With Amazon officially coming to the Washington region, anxiety is mounting about one issue above all: What’s going to happen to local housing prices?

The concern is justified: The cost of living here is already a major strain on middle- and low-income residents. D.C. proper is the fourth most expensive city in North America alongside San Francisco, according to an analysis by The Economist. Nearly half of local renters and a quarter of homeowners pay more than a third of their income on housing, and 23 percent of renters are considered “severely cost burdened,” according to the Urban Institute.

Meanwhile, in Amazon’s current hometown of Seattle, the tech company created what one reporter called a “tsunami of growth,” doubling housing prices in six years and worsening homelessness in the process. So can we expect to see similar effects play out in the Washington region? Experts say it’s possible, but hardly guaranteed.

Housing is expensive here. Is Amazon going to raise prices?

The Washington region is already experiencing a serious shortage of affordable housing — both the subsidized kind and the market-rate kind. Home prices have been rising for the last eight years, especially in Arlington and D.C., according to an analysis by the Urban Institute. That’s mostly driven by sluggish housing construction and an increasingly high-income population. Local rents have also gone up since 2011, particularly in the District and Loudoun County, Virginia, according to the think tank.

If housing construction remains insufficient across the region and high-income people continue to compete for homes with lower-income people, we already have the makings of a deepening housing crisis in the Washington area. Some economists say HQ2 alone probably won’t worsen the problem by much.

“While HQ2 will generate additional demand for housing, its effects will be geographically dispersed and gradual,” says an analysis by George Mason University’s Stephen S. Fuller Institute. “Even so, the additional demand would likely increase both home sales prices and rental rates, albeit only marginally above the rise that is expected to occur without these households.”

At the D.C. Policy Center, economist Yesim Sayin Taylor puts it even more succinctly, describing the so-called “Amazon effect” as “an unimpressive flare in the region’s chronic housing crisis” — and that’s based on Amazon’s original pitch to bring 50,000 jobs here, not the current number of 25,000.

But people in the real-estate industry have a different take. Interest in Crystal City is already rising, according to real-estate company Redfin, which reported “a noticeable jump in calls, emails and tour requests from prospective homebuyers” interested in Crystal City and Amazon’s other new home, Long Island City. Meanwhile, TTR Sotheby’s International Realty CEO Mark Lowham says price increases are likely, especially in areas most appealing to Amazon workers.

“I’d be very surprised if we don’t see somewhere in the neighborhood of at least 10 percent increase in prices over the course of the next 12 to 18 months, which would be, in some submarkets, roughly twice what we are normally experiencing,” Lowham says.

Where are Amazon employees going to live?

Amazon has said its Crystal City outpost could employ 25,000 people, but those employees won’t all 1) be moving here from somewhere else 2) start working there at the same time and 3) live in one place. That means you can ignore any speculation about hoards of tech workers suddenly overwhelming your favorite local bar. (Unless that bar is located in Crystal City and you go during happy hour sometime after 2019, when Amazon is expected to start hiring.)

Amazon has said its Crystal City outpost could employ 25,000 people, but those employees won’t all 1) be moving here from somewhere else 2) start working there at the same time and 3) live in one place. That means you can ignore any speculation about hoards of tech workers suddenly overwhelming your favorite local bar. (Unless that bar is located in Crystal City and you go during happy hour sometime after 2019, when Amazon is expected to start hiring.)

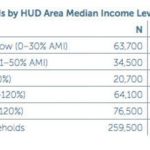

But many Northern Virginia Amazon workers are likely to gradually settle down in the Washington region, with most located in Fairfax, Arlington, D.C. and Montgomery County, in that order, according to the Fuller Institute — depending on how well those jurisdictions’ housing markets respond to demand. If developers are able to start building lots of new, transit-accessible housing over the next several years, local jurisdictions could theoretically meet current and future demand, including any generated by Amazon. But that’s a big “if.”

“Our development pipeline is relatively fixed,” says Mark Lowham at Sotheby’s.

Land in D.C. and the immediate suburbs is also restrictively zoned, which combined with high land and construction costs has dampened the pace of growth overall. That’s why smart-growth advocates say allowing more density through upzoning — followed by multifamily construction near transit — could help reduce pressure on prices. (Conveniently, that type of urban-style housing is also likely to attract young, unmarried, high-income Amazon workers.)

So… is now the right time for me to buy or sell a house in the D.C. area?

If you’re been sitting on the sidelines waiting to buy a place — and you have the money — now is the time to make an offer, Lowham says. Even though Amazon is unlikely to generate widespread, hefty price increases, it’s always safer to judge based on current market conditions.

“There is a little bit less uncertainty today than there will be in 12 months,” Lowham says. “This is probably the right time to step into the market.”

If you’re waiting to sell, he says, keep in mind it’s always a good time to sell in the Washington region — especially if your home is located near transit. But sellers in Northern Virginia, in particular, might want to wait to put their homes on the market. That’s because Amazon is projected to create thousands of jobs per year starting in 2020, with most new jobs expected to arrive in 2023, 2027 and 2028, and it’s possible some corners of the market will see higher demand because of that.

Then again, it’s tough to say what the local housing market will look like in 12 months, let alone 10 years.

“It’s very hard to forecast what the opportunity set is going to be,” Lowham says. “We’re encouraging our clients to make informed decisions today based on the best advice we can give them in the current market. Beyond that, we’re all just speculating.”

This story originally appeared on WAMU.

Ally Schweitzer

Ally Schweitzer