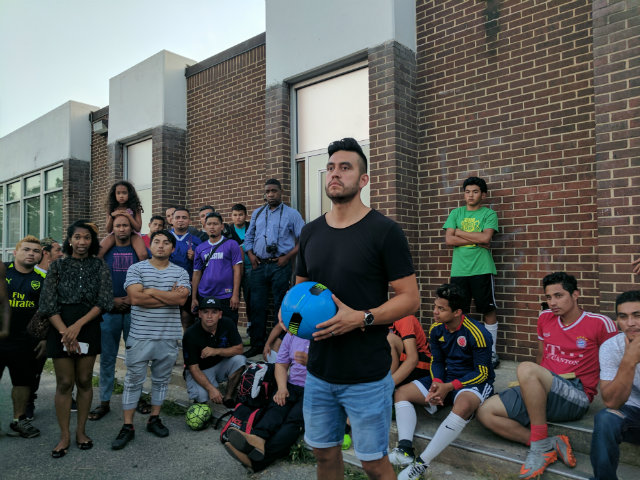

The field behind the Tubman Elementary School in Columbia Heights is usually in constant use on weeknights. But there were no community games on Wednesday as the neighborhood players waited for a league to show up. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

The field behind the Tubman Elementary School in Columbia Heights is usually in constant use on weeknights. But there were no community games on Wednesday as the neighborhood players waited for a league to show up. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

See here for an update to this story.

First came a sports league that uses the field on weekends. Then the bocce ball players started showing up on Tuesdays.

The largely black and Latino community that has played soccer for years at Tubman Elementary School in Columbia Heights accepted it peacefully. Just as they welcome anyone to play in their own pick-up games, the players were willing to accommodate the newcomers that wanted to use the field in other ways.

Then they were pushed off the field entirely.

Several dozen people were gathered, per usual, last Wednesday afternoon when a group of uniformed soccer players showed up and announced they were entitled to the field. ZogSports had received a permit to use the field on Monday, Wednesday, and Thursday nights—leaving no other weeknight available for neighbors that call the space their second home.

“This is our way of life. After work, everyone is here on the field,” says Nico Mondesir in Spanish. “This field is our community.”

When he moved to Columbia Heights about two years ago from the Dominican Republic, he found pick-up games that were open to everyone, regardless of age, race, or ability.

“The only time we don’t come out to play is when there’s a lot of snow,” says Wilbur Rosales, who has lived in the gentrifying neighborhood for 22 years, in Spanish.

“We’ve always come here—back when the field looked like this,” he adds, pointing to gravel at the edge of the field, which had artificial turf installed in 2009.

Since then, the players have been pooling their money to replace the nets—collecting a dollar here, five dollars there, until they reach the $200 that it costs to buy replacements. “They last a year, no more,” Rosales says.

The neighbors have also kept the area clean, and they make room for kids to play on the field’s edge or in the games themselves. Rosales’ 14-year-old daughter often joins in with the group of largely adult men.

“This is the go-to spot for everyone in the neighborhood,” says James Akinsanya, who grew up in Columbia Heights and frequently joins the pick-up games. “It’s right here. It’s easily accessible, and it’s a pretty nice field. We come over here and we take care of it and we play soccer, that’s about it.”

So when the league players showed up, the group was confused. There was a language barrier for some, but they also didn’t really understand the situation itself; nobody had ever had a permit to play soccer on a weeknight. Everyone usually just showed up and joined in.

The community invited the league players to get in their rotation—typically ad hoc teams form and play for ten minutes before rotating to a different team—but the new group declined.

Frustrated and upset, the neighborhood players refused to go. A city official showed up and explained that, indeed, the league players had a permit.

One of the community members decided to take down the nets that they had collectively bought. A police officer showed up and gave him a fine and a five-year ban on using city fields, according to several people who witnessed the interaction.

Omar Gonzalez helps lead a meeting between city government officials and neighborhood residents in a nearby parking lot overlooking the field, where a ZogSports league game was taking place. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

Omar Gonzalez helps lead a meeting between city government officials and neighborhood residents in a nearby parking lot overlooking the field, where a ZogSports league game was taking place. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

The situation is nearly an exact mirror of one that played out in San Francisco a few years ago, although that involved damning video evidence of white men callously kicking children off a field in the largely Hispanic Mission neighborhood. After an outcry, the city government eventually changed the permitting process.

It’s clear that the District government is taking this situation seriously, too. Five city officials showed up to a community meeting Wednesday night to hear feedback and present a temporary solution.

Jackie Stanley, a community outreach coordinator for the Department of General Services, offered to write a permit and waive the fee for neighborhood players to use the field, but at times that the residents said don’t make sense for them (before 6:30 p.m. on Wednesdays and between 6 and 8:30 p.m. on Friday and Saturday nights).

“We wanted to hear what the concerns are so we can make this right. We’re listening and we’re taking notes and we’ll have a follow up,” Stanley told the players gathered on a parking lot, which overlooked the field where the league game was ongoing. “Please be mindful the group does have a permit Monday, Wednesday, and Thursdays.” Stanley declined to say if the agency would be willing to move the private league to another field in DGS’ portfolio.

The permit issued to ZogSports costs $95 an hour, for a total of nearly $4,000 for the summer . A spokeswoman for the company said that they plan to stay.

“We have 120 players scheduled to play at the Harriet Tubman Elementary School field for the 17 days remaining on our current permit,” ZogSports’ general manager Kendra Hansen said via email. “We hope to fulfill our commitment to them this season.”

For participants to join in, it costs $1,200 per team.

Hansen said that they have applied to use this particular field before, but this was the first time it had been granted.

“Many residents of the Columbia Heights community are ZogSports participants and have asked to play on a field in their neighborhood,” she added. “We’ve spent many years trying to find a great space in Columbia Heights. Our participants were very excited when we were granted a permit for the Harriet Tubman Elementary School field for the first time ever this year.”

It is little wonder that primarily white sports leagues have seen increased demand for play in Columbia Heights. In 2012, it was named one of the fastest-gentrifying neighborhoods anywhere in the entire country.

But the neighbors say they don’t want to make this an us-versus-them conflict. “We’re not trying to villainize anybody. Everyone has a right to play on the field,” says Omar Gonzales, a 30-year-old native Washingtonian who helped translate and coordinate the meeting. “We really just want fairness for the field and some time for the community.”

“The league is really not at fault,” added Lauren Greubel, who lives in the neighborhood and frequently hangs out while her husband, Nico Mondesir, plays. “They’re just trying to make money and do their job. Ultimately this just shouldn’t be allowed to happen on a space that’s used daily by the community.”

Players and city officials posed for a photo after the meeting. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

Players and city officials posed for a photo after the meeting. (Photo by Rachel Sadon)

A part of the issue is that the field is managed by the Department of General Services, because it is on the site of a public school, rather than the Department of Parks and Recreation.

While DPR mandates that groups seeking a permit have a letter of support from the local Advisory Neighborhood Commission, that that isn’t the case for DGS. Local representatives only found out about it after the altercation took place on the field last week, which happened to be on the same night as the ANC was meeting inside the school.

A 1982 law governs the DGS permitting process for leasing school land. The obscure regulation, which requires permits for anything more than a three on three game, is “probably only now coming to light because, as the city grows and we have fewer spaces and more people, now we’re having these conflicts,” says ANC commissioner Kent Boese, who has announced a run for the Ward 1 D.C. Council seat in next year’s election. “This is a case where a 35-year-old law is no longer meeting the needs of our community, so it’s time to revisit that … but that’s a long term fix.”

In a letter to DGS’ director, Ward 1 Councilmember Brianne Nadeau wrote that the use of fields should be prioritized in the following order: students and the school community, then neighbors and community groups, followed by leagues and other permitted uses. The situation “requires a larger discussion about how we prioritize our green space and make it available to our community.”

When DGS offered to write up a permit for the available hours, as required under the regulation, the community explained that they didn’t want one; they wanted it to be time for open play.

One meeting participant, a white resident, told a story of what happened when his nephew came to visit. They took him to the Mall and the National Zoo, but the experience that the five-year-old treasured the most was when he wandered onto the Tubman field. Two men who were playing and conversing in Spanish let the child join in and kick the ball around. The neighbor put it this way: “You can’t schedule time for community to happen.”

The bigger issue, though, is that the proposed times conflict with residents’ work schedules and a movie night that takes place on Friday nights.

“The recommendation was commendable but it doesn’t fix the problem and it’s inconsiderate of the people who are actually using this space,” said Sheika Nikole Reid, a community activist and architecture professional who grew up in the neighborhood. “It really speaks to the privatization of people who can afford a permit to dominate space, and it’s really offensive to people who can’t.”

The city officials, which included two representatives from the Mayor’s Office of Community Relations and Services, pledged to work on a long-term solution.

“We take this very seriously and we’re going to work toward a solution so you can return and play,” Eduardo Perdomo, with the Mayor’s Office on Latino Affairs, told the group.

In the meantime, the players are gathering signatures on a petition (they’re now at over 900)—and waiting.

“Everyone who is here are neighbors. I know the majority of them,” says Rosales. “This is the only diversion we have.”

Before the league players arrived last night and the community meeting started, Gonzalez surveyed the field, where groups of men were standing around and informally kicking balls around.

“Usually right now people would be playing [a game],” he said. “But since they know people will be playing here, they’re just standing around, afraid they’re going to get kicked off.”

The colorful mural that wraps around the field makes observations about the community: “It’s diverse.” “It’s musical.” “It’s lively.” “It’s changing.”

Added Mondesir: “I feel displaced … You have to understand, this is destroying a way of life, and a community.”

Rachel Sadon

Rachel Sadon