For the first time in more than a month, Laurel-based Sudanese American poet and community organizer Bayadir Mohamed-Osman was able to contact her aunt in Sudan on Tuesday morning. She was in the car when she got the message via WhatsApp, which read “at last.” When Mohamed-Osman saw it, she began to cry.

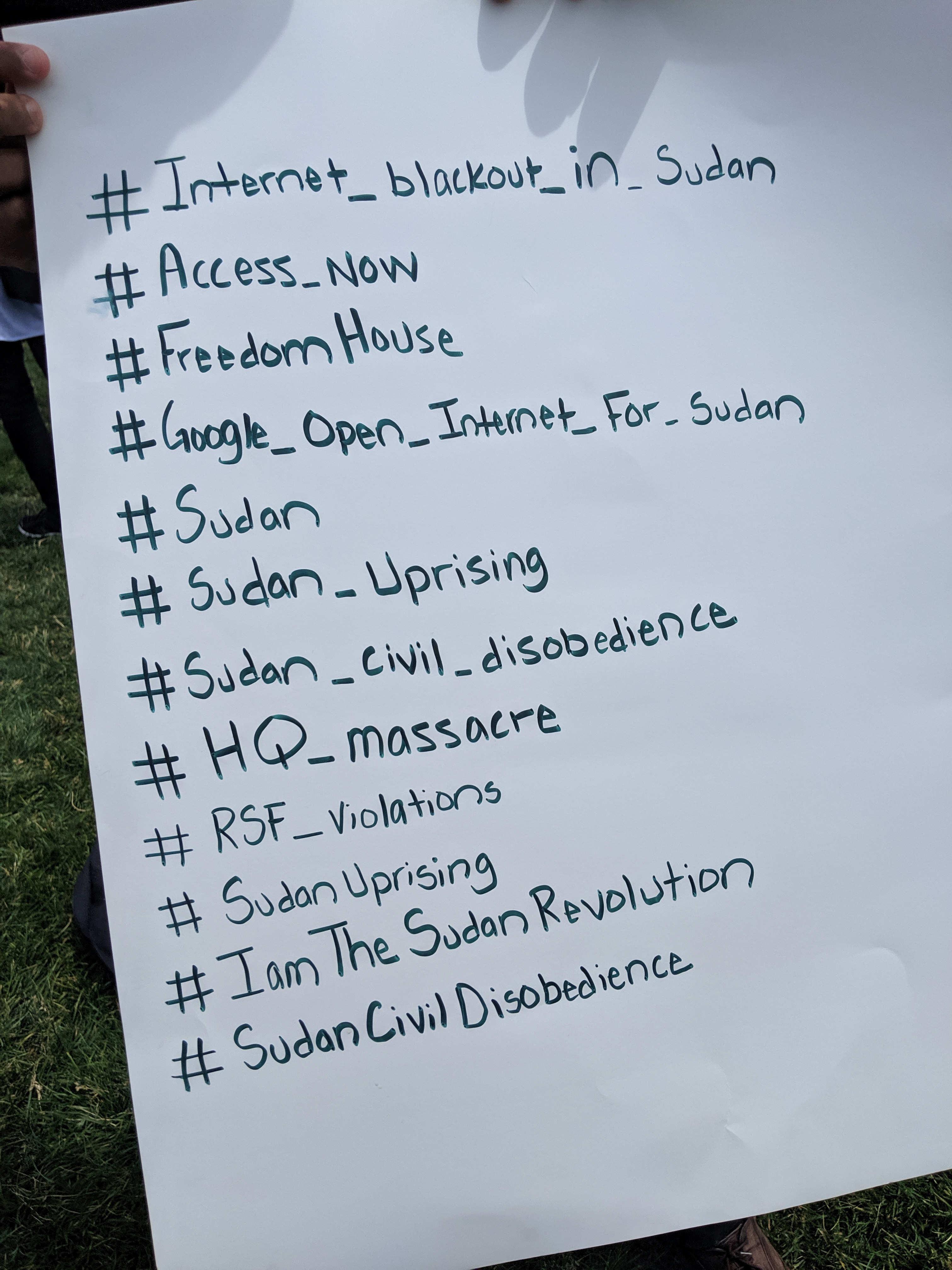

Like many Sudanese people in the D.C. area, she has been unsuccessfully trying to contact family and friends in Sudan for much of the past month due to a government-imposed internet blackout in the country. Earlier this week, the internet was turned back on in some parts of Sudan, according to activists.

Sudanese authorities began restricting social media sites like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter at the end of December 2018 in response to growing anti-government protests. But despite the restrictions, activists on the ground at first found a way to broadcast the uprising via social media by using virtual private networks. Through platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter and messaging applications like WhatsApp, Sudanese people living outside the country, including Mohamed-Osman and others, have been able to closely follow the protests.

Mohamed-Osman wrote in a poem last month: “Twitter has become an obituary, WhatsApp a newsroom. Lives ending on Facebook Live.”

But in early June, when the Internet went completely dark on the heels of a violent crackdown on protesters by paramilitary troops, even that option was no longer working.

Since gaining independence from British colonial rule in 1956, Sudan has seen decades of corruption, economic mismanagement, and the ongoing mass slaughter of civilians in the western and southern parts of the country.

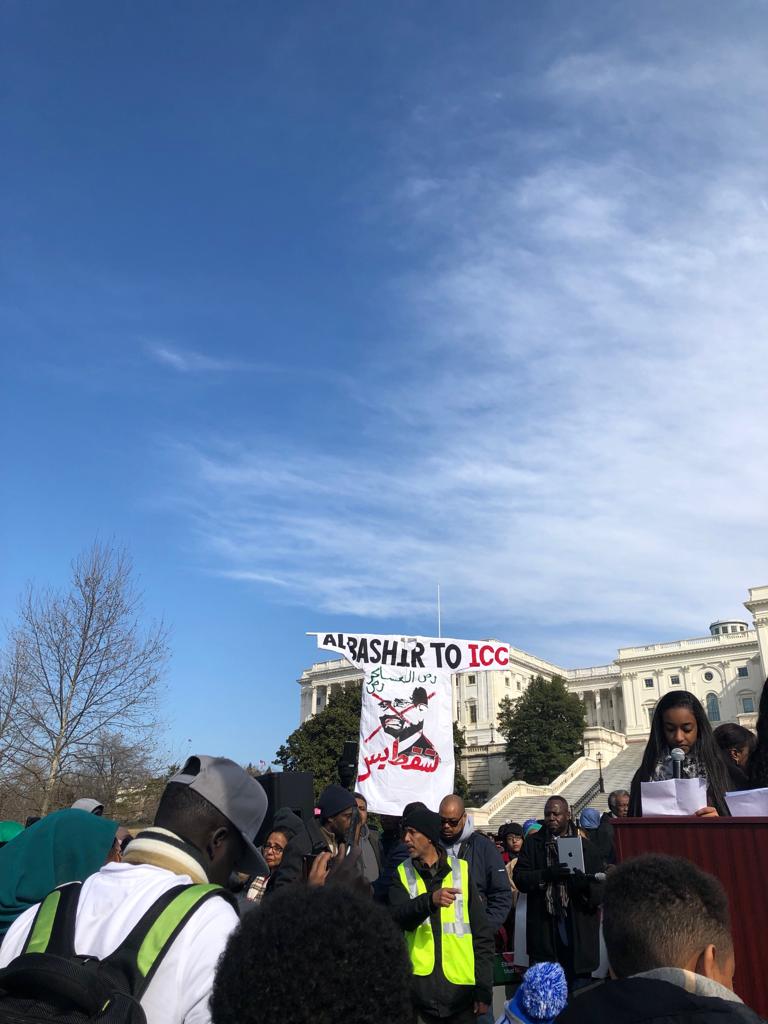

In December 2018, protests spread throughout the country. Initially sparked by a rapid rise in the cost of bread and other basic commodities, the protesters soon began calling for an end to President Omar Al-Bashir’s almost 30-year reign, demanding a democratically elected, civilian-led government in his place. Al-Bashir was ousted in April, and was soon replaced by military officials.

The small but bustling Sudanese community in the D.C. area has been closely following these developments. The east African nation is among the top 10 countries whose nationals immigrate to the region, according to the Population Reference Bureau. (This figure doesn’t necessarily account for second or third-generation Sudanese Americans who were born in the region.)

Ahmed Kodouda, a graduate student at George Washington University, says that while the community is small, people are well connected and have strong ties to one another. There are a handful of community organizations, like the Sudanese American Community Development Organization and the youth-focused Moving Forward Sudan, that regularly organize events for the community, including cookouts, Eid prayers, Ramadan iftars, and networking sessions.

Kodouda says that the events in Sudan have mobilized the community in ways that he hasn’t necessarily seen before. “I think people are channeling their grief into energy to help the civil resistance and the peaceful mobilization against the regime,” he says.

That observation mirrors Chantilly pediatrician Sulaf Lutfi’s experience. Prior to the protests in December, Lutfi was not very involved with the community, but that quickly changed. “I hated politics, I had nothing to do with politics prior to December,” she says. “All it took was that first bullet that ended up in a kid’s head to get me going.”

After the protests in Sudan began at the end of last year, Lutfi was one of many in the community who formed organizations and coalitions to support the protesters on the ground. These new groups, in addition to organizations that have long had a presence in the community, have put on a handful of marches, rallies, panels, and advocacy efforts in support of the uprising.

But the events in Sudan haven’t just changed the way that some Sudanese Americans are engaging with the world around them. They have also changed how some of the community is engaging with itself and reckoning with some of the more unfavorable parts of the country’s history and culture.

For American University graduate Dau Doldol, the bloody videos and photos that poured out of Sudan have been painful to witness, but in a different way.

Doldol, whose family is from the Abeyi region of Sudan, a disputed area squeezed between the border of Sudan and what’s now South Sudan, says the videos reminded him of the violence and trauma that his family experienced during Sudan’s second civil war.

“Everything that’s happening now is sometimes a mirror image of what I experienced, and it brings back deep trauma of the things that I went through, the things that my family experienced,” he says.

Doldol says that most people in the Sudanese diaspora don’t know the extent of the atrocities that have been occurring in areas outside of the capital, but for him, the sort of violence that broke out last month is nothing new. “This is the Sudan that I’ve always known, this is the Sudan that those on the periphery have always known,” he says.

Last week, civilian representatives and military officials struck a deal establishing a joint sovereign council that will share power for a little over three years, until elections are held. Many are celebrating the announcement and protest leaders in Sudan have cancelled a march planned for later this month.

The news of the deal brings mixed feelings for Mohamed-Osman, as it does for some activists on the ground. She is happy an agreement was reached but at the same time, is watching closely how things unfold, ready to continue organizing solidarity protests in the D.C. area should the situation in Sudan take a turn.

In the meantime, she’s keeping her social media profile photo the demure shade of blue that’s come to symbolize the Sudanese uprising.

This story has been updated to reflect the accurate spelling of Sulaf Lutfi’s name.