For the last 35 years, hundreds of cars each day have driven past Rosslyn’s Dark Star Park and its five concrete spheres. This tiny parcel of land dotted with Death Star-resembling sculptures, pools of water, cement tunnels, and steel poles are just a part of the commuting landscape for many. But this Arlington park is much more than just something to drive by and walk through. It is one of the region’s most significant works of public art from one of the country’s greatest land artists, Nancy Holt.

And every year on August 1 at 9:32 in the morning, the spheres and sun converge, creating a show of shadows unlike anything elsewhere. The shadows align with a series of matching metal shapes on the ground, creating an almost eclipse effect. Then, in a matter of moments, the shadowy spectacle moves on.

“To tell someone that you’ve got to go to this traffic island in the middle of Rosslyn, it doesn’t sound like a very attractive prospect,” says Lisa Le Feuvre, the executive director of the Holt/Smithson Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to the work of Holt and her artist husband, Robert Smithson. “But when you do, you find that time stops and everything slows down.”

This August 1, Arlington Arts will join the Hirshhorn Museum in celebrating the 35th anniversary of this seminal work of public art. On Wednesday and Thursday, the Hirshhorn will host screenings and public discussions about Holt, her work, and the impact she left as a pioneer in land art. On the day of the alignment, local duo and recording artists Janel and Anthony will premiere their original site-specific composition while the sun, shadows, and spheres get ready to align.

It’s a lot of fanfare in an area that was a much different place in the late 1970s. Despite significant development in the previous decade, the Arlington bedroom community was still very much in transition. I-66 was still under construction. The Metro station had just opened. The federal government was battling against the building of high-rises. There were still seedy-looking motels and bars. And, in June 1979, rock star Lowell George died here. Rosslyn was in much need of a cultural touchstone.

“We had some very enlightened leadership [back then],” says Angela Adams, Arlington’s director of public art. “They had this idea of introducing large-scale sculpture as a way of … creating a symbol for our community.” With contributions from a National Endowment of the Arts grant, the county pooled $200,000 from public and private sources to build Arlington’s first piece of public art in a place that was very much in need of it. Now, they just needed to find the right artist.

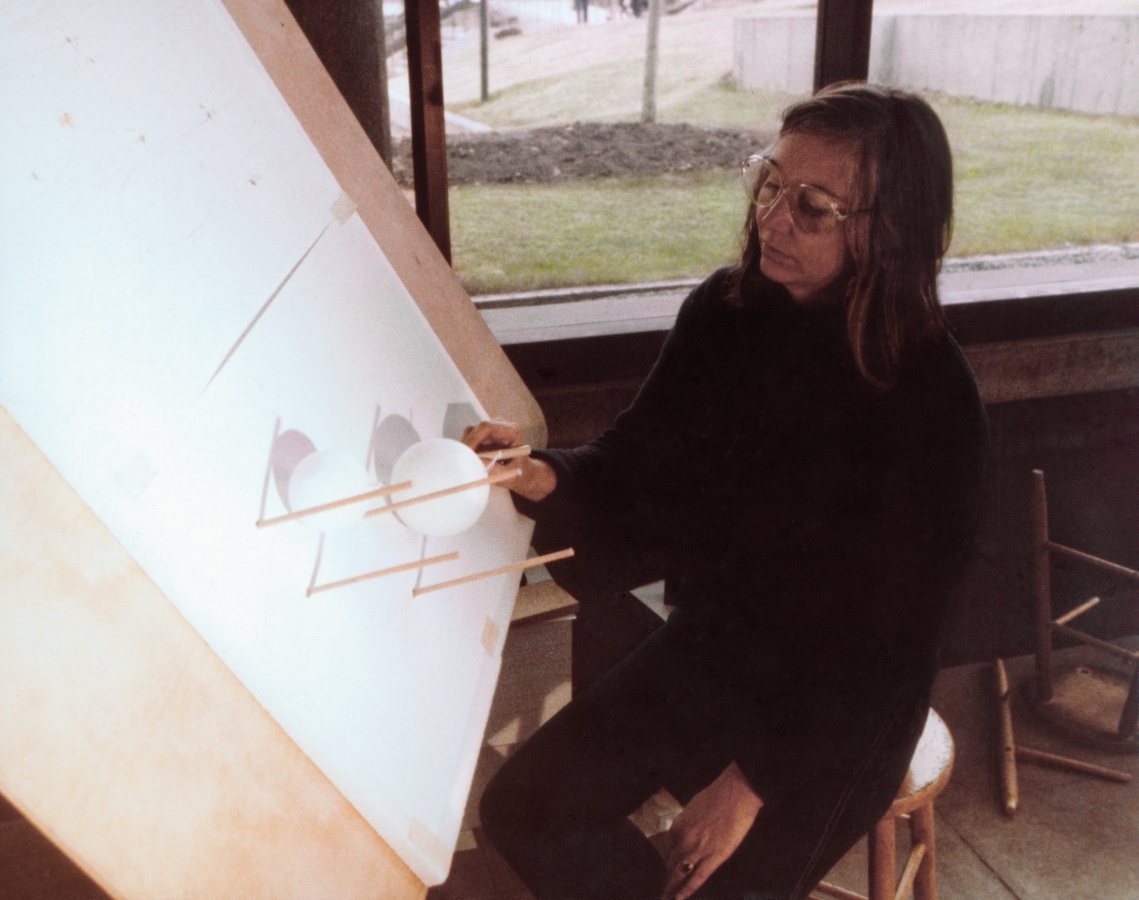

Nancy Holt, born 1938, grew up in New Jersey and began her career as a photographer. At 25, she married fellow artist Robert Smithson, who soon became known for his own environmental earthworks, particularly Spiral Jetty in Utah. In 1973, while scouting a new project, Smithson died in a plane crash in Amarillo, Texas. Soon after the loss of her husband, Holt began work on the project that first brought her mainstream attention, Sun Tunnels in Utah’s Great Basin Desert.

In 1979, Arlington recruited Holt for her ability to adapt large-scale art to the surrounding environment. While the county was certainly smitten by the artist, Holt wasn’t as effusive about Rosslyn. “I was overwhelmed with how cold and distant a place Rosslyn was,” Holt explained in 1988 documentary about the building of Dark Star Park. “It’s a concrete network here with very little thought about human beings, human scale, human maneuverability.” Additionally, the site the county was giving her was essentially a rundown, vacant lot. “This site was a trash site, had been a gas station and turned into a blight. It was all broken asphalt and weeds,” Holt remarked in the documentary. Nonetheless, she saw the potential.

“Because it was so decaying, Nancy was attracted to the possibility of turning it on its head,” says Le Feuvre. “She was always inspired by a challenge. It also was the ability to add something to a place where millions of people would see this work because they are traveling through.”

Holt also was confident enough to ask for something nearly unprecedented. At a time when artists of public projects were often not granted much autonomy, she was given complete control of developing, designing, and building the entire park. “She was quite smart in asking for it,” says Adams, who worked with Holt on renovations of the park. “She knew the opportunity wasn’t simply providing a work of art, but building a public park.”

Her vision included a great deal of very deliberate symbolism. The two spheres and steel rods located across the intersection in between North Lynn Street and Fort Myer Drive were designed so that only on each August 1 at 9:32 a.m., the shadows cast by the spheres would line up directly with the metal shapes on the ground. She chose August 1 because it’s the date in 1860 when William Ross acquired the land that became Rosslyn. As for why 9:32 a.m., Holt simply liked the shadows at that particular time.

Her aim in creating the alignment, as she said in the documentary, was to “integrate the historical time of the place with the cyclical universal time.” As for the name “Dark Star Park,” it comes from the idea that these spheres resemble fallen, extinguished stars—not the Grateful Dead song “Dark Star” like some believe. (August 1, coincidentally, also happens to be Grateful Dead’s frontman Jerry Garcia’s birthday. Adams says every year there are those who show up in tie-dye shirts thinking this is a celebration for Garcia.)

Work on the park took about five years. Holt first made miniature clay models depicting everything, from the spheres to the grass to the building next door. In the documentary, Holt admits that there were a lot of elements of park building that she wasn’t familiar with—particularly what material to use for the spheres. She settled on gunite, a sprayed mix of concrete, sand, and water that’s most often used in swimming pool construction. As Holt is quoted as saying in the documentary, the intent was to make sure they lasted “for the ages.”

As an artist and park designer, Holt was detail-oriented, demanding, and exact. She hired an astrophysicist and worked with the Naval Observatory on a formula to make sure the alignment was perfect. She learned that the wobble of the Earth caused issues for her perfectly planned shadow show. Holt admits that while 9:32 a.m. is the time given for the alignment, it could actually vary by a minute or so due to this phenomenon. From the alignment to the tunnel’s height, Holt oversaw everything and pushed it to be flawless.

Dark Star Park was dedicated in June 1984 and immediately became the centerpiece for what is now Arlington’s public art program. The park went under renovations from 1997-2002. By then, the spheres had begun to discolor a bit and leach and there were “desire lines” made by people cutting through the park. Despite these not being part of the artist’s original plan, Holt didn’t want to fix it. “She liked the way the piece evolved,” says Adams. “She liked the idea of a marker that would allow [visitors] to come back time and time again to observe change.” In the end, the renovations included repairing water pumps, relayering sidewalks, redoing the shadow patterns, and cleaning.

Nancy Holt died in 2014 but her legacy lives on in Rosslyn. Although Sun Tunnels was her more famous work, Le Feuvre says that Dark Star Park was may have been the artist’s favorite. “She wanted the [park] to be right at the center of people’s memory of how she added something to the world,” says Le Feuvre. “It really fulfilled a dream of Nancy’s.” In fact, the park is actually slated to expand, with work commencing imminently.

Adams remembers working with Holt as a young curator during those renovations two decades ago. She quickly learned about the artist’s dedication to the work. “I didn’t know a whole lot about her personal life and I asked her about children,” Adams says. “She looked at me and said, ‘my sculptures are my children.’”

In recent years, Holt has become more and more credited as being way ahead of her time. Last year, the famed Dia Foundation acquired Sun Tunnels and held an installation dedicated to her work and legacy. “She was one of the pioneers and, certainly as a woman, she was very unique in the field,” says Adams. “She helped change the conversation about public art.”

And one of her greatest works is in Rosslyn, nestled between a 1970s-looking building and morning rush hour. Perhaps that was Holt’s intention, to get rushing commuters to stop for just a moment and see that what’s in the sky can also be found here on Earth.

Matt Blitz

Matt Blitz