The impact of a government shutdown can be measured in a number ways: Lost wages, lost productivity, canceled government contracts and services.

What’s harder to measure, but perhaps more consequential in the long run, is the shutdown’s effect on the federal government’s ability to recruit — and retain — top-level talent.

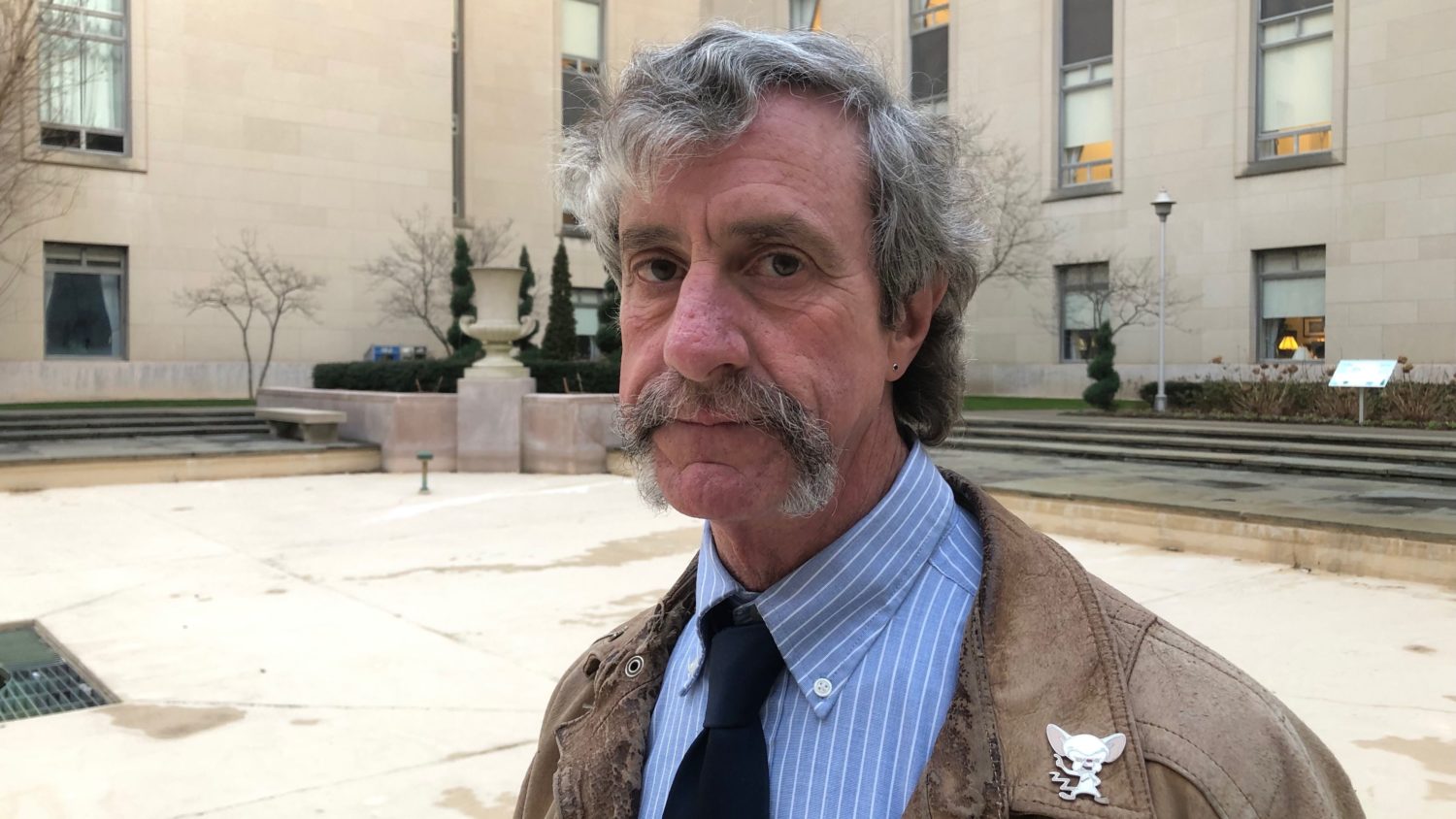

Take Paul Greenberg, a research physicist at NASA.

He’s probably a genius.

He’s definitely a character.

He’s got long hair and a handlebar mustache. His frayed leather jacket has two pins: one is from the cartoon Pinky and The Brain, a show about a genius mouse; the other is of a replica 1913 BMW motorcycle.

“I ride with the Shul Boys, which is the largest international chapter of Jewish motorcycle riders,” Greenberg said.

This motorcycle-riding rocket scientist from NASA also has worked on some seriously fascinating — and mission-critical — government projects during his nearly 30 years at the space agency.

“I was the first person to measure the nanoparticle content of lunar soil,” Greenberg said.

“I worked on fire detection for spacecraft,” he said, noting that “having a fire in space is not a good thing.”

He added, “I’m building optics for the next generation of deep space communication. We just went to the edge of the galaxy.”

Even his non-space-related-work is mind-blowing: he’s building a handheld monitor for first-responders that lets them measure the levels of hazardous material in the air.

‘It’ll Take Years To Reset This’

When asked about the effect of the government shutdown on federal agencies like NASA, Greenberg took a deep breath, and calmly explained that space exploration and government shutdowns — well, they simply do not go together.

“Everything in space flight is coordinated to the minute: what has to be done when, the reviews, the testing, the crew training,” Greenberg said. “And when you throw a five-week wrench into that — it’ll take years to reset this.”

That’s just one program. Across NASA and dozens of other federal agencies and departments, critical studies, tests and other programs were disrupted by the five-week shutdown.

Of course, the recent shutdown also affected many of these employees personally — their finances, their sense of well-being.

Why would the political leadership treat its workers like this, Greenberg wondered. Don’t they appreciate what they do?

“Like, is some loser gonna put a rover on the moon? I mean come on!” Greenberg joked.

‘This Is Frontline National Security.”

Here’s the thing about NASA and folks like Greenberg, or any of the other skilled engineers, scientists, lawyers and software developers that ply their trade across the federal government: They could make a lot more money working in the private sector. They choose to work at the federal government because of the mission — and for its stability.

But federal workers have breaking points.

“People are leaving. We lose people,” Greenberg said, who also works as a union representative at his NASA facility in Cleveland, Ohio.

He tells the story of a cybersecurity specialist at NASA who left during a government shutdown.

“Best [security specialist] in the world,” said Greenberg, noting that NASA is the country’s most-hacked federal agency. “[Then the] government shuts down. His wife says you have a family. Hasta la vista. He walks across the street to Google at twice the salary. He’s gone.”

“This is not just intellectual capability and continuity,” Greenberg adds. “This is frontline national security.”

‘The Equivalent Of Burning Down Your Own House’

For someone like Max Stier, who leads the Partnership for Public Service, a nonprofit devoted to revitalizing the federal workforce, it’s hard to put into words how bad this latest shutdown was.

“It really is the equivalent of burning down your own house,” Stier said. “We’re gonna have lots of great people leave because of what happened, and we’re chasing away the next generation of talent that’s vital to the health of our government.”

For years, Stier has led the effort to modernize the federal workforce, including fixing outdated hiring laws, recruiting skilled young people and replacing those set to retire.

But right now, his focus is on preventing another shutdown.

“There should be a Geneva Convention that says in partisan battles you can’t threaten the operations of our government,” says Stier. “You can’t denigrate the public service workforce. These are things that are off limits.”

‘On What Planet Would It Make Sense To Vilify Your Employees?’

There’s no accurate count yet of how many federal workers left the government because of the shutdown.

Several prominent job-seeking websites reported a heavy uptick in searches from employees at the unfunded federal agencies.

At a NASA town hall just days after the government reopened, Jim Bridenstine, the head of the space agency, reported that while there was no “exodus” of workers, a handful had quit.

Nearly every employee at NASA was furloughed during the shutdown. Now with another potential shutdown looming, Greenberg, the research physicist, is stunned that it might happen again.

“For God’s sakes, we are the employees of the American taxpayer,” he said, exasperated.

“On what planet would it make sense to vilify your employees or not want the best people to be your employees?” Greenberg asks.

It’s a question this rocket scientist still can’t wrap his mind around.