DCist is providing special coverage to climate issues this week as part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of 250 news outlets designed to strengthen coverage of the climate story. Many of these stories originated as questions from our readers.

When Brianne Eby goes to work, she bikes.

But as she cycles through the District, Eby isn’t just worried about getting to work on time, but how she’ll get around the city as the impacts of climate change become more apparent.

“I’m a bike commuter, so this is near and dear to my heart,” she says. “You need to have a variety of options. If I can’t bike, I have to rely on public transit. This is about improving modes of operation.”

Eby, who works in transportation policy, wants to know what will happen if heat, rain, or other weather events prevent her from cycling. Will she be able to rely on public transit? How is WMATA, Amtrak, Virginia Railway Express, the D.C. Department of Transportation, and the D.C. government more broadly preparing for how climate change could affect how we get around?

Two of the biggest concerns for transit are flooding and heat, says Harriet Tregoning, the former director of the District of Columbia Office of Planning and current director of the New Urban Mobility alliance at the World Resources Institute.

Soaring temperatures can impact the stability of rails, she says, and other extreme weather can impact people’s travel patterns. “Have you ever had to hail a ride because it was raining?” she asks. All of these changes might interrupt transportation services, she says, and not just for commuters.

In extreme heat, construction workers might be unable to work through the night for much-needed repairs to Metro, roads, and more. (The flipside, however, is that in mild winters, construction can be expanded. “Then, it becomes July,” she says, “and you can’t do as much work.”)

The effects of heat and flooding aren’t future concerns—they’re already affecting commutes.

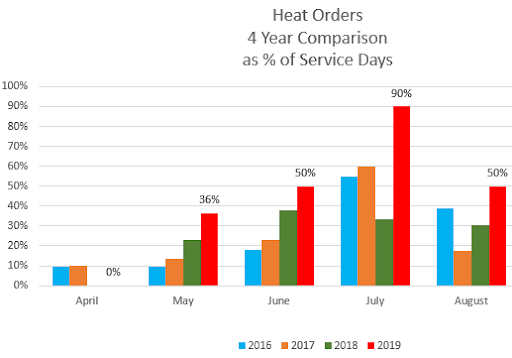

Over the past four years, the VRE has seen a steady increase in heat orders—namely speed restrictions that require trains to run 20 miles per hour slower, according to chief of staff Joe Swartz. Amtrak and Metro also have a similar policy, where the heat of the rails are measured and train speeds are adjusted accordingly.

The reason: heat can cause rails to buckle, which leads to concerns of derailments. Slower speeds, Swartz said, helps engineers visually spot a heat kink and stop the train in time.

For VRE riders, that means that trains reaching their final destinations about 8-10 minutes later than expected.

Heat orders are typically issued over a roughly 108-day period between April and September. Between 2016 and 2018, roughly 27 days a year required heat orders. That nearly doubled in 2019, with 49 such days. In July, they were necessary during 90 percent of the month.

“If that continues and continues to make us less reliable, people may think twice about taking us and the last thing we want is people choosing to drive instead of using our service,” he says.

VRE carries upwards of 20,000 riders a day, many of whom are “people who would normally be driving long distances off the roads,” he said.

Metro’s 2018 Sustainability Report mainly focuses on getting WMATA to reduce its energy use by 2025 and getting fewer people to drive and more people riding Metro.

“Choosing Metro is one of the easiest and most effective ways you can combat climate change,” a WMATA spokesperson said over email. “Each passenger that chooses Metrorail produces 40 percent less emissions compared to driving the same trip in a car.” (The transit agency has also been advertising these facts in signage around the system.)

The report includes some extreme weather measures, such as securing vent shafts and improving drainage in tunnels. And WMATA’s 2025 Energy Action Plan also features a number of initiatives, like installing LED lighting into all stations, speeding up the replacement of station chillers with cleaner technology, developing an electric bus strategy, among others.

Between 2019 and 2025, it aims to save 160,000 metric tons of CO2 emissions, which is equivalent to taking 35,000 cars off the road a year.

City officials also need to be concerned about emergency events, says Tregoning, pointing to what happened after the 2011 earthquake, when people left work in droves, causing gridlock in the streets. “How do you get people out quickly?” she asks.

D.C.’s first resilience officer, Kevin Bush, has been working on how to address D.C.’s “shocks” and “stresses” in his mission to make the city resilient against climate change.

A shock is a catastrophic event, he says, like a hurricane or a heat wave—or even a federal government shutdown. “The only way to really prepare with those shocks is to deal with our everyday stresses,” he says. And that includes improving means of transportation.

According to the interagency Sustainability DC 2.0 plan, the D.C. government is pushing for more commuters to consider options other than a personal car, including by expanding the D.C. Streetcar and improving biking infrastructure.

D.C.’s long-term plan is to expand the current bike lane network to include 44 miles of protected lanes and prioritize bike lanes east of the Anacostia River. It also aims to increase the number of Capital Bikeshare stations from 278 to 325 by 2020.

And polarizing feelings about scooters aside, Bush said increasing access to electric scooters in the city is not just about reducing carbon pollution (which, as DCist previously reported, isn’t always the case), but also giving people more transportation options.

“There’s a heat wave or flood or the Metro is closed, you have more options now at your fingertips to get where you need to go,” Bush says.

With more flooding in the future, it’s worth looking at what happened when record-breaking flooding coincided with morning rush hour in August: high-water rescues on the roads, power outages, and delayed transit services.

Climate change can cause frequent intense storms, which can overwhelm the capacity of storm sewers, Bush says.

It’s very possible that we’ll see more examples of water pouring into a Metro station, down the escalators, or even into your train. WMATA didn’t respond to direct questions about how the Metro intends to respond to extreme weather, except to say that it’s working on “several projects that directly relate to climate adaption,” a spokesperson said. This includes raising vent shafts, sealing tunnels, and upgrading pumping stations.

Bush notes that Mayor Muriel Bowser has invested $5.7 million over five years to fund a digital flood model of the District to predict catastrophic flooding that might impact the Metro or roads. “The mayor’s investment of better understanding our flood risk will identify the areas that are more at risk of flooding,” he says.

As for buses, WMATA’s energy plan says the city is investing in all-door boarding, and cashless and mobile payment methods to streamline usage. Additionally, we might see an electric bus pilot before 2025.

Bush said, however, it’s important that all of these solutions don’t just focus on managing the shocks of extreme weather, but the underlying issues of aging infrastructure, inequality, and population growth.

He gave the example of Hurricane Katrina: “It wasn’t just a disaster because it was a hurricane, but because of decades of neglect and rising inequality,” Bush says. “Climate is a threat multiplier.”

This story has been updated with a more accurate figure for Mayor Bowser’s investment in a digital flood model, and to explain that frequent intense storms overwhelm the capacity of storm sewers.