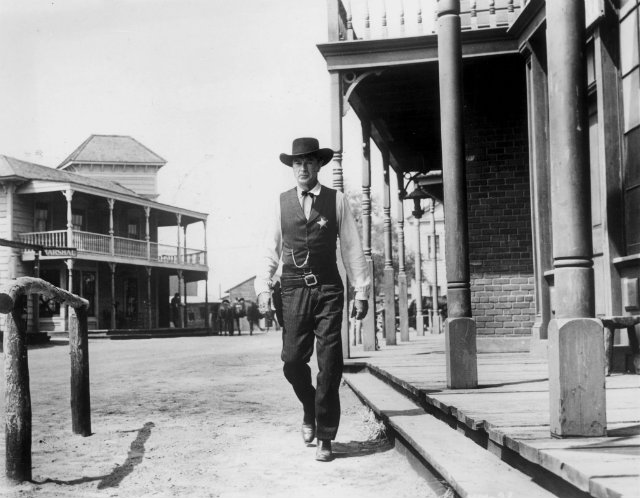

Gary Cooper stars as Marshal Will Kane in the 1952 classic High Noon (Courtesy of the Avalon).

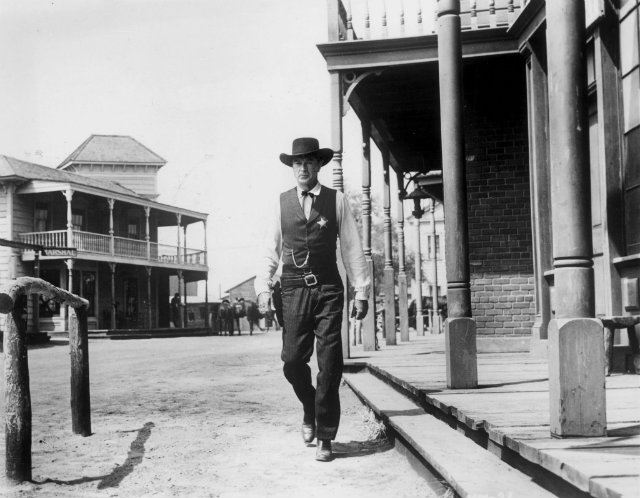

Gary Cooper stars as Marshal Will Kane in the 1952 classic High Noon (Courtesy of the Avalon).

To the casual viewer, High Noon is a riveting Western with a classic performance from Hollywood icon Gary Cooper. But, author and Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist Glenn Frankel argues, a closer look reveals deeper connections: to the Red Scare, to threats against free expression and to the hidden wonders of film history.

“You can’t underestimate how much power and influence Hollywood has over our national culture and our dreams and our vision of ourselves,” Frankel says.

That’s the underlying thesis of Frankel’s latest book High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic, which follows his 2013 deep dive into John Ford’s The Searchers. Frankel will discuss his new book after a screening of High Noon during the Avalon Theatre’s annual spring benefit on Sunday.

High Noon — ranked 33rd on the American Film Institute’s list of the greatest films of all time — stars Cooper as Will Kane, longtime marshal in a small New Mexico town. He’s on the verge of retiring and moving elsewhere with his new wife Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly) when he gets word that outlaw Frank Miller and his henchmen are on the way to Kane’s town, hoping to exact revenge; Kane threw Miller in jail years ago. Amy tells her husband he should just run away, but Will is resolute, rounding up the townspeople and stirring up concerns. A standoff ensues.

The film’s themes of loyalty and courage in the face of internal and external threats couldn’t help but take on greater political resonance at the time. As Frankel details in his book, the film’s screenwriter Carl Foreman — a former member of the Communist party — was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee while he was writing High Noon. He refused to identify any current or former members, and as a result earned “uncooperative witness” distinction, which made him vulnerable to the Hollywood blacklist. Entertainment industry professionals like Foreman suspected of Communist involvement were one of the most scrutinized targets of the House committee’s investigations.

Foreman eventually sold the screenplay rights to his producing partner Stanley Kramer and fled to Britain. They later had a dispute over creative authorship of the film. In the meantime, the film’s story, in which a man defies temptations to avoid standing up for his beliefs, strikes many as an allegory for the anxieties of the late 1940s and early 1950s, particularly for Hollywood types terrified of ending up on the blacklist.

These ideas captured Frankel’s imagination a few years ago after a presentation from a colleague at the University of Texas – Austin — and they’ve now taken on a renewed significance amid a political climate marked in many ways by fear of the unknown. Frankel started work on the book before some of those headlines, but he now sees the explicit parallels he was drawn to all along.

“The blacklist is a complex subject to get into,” Frankel says. “The movie gives characters and vehicles to take me through that story.”

Cooper, Foreman, Kramer and Zinneman have all passed away, but Frankel managed to reach Zinneman’s son, Cooper’s daughter and two of Kramer’s close relatives, as well as film scholars, political historians and a litany of primary source documents. The book goes into detail about shots and lines of dialogue that were molded and reshaped by current events, and explores Hollywood figures tangential to High Noon who also had a brush with the blacklist.

It also highlights a fact that surprised Frankel — the film’s director, screenwriter and producer were all either Jewish immigrants of sons of immigrants from eastern Europe, and Cooper’s parents were British immigrants as well.

“Hollywood, as it does now but even more so in those days, just attracted talent from all over the world,” Frankel says. “It was a time of great disruption in the world, before and after World War II.”

The Avalon’s executive director Bill Oberdorfer saw Frankel’s book as an ideal partner for the theater’s seventh annual fundraising effort, the proceeds of which go towards the Avalon’s student programs. Oberdorfer tells DCist he’s hoping to raise $100,000 from the High Noon event.

In the meantime, Frankel is on the hunt for his next book topic. The challenge is to find a movie with fascinating real-world relevance that hasn’t already been exhaustively analyzed; he’s already ruled out Citizen Kane for that reason.

“A great movie shines a light of the times that it’s made in,” Frankel says. “…I think I’m going to stay in this subgenre a bit longer.”

Frankel will discuss his book on Sunday after a 7 p.m. screening of the film at the Avalon Theatre. Tickets are $50 for the screening and discussion. Buy tickets here.