Sandwiched north of the Anacostia River and south of the U.S. Capitol, Navy Yard earns media attention most often for its ballpark, where the Washington Nationals strive each year for an elusive spot in the World Series. More recently, the Ward 6 neighborhood has been in the news for its new Whole Foods, which is upscale even by Whole Foods standards. Readers may also recall a much-discussed Politico article that named Navy Yard’s ritzier residential buildings as home to many low-level employees of the Trump administration. It described a sequestered waterfront neighborhood in which “young Trump staffers mix largely with each other and enjoy the view from their rooftop pools, where they can feel far away from the District’s locals and the rest of its political class.” But the neighborhood is much more than a playground for political staffers. In the latest installment of our neighborhood history series, we’re taking you beyond the ballpark, beyond the travails of Trump staffers, for a look at what else is hidden around the area.

1. Some neighborhood leaders don’t love the name “Navy Yard”

The neighborhood derives its name from the federal facility established in the late 18th century, now diminished from its heyday as the nation’s shipbuilding hub. The facility counted Abraham Lincoln among frequent visitors, and John Wilkes Booth escaped over the Navy Yard bridge after fleeing Ford’s Theatre on the night he assassinated the president. Today, the Navy Yard serves as an administrative and ceremonial center for the U.S. Navy—an office park with a rich history. In 2013, the neighborhood made the worst kind of national news for a fatal mass shooting inside the facility.

But while the surrounding neighborhood is most commonly referred to as Navy Yard, the local Business Improvement District has for the past decade used “Capitol Riverfront” on marketing materials and at local events, according to Bonnie Trein, the organization’s marketing and communications director.

“The Capitol Riverfront brand speaks to this entire 500-acre area and also increases search engine optimization—we’ve seen from keyword reports that people search ‘what to do along the river’ or ‘things to do near the Capitol’ than they do ‘Washington Navy Yard,’” Trein told DCist via email.

Trein knows the Navy Yard can’t be avoided, in part because that is how it’s identified by the area’s Metro station. But the BID thinks and hopes “Capitol Riverfront” will attract more residents and visitors. For consistency’s sake, we’ll continue to call it Navy Yard for the rest of this article.

2. The Blue Castle at 8th and M does more than just look pretty

The fanciful Romanesque structure dates to the 1890s, when architect Walter C. Root designed it as a repair facility for the Washington and Georgetown Railroad. (Yes, you read that right! An entire mode of transportation—first horse-drawn vehicles and later cable cars—was designated for a neighborhood that now famously lacks a dedicated Metro station. The 20th century was wild.)

Eventually, the building became a storage facility for the line’s cable cars, during which it became known as the Navy Yard Car Barn. Once that iteration of the streetcar stopped running, the building became a facility for several local charter schools.

The castle has skirted redevelopment at least once. In 2005, a developer announced plans to convert the building for retail use, along the lines of a Barnes & Noble or a Whole Foods. Similar ideas came up when developer Madison Marquette purchased the building in the early 2010s and business types primed the nearby Barracks Row for a resurgence.

But in 2014, the National Community Church bought the building for more than $25 million with the help of a $4.5 million donation from one of its parishioners. It’s taken a while, but the church finally unveiled plans earlier this year to redevelop the building in stages. In its final form, the new facility will boast a 900-seat auditorium for Sunday services and a daycare center.

But what of the blue, you ask? Shortly after the sale, lead pastor Mark Batterson told neighborhood blogger JD Land to expect some aesthetic changes, provided that historic preservation rules don’t get in the way.

“Honestly, we hope that someday the Blue Castle will just be the Castle,” Batterson said.

The Blue Castle is located at 770 M Street SE

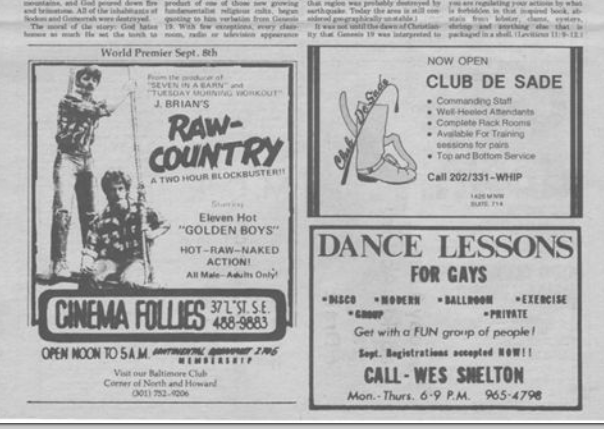

3. The District’s gay community considered Navy Yard an enclave in the 1970s.

A new entertainment district sprang up in the Navy Yard as a generation of gay residents began to come out and seek a community. Between South Capitol and First streets in particular, nightclubs, bathhouses, “adult entertainment” movie theaters, and strip clubs dotted the landscape. That location had previously been home to a middle-class African American community, but riots in the late 1960s left much of the area burned and boarded up.

One adult theater, Cinema Follies at 37 L St. SE, was the site of a devastating fire in 1977 that killed nine people. Several of the victims couldn’t be identified because many people in the gay community at that time avoided carrying ID cards in public spaces (Cinema Follies was a frequent target of D.C. police).

Many of the LGBTQ bars in the neighborhood closed in the 1980s amid the AIDS crisis. Meanwhile, the Barracks Row Business Alliance formed to revitalize the neighborhood, in the process squeezing out some of the small businesses that had remained from earlier eras.

The Cinema Follies building, though severely damaged, managed to stay standing for four more decades, eventually serving as an office for a cab company until being torn down last year. Follies, meanwhile, eventually reopened at 24 O St. SE, but it was demolished in 2006, along with numerous other gay venues in the area, to make way for Nationals Park.

4. Beneath Virginia Avenue lies a 19th-century tunnel

In 1872, the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad built a two-track tunnel below ground between 15th and M streets SE to 2nd Street and Virginia Avenue SE. The tunnel originally serviced a railroad station located at the current downtown site of the National Gallery of Art. Both passengers and freight passed through until Union Station opened in 1908, at which point the tunnel only permitted freight to pass through. Close to three decades later, the railroad company removed the second track to make way for larger vehicles—a move they would eventually reverse decades later.

CSX has spent the last three years rebuilding the tunnel infrastructure and turning it into two tunnels, addressing structural concerns and accommodating double-stacked freight cars and two-way train travel. Nearby residents raised concerns about environmental impacts and noise before the project was set in motion and have continued to agitate during construction. Earlier this year, construction officials announced that relief is on the way.

5. There’s a museum open to the public (with a little effort) within the Navy Yard military base

Even longtime residents might consider the National Museum of the U.S. Navy off the beaten path—so much so that the Washington Post Express recently described it as “D.C.’s secret Navy museum.”

Indeed, security at the naval facility has tightened over the years, especially in light of the tragic 2013 shooting. According to the Express, visitors’ first sight upon arrival is a sign that reads “Warning, This Property Patrolled by Police Dog Teams.” It’s not exactly a warm welcome.

Once inside, though, the museum has a ton to offer, not to mention light crowds and a more relaxed atmosphere than the Smithsonian venues. Vehicles, weapons, and equipment provide a glimpse at the country’s military history and an opportunity to reflect on the evolution of combat.

Weekday visitors without a military ID should plan ahead for a 20-minute background check at the Visitor Control Center. That office is closed on weekends, so Saturday and Sunday visitors need to submit a request for access online or by phone two weeks in advance. More details here.

National Museum of the U.S. Navy is located at 736 Sicard St SE.

6. The entire Navy Yard complex was burned down (by Americans!) during the War of 1812.

When the British broke through American military barriers in D.C. in the late summer of 1814, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy ordered the Yard’s commander Thomas Tingey to set fire to the yard, and to three large ships that were in various stages of completion. The goal was to prevent crucial American hardware from falling into British hands. (U.S. officials had previously assumed the British wouldn’t want to penetrate the relatively sparsely inhabited D.C.)

The Navy secretary didn’t call for entirely scorched earth. In fact, he recommended that Tingey salvage as much gunpowder as he could. But much of his militia was otherwise occupied at the time and couldn’t devote the manpower to transporting delicate cargo.

Tingey had spent the last decade and a half overseeing the construction of the yard, so he wasn’t eager to bid it farewell in such devastating fashion. He waited to give the burning order until the last possible moment, hoping his militia could beat back the British. But eventually he had no choice, lighting powder trains that had been spread across the whole facility. He headed off to Alexandria in a small convoy of ships, leaving the burning wreckage of his professional accomplishments in his shadow.

7. One of the city’s main waste thoroughfares runs through the neighborhood.

Prior to 1889, open sewers carrying the city’s waste were deposited directly into the Potomac River. For some reason, the president of the United States thought there might be a better solution, so he appointed a working group to come up with an alternative plan. (So, you know, we’ve made some progress as a species since then.)

That group’s efforts resulted in the steel and red brick O Street Pumping Station, built between 1904 and 1907 at 2nd and O streets SE, where the C&O Canal and the Anacostia River met. Construction coincided with the “City Beautiful” movement at the time, which included the installation of urban parks and the erection of the Connecticut Avenue bridge over Rock Creek Park.

If the building, still in use for the same purpose today, bears a resemblance to Union Station, that’s no accident—both were built in the Beaux Arts style, popular at the time for symbolizing “wealth, beauty and civic pride.”

8. The giant steel sculpture on New Jersey Avenue SE is wind-powered

Tear yourself away from that mesmerizing video for a few seconds to learn that this sculpture by the prolific artist Anthony Howe currently dazzles passerby on New Jersey Avenue SE near H Street SE. The piece, entitled Shindahiku/Fern Pull, consists of 18 balanced wings rotating around a circular axle. The Capitol Riverfront BID and developer W.C. Smith purchased the sculpture earlier this year; it first appeared in the neighborhood in August.

Howe has been working on projects like this for more than two decades, inspired by his former part-time occupation of building steel shelves for office storage. His work his appeared all over the world, including at the opening ceremony of the Rio Olympics and behind a performance of “How Far I’ll Go” from Moana during the 2017 Oscars.

9. Navy Yard has its very own unofficial neighborhood historian.

Nearly two decades ago, Jacqueline Dupree took some photos of the neighborhood surrounding her home, which lies just north of the Southeast Freeway. A few years later, more than a year before the city announced that Nationals stadium would be descending upon her neck of the woods, Dupree started snapping photo after photo and posting them to a humble blog.

“As it became clear that the neighborhood two blocks to my south was going to undergo a huge transformation, I knew I wanted to document the changes,” Dupree writes in her online bio.

That site has become JDLand.com, a treasure trove of photos, historical facts and news developments that keeps Navy Yard history alive in far greater depth than any other local media outlet could hope to accomplish (indeed, some of this article’s contents drew from Dupree’s archive). As of 2016, her site was attracting an average of 12,000 hits each week.

Dupree has a full-time job at the Washington Post, where she designed the publication’s internal website and works on other technical projects. JDLand was a domain name she reserved in 1996 long before she had the idea for the site. Though she abandoned her intended journalism major in college because she despised covering public meetings, she’s gradually taken on more original reporting, keeping residents informed about what’s happening outside their doors.

This May, she announced that she was pulling back from daily updates on the neighborhood goings-on. “It might be that, after 15 years, I have reached my maximum allowable limit of words written about zoning, public meetings, ribbon cuttings, retail spaces, project delays, and expected opening dates of highly anticipated grocery stores,” she wrote, though pledged to continue taking photographs and “maintaining the project pages, maps, sliders, and whatnot, because it’s not like I won’t be watching.”

10. There’s a leg…buried in a parking garage…(that may or not still be there).

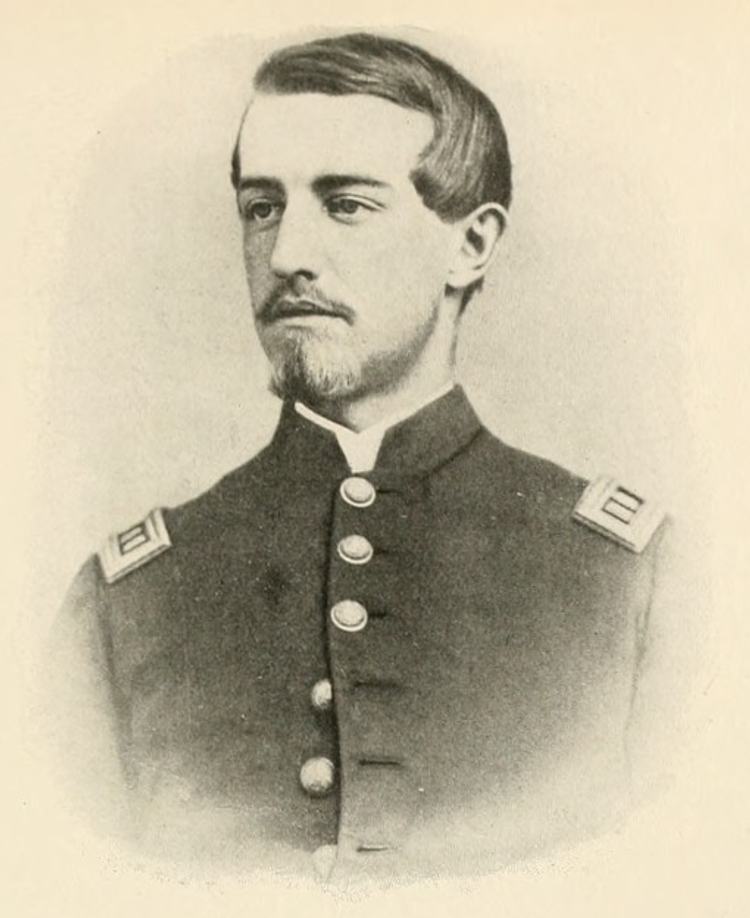

The severed appendage in question belongs to Col. Ulric Dalhgren, who fought in the Civil War. In 1963, he was amid post-Gettysburg combat on the streets of Hagerstown, Maryland, when his right foot and lower leg got hit by a bullet. Dahlgren’s leg was eventually amputated below the knee, but he survived after a few shaky days. A year later, Dalhgren died during a Richmond raid targeting Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

If I were to lose my leg tomorrow, I’m willing to bet it wouldn’t end up buried in a parking garage and marked with a commemorative plaque. But Dahlgren benefited from nepotism—his father was Rear Admiral John Dahlgren, who developed an innovative “smooth-bore cannon” and earned the admiration of Abraham Lincoln.

As it turns out, leg burials weren’t uncommon back then, at least for the well-connected, according to the blog Ghosts of DC (a virtual treasure chest of historic ephemera). The sweltering D.C. summer heat kept Dahlgren from burying the leg at his home, so it instead ended up in the cornerstone of a new foundry building that was under construction at the time. That building has since been torn down and replaced several times, but a plaque in the Navy Yard’s Building 28, now a parking structure, keeps Dahlgren’s memory alive.

His leg, on the other hand, is another matter entirely. A Washington Post report from 1991 indicates Dahlgren’s leg might have been moved at some point, and that the plaque may not necessarily pinpoint the exact spot where Dahlgren’s leg ended up. Is there a leg heist afoot? If so, that might be the most fun fact of all.

BONUS: Want more? There’s a movie for that.

The 2007 documentary Chocolate City offers a stark portrait of gentrification’s effects through the eyes of residents (including local legend Mrs. Frazier) of the Arthur Capper/Carrollsburg housing projects in Southeast. The movie is available for free on YouTube, and DCist wrote about it when it came out.

Previously:

10 Facts You May Not Know About Brookland

Ten Facts You May Not Know About Anacostia

Ten Facts You May Not Know About Dupont Circle

Nine Facts You May Not Know About The Southwest Waterfront

This story has been updated to correct the account of Booth’s escape via the Navy Yard bridge.