On March 3, 1913, more than 5,000 women in ankle-length dresses and coats brought their picket signs and shouting voices to Washington. They were there for the Woman Suffrage Parade, and their goal was to attract media attention for their cause: securing the right to vote for women.

Demonstrations are common occurrences on the National Mall these days. But back then, it was essentially unprecedented. (The only previous event of its kind was in 1894, when a group of unemployed workers called Coxey’s Army marched on Washington). It took some time, but the suffragists eventually succeeded. Congress passed the 19th Amendment in 1919 and it was ratified by all states by the following year.

In advance of the amendment’s centennial anniversary, the National Portrait Gallery is opening “Votes For Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” an exhibition that explores the decades-long history of women’s suffrage in the United States.

It’s a fraught history to tell. The successes of the suffrage movement are stained with racism and classism. African American women were consistently sidelined by white suffragists, and black women in Southern states faced serious obstacles to voting through the mid-1960s.

The exhibition’s curator, historian Kate Clarke Lemay, did not shy away from this history. The exhibition highlights a number of African American women suffragists, many of whom also played important roles in D.C. history.

“There were lots and lots of different people working on suffrage,” she said. “I find that really exciting, and I’m pretty sure that other people are going to find it exciting, too.”

Take Anna J. Cooper and Mary E. Church Terrell, two turn-of-the-century African American suffragists whose portraits are featured in the exhibition. Both women went on to teach at M Street High School (now Dunbar High School) in D.C., the city’s first public high school for black students. Cooper became principal in 1901.

The exhibition is peppered with interesting stories about D.C. history, too. According to Lemay, suffragists were responsible for the growth of one of the most Washington of industries: lobbying.

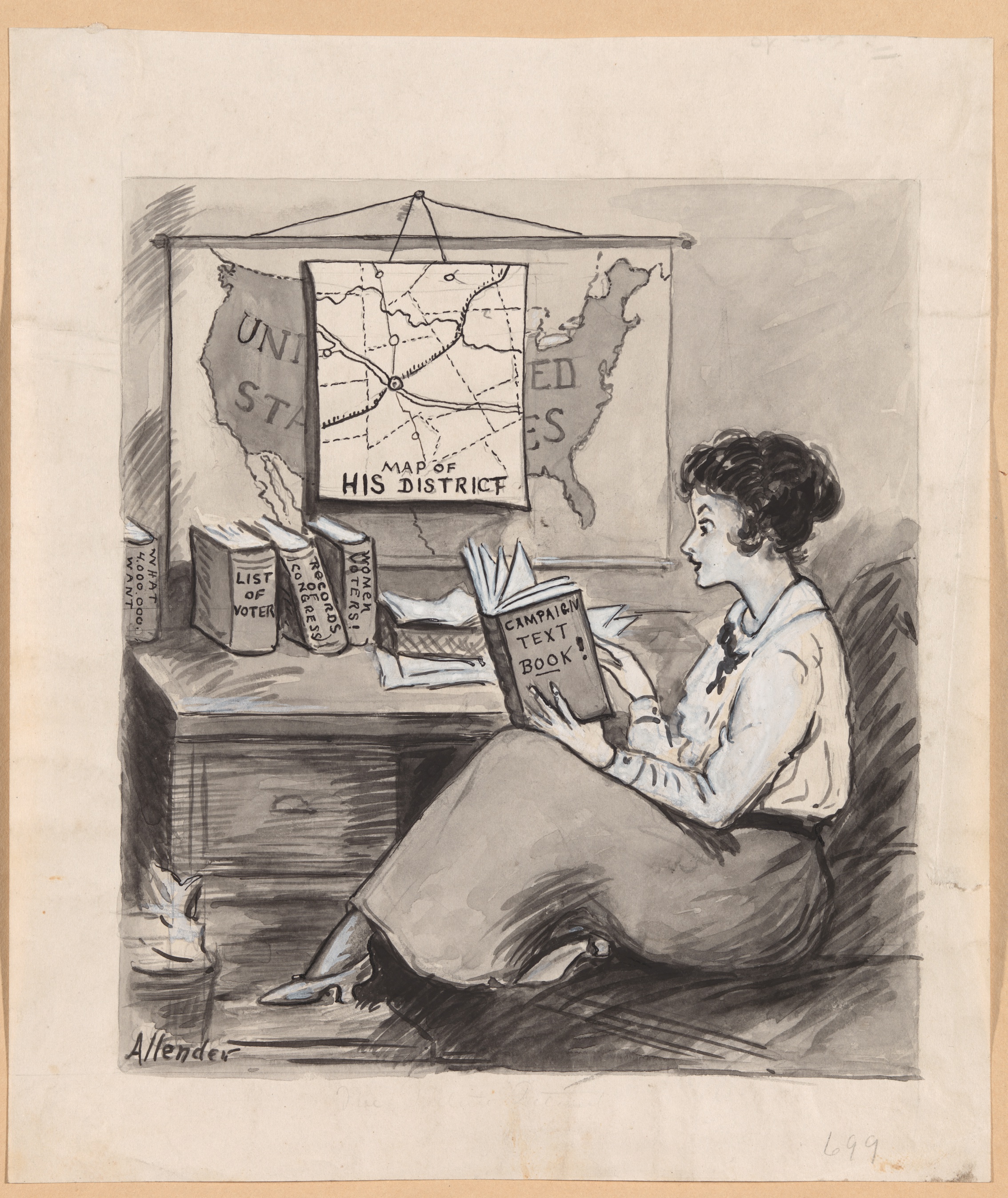

In this 1916 charcoal drawing called “His District,” a woman researches a Congressional representative so she can lobby him to support women’s suffrage.Nina E. Allender / National Woman’s Party

“It’s thanks to American women suffragists that we have the lobbying system today. They’d go out and research an area’s representative [to Congress] and then try to persuade him to endorse suffrage for women.”

Women also routinely got themselves arrested while protesting President Woodrow Wilson’s unwillingness to support suffrage. They were imprisoned in Lorton, Virginia and used the experience to their advantage. Photographs of the women in jail and news of their hunger strikes drew attention to their cause.

The exhibition is part of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative “Because Of Her Story.” Its goal is to better research, collect, and display women’s stories. The Smithsonian and other major museums have faced repeated criticism for overemphasizing art by and about men.

“Votes For Women” helps tips those scales. One hallway in the gallery is now filled entirely with portraits of women — a rarity for the gallery.

“Badly behaved women rarely got their portrait done,” said museum director Kim Sajet. Nevertheless, these badly behaved women found their way in.

This story was originally published on WAMU.

Mikaela Lefrak

Mikaela Lefrak