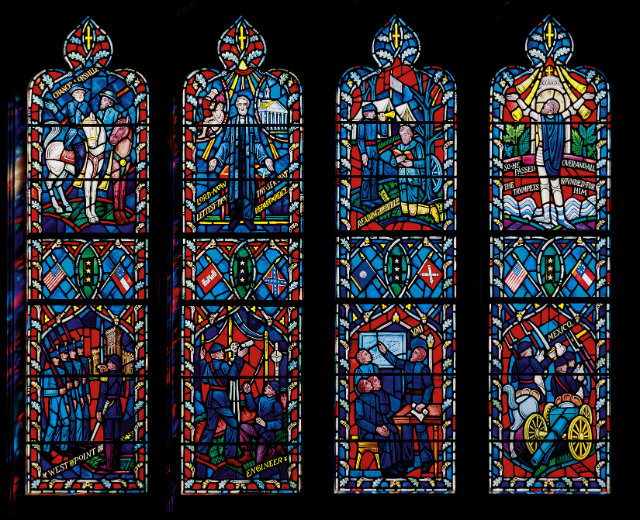

The Lee-Jackson window bay at the National Cathedral (Photo courtesy of the National Cathedral)

The Lee-Jackson window bay at the National Cathedral (Photo courtesy of the National Cathedral)

The National Cathedral is removing a set of stained glass windows that honor Confederate generals.

The Cathedral Chapter voted on Tuesday evening to immediately remove the window bay, installed in 1953, that depicts Stonewall Jackson as a crusader receiving trumpet blasts from the heavens and describes Robert E. Lee as a “Christian soldier beyond reproach.” Scaffolding has already been erected to begin the process.

“The Chapter believes that these windows are not only inconsistent with our current mission to serve as a house of prayer for all people, but also a barrier to our important work on racial justice and racial reconciliation,” the National Cathedral announced in a statement. “Their association with racial oppression, human subjugation, and white supremacy does not belong in the sacred fabric of this Cathedral.”

The Cathedral Chapter is made up of more than two dozen trustees, including clergy, business and education leaders, and architectural and building experts. The vote passed with a “wide majority,” says National Cathedral spokesperson Kevin Eckstrom, who added that the chapter does not release vote tallies.

The decision comes more than two years after now-retired Reverend Gary Hall issued a statement calling on the institution to remove the windows and “commission new windows that would not whitewash our history but represent it in all its moral complexity.” Hall was prompted by the deadly shooting of nine worshippers at a historic black church in Charleston in June 2015, and pictures that emerged of shooter Dylann Roof with the Confederate battle flag.

In August 2016, the cathedral removed the window panels featuring the Confederate battle flag with little fanfare, replacing them with red and blue panes. But a task force assembled to examine the windows called for them to remain, at least temporarily, to prompt a broader discussion.

“It would be easy to simply remove these symbols and go on with business as usual,” Rev. Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas, the cathedral’s canon theologian and a professor at Goucher, told DCist in 2016. “We take down offending symbols all the time but never do anything about the culture that gave birth to them.”

Instead, the windows have been used as a catalyst for public discussion and programming about racial justice. “These windows—and the questions they raise—give us an extraordinary opportunity to learn more about ourselves, our collective history, and the perhaps uncomfortable places to which God is calling us,” said Cathedral Dean Reverend Randolph Marshall Hollerith at one such public conversation in October.

Now, though, the Chapter has decided the windows will be deconsecrated and removed from their place in the cathedral’s sacred space.

However, once the stained glass is conserved, they will return to the cathedral. “The desire is for the windows to find a second life as a teaching tool somewhere in the cathedral,” says Eckstrom. He says the cost of removing the windows is minimal, but creating and installing replacements will be more expensive.

The reaction to the decision is “obviously mixed,” he says. “But I’ve been struck by the people who are really happy with the decision, who finally feel that their voices are heard here, that someone is taking their experiences and the pain that they felt seriously.”

In addition to racial justice programming, the National Cathedral is auditing all its art and iconography. According to Eckstrom, that process is still underway. “We’re taking inventory of what stories are told, what stories are not told, and where we might have space in the cathedral to tell more stories,” he says.

Eckstrom says that, among those who oppose the decision, “there’s a belief out there that were just trying to forget the [Civil] War—thats just not true.” The cathedral still has other depictions of the Civil War that there are no plans to remove.

The installation of the Lee-Jackson windows followed decades of back-and-forth, and a press release in 1953 characterized it as “a move that could help obliterate the Mason Dixon line.”

Eckstrom says that the cathedral isn’t trying to get rid of depictions of slavery altogether. “The story of slavery is as old as the Bible itself,” he says. “We’re not trying to shy away from that. We’re trying to tell a story that’s more complete, more nuanced, and layered than the story that was here before.”

Previously:

National Cathedral Grapples With Stained Glass Windows Honoring Confederate Leaders

The National Cathedral Removed Confederate Flag Images With Little Fanfare

National Cathedral Taking Confederate Flag Out Of Stained Glass Windows

Rachel Kurzius

Rachel Kurzius