Selfie-taking has become so prevalent in museums that many major galleries—including the Smithsonian—have resorted to banning selfie-sticks. But Brandon Fortune, chief curator and curator of painting and sculpture at the National Portrait Gallery, sees the phenomenon differently.

“I think of it not so much in terms of going to the latest spectacle, and more the way we’re recording our lives through images and self-portraits,” she says.

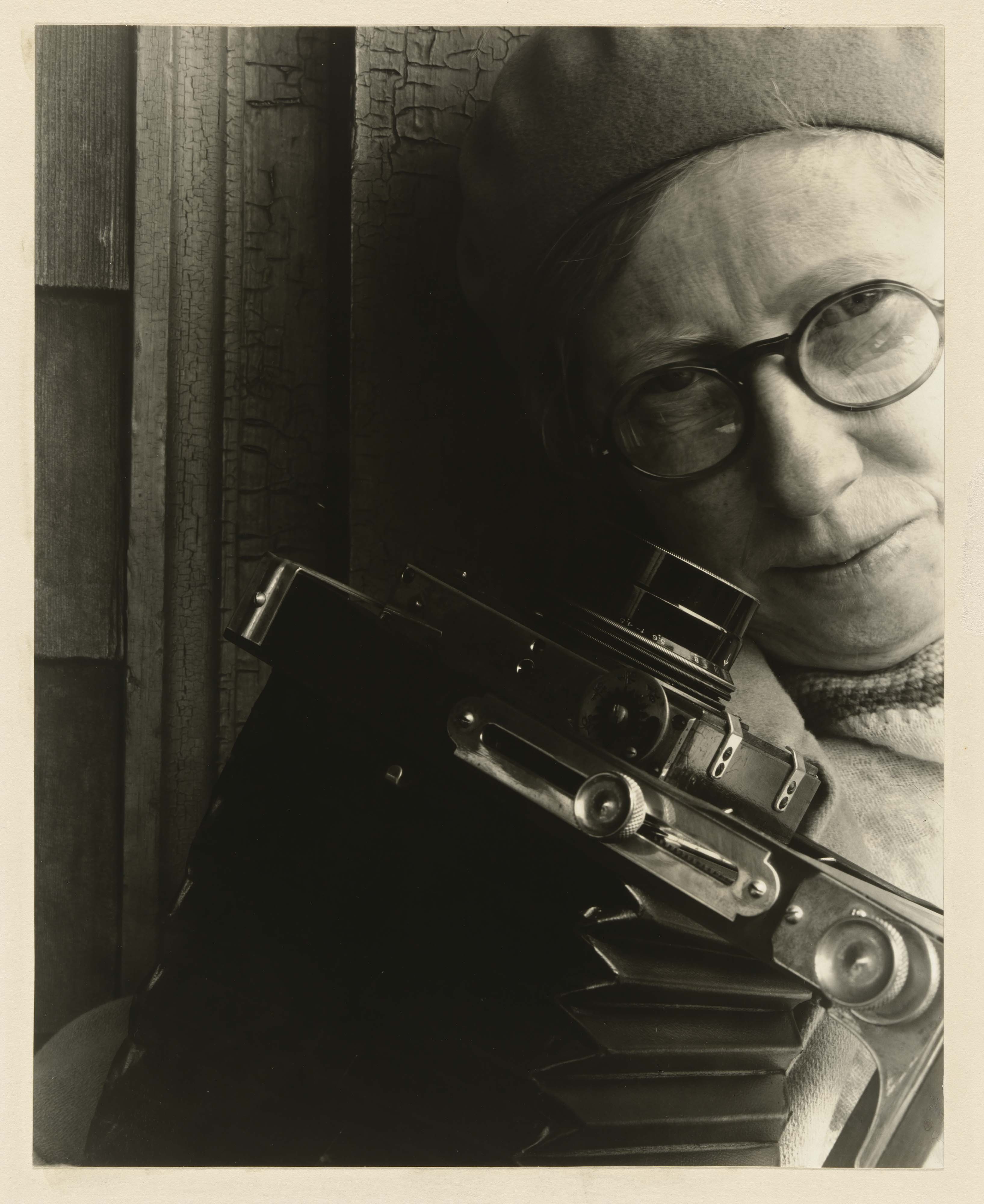

“Eye to I: Self-Portraits from 1900 to Today,” a new exhibition at the gallery, examines the artistic drive for self-reflection from the 20th century to the present.

Are today’s pixelated products of self-examination really born of the same instinct that inspired self-portraitists? Fortune thinks there is a connection.

“We are presenting ourselves as public selves all the time, and shifting and changing the way we present ourselves,” Fortune says.

That way you carefully curate the selfies in your Instagram feed has a lot in common with the way artists chose to portray themselves—and both can be deceptive.

“We may think we’re seeing some truth about the artist,” Fortune explains, ”But what we’re really seeing is what they’re presenting to us. Even if they say, as artists often do, that a self-portrait is the cheapest way to get a model, there’s always more than that going on.”

More than 75 artworks in the new exhibition illustrate this point. Ranging in size from diminutive caricatures to wall-sized photographs, and from realistic portrayals to elaborate fantasies, the artistic drive to display the self is as varied as the human experience. And in some cases, experiences that seem inherent to the social media age are actually fairly old.

For instance, consider the 1924 self-portrait by painter-muralist Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975). It’s one of the few works in the exhibition that shows the artist in a group of people According to Fortune, scholars have determined that the bare-chested artist posed himself in the manner of silent movie star Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., in the 1924 film The Thief of Bagdad. The self-portrait seems like an ancestor of the oversized movie theater lobby displays that encourage selfies with, say, Smallfoot.

But self-portraits are not all about self-aggrandizement.

In Self-Portrait with Grey Cat (2003), Native American artist Fritz Scholder depicts himself in a somber mood. Closer examination reveals why—he’s using an oxygen tank. This dark canvas was painted two years before his death.

A 1980 self-portrait by Alice Neel bravely exposes her aging body with an eye that’s unsentimental but compassionate.

Of course, self-portraits also encourage playful fantasy, as in Roger Shimomura’s 2012 lithograph Super Buddhahead. The artist and his family were placed in an internment camp in World War II, but his work breaks out of stereotypes. Here, he gives himself a Christopher Reeve-style cowlick as he imagines himself a superhero.

“We’re always presenting a persona,” says Fortune. “Artists creating self-portraits over the years have used visual art media to present a persona. To present themselves as activists, to connect themselves with certain aspects of the history of art, to create an image that seems to be very revealing and questioning. We’re doing that now with social media, and that’s fascinating to me.”

“Eye to I: Self-Portraits from 1900 to Today” is on view from November 2, 2018 through August 18, 2019 at the National Portrait Gallery. Open 11:30 a.m – 7 p.m. every day except Christmas. Free.