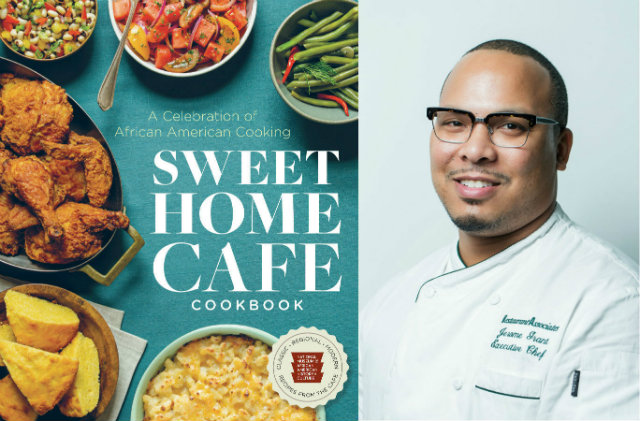

“Sweet Home Cafe Cookbook” and its co-author, Jerome Grant. (Book cover courtesy of Smithsonian Books, Grant photo by Scott Suchman)

“Sweet Home Cafe Cookbook” and its co-author, Jerome Grant. (Book cover courtesy of Smithsonian Books, Grant photo by Scott Suchman)

By DCist contributor Lenore T. Adkins

If you want really to know black Americans, you’ve got to eat their food, says Jerome Grant, executive chef of Sweet Home Café, the acclaimed restaurant at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

And with Sweet Home Café Cookbook set for an Oct. 23 release, Grant and the book’s other authors—NMAAHC supervising chef Albert Lukas and culinary leader Jessica B. Harris—have essentially written a love letter to African-American history, culture, and cuisine.

“It’s not just a cookbook … this is a book of celebration,” Grant, 36, says. “It celebrates dishes, it celebrates the history of African-American people.”

African-American cuisine represents a mashup of cultures including traditions from Africa and the Caribbean as well as influences from Native Americans, Europeans, Latinos, and recent immigrants from Africa. Two enslaved black chefs—Hercules and Old Doll—even fed George Washington.

In its more than 100 recipes, the book not only spotlights culinary links between Africans, the African diaspora, and their descendants, but it also illustrates how they adapted to their new surroundings during slavery and beyond.

For example, the book’s vegetarian Senegalese peanut soup recipe is rooted in a peanut stew called mafé, which likely got its name when Senegal was a French colony and the center of the international peanut trade, according to the cookbook.

Then there’s the Guyanese smoking hot oxtail pepper pot, Grant’s favorite recipe in the book (republished below) because it reminds him of his Jamaican grandmother. The dish of oxtail, beef, spicy peppers, and calves feet later morphed into “pepper pot” in the 19th century in Philadelphia where West Indian women served it on the streets as Philadelphia gumbo.

“We’ve been able to take almost anything and make it our own,” Grant says. “We’ve been able to take everything from those cuts of beef that people didn’t want and make great meals out of it—meals that nourished.”

Similarly, sweet potato pie, a Thanksgiving Day mainstay in numerous African-American homes, likely dates back to when sweet potatoes were the only sweets available to many Southerners, according to the book.

And Louis Armstrong’s Red Beans & Rice, named for the famous jazz trumpeter, was traditionally slow-cooked on Mondays in Armstrong’s native New Orleans because that was the traditional wash day. People needed something they could cook while they did their chores, the cookbook explains.

Other dishes, like the black-eyed pea hummus, offer a Southern spin on traditional bites.

Overall, the recipes rely less on fat, sugar, and salt and sometimes list alternative meat options to accommodate modern dietary restrictions.

So while Armstrong’s red beans and rice traditionally calls for salt pork, bacon, small ham hocks, or smoked pork butt, you can substitute chicken fat for the salt pork and corned beef or tongue for the ham hock.

“That’s just kind of how we operate as a kitchen,” Grant says of the expanded options. “We try to keep things as health-conscious as possible, but not really lose the flavor of the dish.”

The Smithsonian is launching Sweet Home Café Cookbook nearly two years after then-President Barack Obama, former President George W. Bush, and other dignitaries dedicated and opened the African American History Museum, the first national institution devoted to African-American history.

The museum, the youngest Smithsonian standing on the National Mall, has welcomed 1.4 million visitors this year as of August, according to the Smithsonian. Only five out of 21 other Smithsonian establishments posted higher numbers.

In writing the book so soon after the museum’s opening, officials are building on its popularity and buzz from its café, a 2017 James Beard Award nominee for Best New Restaurant.

They’re following the same formula they created in 2010 when Grant helmed the celebrated Mitsitam Native Foods Café at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. That’s the year the Smithsonian released “The Mitsitam Café Cookbook, a collection of 90 recipes inspired by indigenous communities.

“For us, we’ve seen great success in our cafés,” Grant says. “With the uber success that we’ve had at the African American Museum, we’re able to help drive that and do the same thing.”

Comfort-food recipes, including the ones for banana pudding, macaroni and cheese, buttermilk fried chicken, shrimp and grits, and duck and crawfish gumbo reflect cuisine the restaurant already offers that you can now try making yourself.

“This collection reminds readers of the cleverness of black home cooks who, with limited funds and often little access to a broad spectrum of ingredients, could nonetheless produce culinary masterpieces,” the introduction reads.

Sweet Home Café Cookbook, out October 23, will retail for $29.95. Jerome Grant and Albert Lukas will also discuss the book at Politics and Prose at the Wharf on October 30.

“Smoking Hot” Oxtail Pepper Pot

Recipe reprinted from Sweet Home Café Cookbook

Serves 4 to 6

Active time: 45 minutes

Total time: 5 hours, 45 minutes

This Guyanese classic is traditionally eaten on Christmas Day. Cassareep, an essential ingredient, is a molasses-like syrup made from cassava root juice. It not only gives the pepper pot its characteristic taste but also acts as a preservative, allowing the stew to cook slowly for weeks if not months. Some pepper pots are reputed to have spent decades developing flavor on the back of a stove. Pepper pot was also popular in nineteenth-century Philadelphia, where it was called Philadelphia gumbo and sold on the city streets by women of West Indian origin.

Cassareep and wiri wiri peppers, which are cherry-like in appearance, can be found in Caribbean markets or online. You may need to preorder oxtails and calf’s feet from your local butcher.

2½ pounds oxtails (thick wide part from base of tail; ask your butcher to cut into 2½- to 3-inch sections)

1½ pounds beef chuck, cut into 2-by-2-inch stew pieces

2 tablespoons kosher salt

1½ teaspoons freshly ground black pepper

½ cup brown sugar, divided

1 cup cassareep, divided

3 tablespoons vegetable oil

1 cup finely chopped yellow onion

8 garlic cloves, finely chopped

2½ pounds calf’s feet (ask your butcher to cut into 2-inch sections)

6 cinnamon sticks

2 teaspoons whole cloves

3 whole wiri wiri peppers, or 2 Scotch bonnets or habaneros

5 to 6 cups cold water, plus more if needed

4 fresh thyme sprigs

3 bay leaves

Spread the oxtails and chuck stew meat onto a sheet pan. Season the meat on all sides with the salt, black pepper, 4 tablespoons of brown sugar, and ¼ cup of cassareep. Mix well and marinate for 1 to 2 hours.

In a large stockpot, heat the vegetable oil. Add the chuck stew meat and brown well on all sides. Transfer the browned pieces to a plate. Then add the oxtails and brown them well on all sides. Remove the oxtails and transfer to a separate plate.

Add the onion and garlic to the stockpot and sauté until translucent, about 5 minutes. Add the browned oxtails, calf’s feet, cinnamon sticks, cloves, and wiri wiri peppers to the pot. Cover with the cold water just to the top of the meat.

Bring to a full boil and cook for 5 minutes, skimming off excess fat and froth. Reduce to a simmer, add half of the remaining cassareep, and cook (skimming regularly) for about 1½ hours.

At this point the oxtails should be partially tender. Add the chuck stew meat, remaining cassareep, thyme, and bay leaves and cook for another 1½ hours. During the cooking process, the water will reduce and the cassareep will thicken to a rich consistency. If at any point the stew is looking dry, add just enough additional water to keep it moist (½ to ¾ cup at a time).

Once all the meat is tender and beginning to fall from the bones, carefully remove the meat and transfer to a serving platter. Cover with plastic wrap and keep warm. Remove the wiri wiri peppers and make two small incisions in them to release more flavor and heat, then return the peppers to the sauce along with the remaining 4 tablespoons of brown sugar. Stir and briefly reduce to a rich sauce consistency, adjusting the seasoning with salt and pepper if needed.

Generously ladle the sauce over the oxtails and meat. Serve with rice.