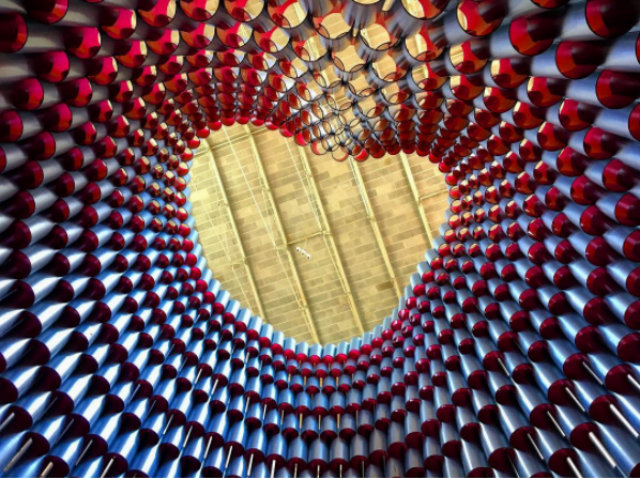

The magenta-ringed heart was never supposed to appear.

The National Building Museum’s The Hive summer exhibit was pitched as a series of domed chambers, designed to create different acoustic properties in the cavernous Great Hall. While domes traditionally don’t sag in at the apex, the biggest of the three structures has a noticeable droop inward—one that has worsened significantly since the opening on July 4.

“Once you build the circles, it sets. But what we didn’t anticipate was some of these pieces flattening off a little bit,” says Cathy Frankel, the National Building Museum’s vice president for exhibitions and collections. “We thought we could get it back into shape. It was too high and too heavy, and in the end we couldn’t.”

The installation was actually never even fully finished, as Washingtonian has reported. Builders starting noticing a problem when they got to the seventh layer of tubes, as their weight started causing the structure to lean in on itself. When The Hive opened to the public, the smaller structures were completed, but the biggest one was about ten feet shorter than originally envisioned.

Since then, the oculus has noticeably warped, and it appears rather ominous to the untrained eye.

Building Museum officials and engineers have been keeping a close eye on it, measuring the daily changes with a laser and speaking daily with the Studio Gang architects who designed the installation. But they aren’t worried about a potential collapse.

“‘The engineers are describing it as finding its equilibrium,” Frankel says, adding that while she was panicked by the whole turn of events, the builders and architects assured the non-expert museum officials that it wasn’t entirely unexpected.

When they did modeling back in the spring, engineers pinpointed the areas that were likeliest to have issues. If each structure had been designed and built separately, there might not have been a problem. But in addition to the main entrance, the chambers are interconnected by two interior entryways, which means that the base layers are broken up in three places.

“The models that were done for this showed the two spaces over the doorways were points of deflection where there was a possibility of this thing not staying in the round. The places it’s happening are exactly there,” Frankel says. The movement up top is “something we are watching, but nothing we are concerned about.”

At this point, it seems to have stopped shifting.

“We’re using a common building material in an epic new way,” National Building Museum director Chase Rynd told reporters at a press preview before opening. The fact that it was still unfinished “shows how complex and challenge this engineering feat has been to accomplish in a very, very short amount of time,” he said.

The tubes are traditionally used to pour concrete, not make structures. Studio Gang came up with the idea of cutting slots to connect them, and conducted crushing tests to make sure they could withstand the weight.

“It has to span over the top of our heads without falling down and be safe and be constructible,” Jeanne Gang said at the time. “This has all the constraints of any real building. It doesn’t have wind, but it does have gravity.”

She noted that traditionally such catenary domes are built using falsework, temporary scaffolding that keeps the structure in place until it is completed and can hold all the pieces in place. But it would have cost tens of thousands of dollars and taken additional weeks to complete—money and time that the Building Museum was unable to pour into a temporary exhibition.

The museum is taking the opportunity to use the missteps as an educational experience. Rather than hiding away the materials that never got used, they’ve left them out on the floor and are building a mini-model to show visitors how the structure was put together, and what went wrong.

“It adds another layer of conversation about whats happening,” Frankel says. “It was an educated experiment with all the right people in the room, but this is innovation. It’s never been done before like this before.”

Previously:

Photos: National Building Museum’s ‘Hive’ Is An Actual Series Of Tubes

National Building Museum Is Giving Us Hives This Summer

Rachel Sadon

Rachel Sadon