockets of the city are indeed White Collar Crime Risk Zones, especially in downtown D.C.

So be careful out there, Washingtonians.

And if you’re interested in using street policing techniques to target white collar crime, check out Jessica Williams’ Daily Show report from 2013 on a different application for stop-and-frisk.

Rachel Kurzius

Rachel Kurzius