Aretha Franklin posed with her portrait in the National Portrait Gallery in 2015. (Photo by Angela Pham BFA courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

Aretha Franklin posed with her portrait in the National Portrait Gallery in 2015. (Photo by Angela Pham BFA courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

The National Portrait Gallery is displaying a portrait of Aretha Franklin from Aug. 17-22 in honor of the great American singer, who died Thursday at the age of 76.

The small portrait shows the Queen of Soul mid-song—mouth open, eyes closed. It’s beautiful, but where did it come from?

The lithographic poster dates back to 1968, a formative year for both Franklin and for the nation. In February ’68, Martin Luther King, Jr. presented Franklin with a special award from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference during one of her concerts in Detroit. She sang “Precious Lord” at his memorial service two months later.

By late summer, Franklin was the top-selling solo female artist in music history with nine top-10 hits to her name.

Not content with pop stardom alone, Franklin turned her voice into a political tool when she opened the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that August with a rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Her soulful version of the patriotic song angered many older Southern Democrats in the crowd, and highlighted the social and racial divides facing the country that the song celebrated.

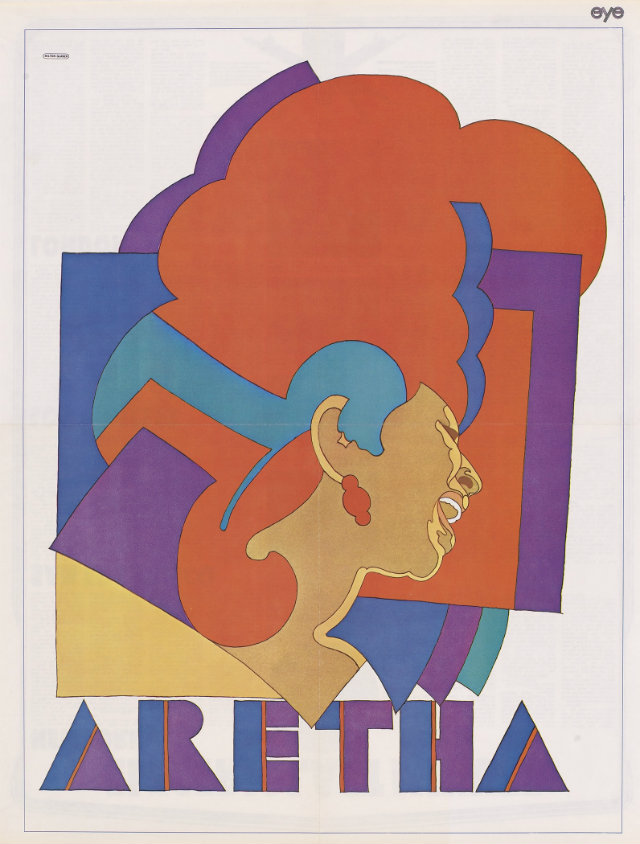

Milton Glaser’s 1968 lithographic poster of Aretha Franklin. (Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

Milton Glaser’s 1968 lithographic poster of Aretha Franklin. (Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

The poster was created by legendary graphic designer Milton Glaser, the man behind the “I Love NY” logo and the Brooklyn Brewery logo. Glaser created the poster for the November 1968 issue of the youth culture-focused Eye Magazine, published by the Hearst Corporation.

Eye only put out a total of 15 issues over its yearlong existence. The other artists featured on its poster inserts included Mick Jagger, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Bob Dylan, and the Beatles.

The Franklin poster has been reproduced millions of times over the ensuing years, but the Portrait Gallery acquired an original copy in 2011. It comes with a set of original instructions for removing it from the magazine, aimed at the magazine’s teenage readership (“tear carefully along the perforated line”).

It’s not big, either —just 25-by-25 inches — but its reds, blues, purples and golds are about as rich and multifarious as Franklin’s legendary voice was.

“It’s an important historical document,” Portrait Gallery associate curator Asma Naeem told Smithsonian Magazine. “It shows not just the incredible relevance and majesty of Aretha Franklin, at a very early point in her career, but also the incredible energy of soul music [that] has been a part of our culture for so long.”

This story originally appeared on WAMU.

Mikaela Lefrak

Mikaela Lefrak