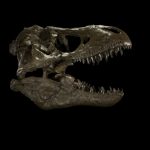

Tyee Tilghman and Caroline Stefanie Clay (Teresa Wood/Studio)

Tyee Tilghman and Caroline Stefanie Clay (Teresa Wood/Studio)

In the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump won Michigan by less than half a percentage point, along with a handful of other Rust Belt states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. This set off a still-raging conflagration of confused analysis among many liberals fretting over the plight of the near-mythical white working class, those still lingering in areas scarred by decades of globalization and driven into the orbit of Trump.

Dominique Morrisseau’s Skeleton Crew highlights a fundamental oversight in that discussion: a huge proportion of auto workers in long-suffering manufacturing strongholds like Detroit were and are black. In highlighting their stories, she paints a more coherent and disturbing picture of a slow-motion American tragedy than most with their eyes on the area care to see.

To be clear, Morrisseau is no partisan hack, and Skeleton Crew is far from an incendiary screed. In fact, it barely directly acknowledges the world beyond the break room of the circa-2008 auto plant where it takes place. That isn’t a weakness: Morrisseau cares first about her characters, and since their world revolves almost entirely around their work, so too does the world of the play.

Her script (along with the carefully detailed set design of Tim Brown) forges an intimacy with our understanding of the plant and how intertwined it is with identity of the workers even as it torments them. Their struggles as it teeters on the edge of closing aren’t just bland work troubles they can shake off after clocking out—they are central to how they exist in the world, and there is never any doubt that that existence might be imperiled for all of them.

Skeleton Crew focuses on a multi-generational group of four workers: the old hand and union rep Faye (Caroline Stefanie Clay), her younger co-workers Shanita (Shannon Dorsey) and Dez (Jason Bowen) and their foreman Reggie (Tyee Tilghman).

There’s no weak link here: their performances are uniformly stellar and bring Morriseau’s nimble verbiage and passionate intensity to life in equal measure. They’re warm and dynamic characters whose frequently hilarious banter relieves the tension when it needs to, but as the creeping dread at the heart of their circumstances starts to takes shape, their pain becomes palpable.

In a play dealing with such a fraught and current subject, it can be easy to reduce characters to a sort of exotic caricature of their social demographic, composite stand-ins for the bigger picture the playwright wants to frame. Morrisseau deftly sidesteps this. We learn about the plight of her characters as they experience it themselves, not through long-winded monologues about how they got where they are.

Faye and her coworkers exist in a world that can’t let go of the old ways of doing things but can’t let a new world be born from its ashes. United Auto Workers iconography plasters their walls and coffee cups, but the union itself is an ineffectual shell clung to only by Faye, and even then often in words more than actions.

Meanwhile, never-seen upper management imposes stricter and stricter regulations that Reggie struggles to carry out, and communal structures that might have dealt with situations like the potential closing of a plant in the past have disintegrated in favor of “every man and woman for themselves”.

This isn’t an experience unique to auto workers or the black community, but by depicting those overlooked people who exist in the intersection of the two worlds, Morriseau tells a much more effective story. Skeleton Crew is the best type of ensemble show: one that transcends its humble presentation to address an experience that exists beyond its characters.

Skeleton Crew runs through October 8 at Studio Theatre. $20-$69. Buy tickets here.