Haymarket, Va., population 1,900, looks like a typical small town with a main street lined with American flags and local businesses. There’s a town hall, white clapboard houses, a family dentist, and a small museum that was once a one-room schoolhouse. A few miles outside of the town’s center, it turns more suburban. There are shopping centers, fast food restaurants, housing developments, a country club, a golf course, a boy scout camp, a winery, and single family homes sitting on large tracts of land. Five miles down the road is where the first major battle of the Civil War took place. Washington, D.C., is only 35 miles east, though the two cities can feel like they’re a world apart.

And if things had gone slightly differently 25 years ago this month, this small Virginia town would have been the site of a Disney theme park.

On September 28th, 1994, the Walt Disney Company shocked the world by abruptly pulling out from building the $600 million, 3,000 acre Disney’s America, a proposed history-themed park, in Haymarket.

“Despite our confidence that we would eventually win the necessary approvals, it has become clear that we could not say when the park would be able to open, or even when we could break ground,” wrote Peter Rummel, president of Disney Design and Development Co., at the time.

Two and a half decades later, Disney’s America remains a fascinating and massive what-if for our region. How would have the economy changed? How it would have impacted transportation infrastructure? How would have Disney portrayed the complex, nuanced, not-always-happy story of America? Would the theme park really have destroyed historic battlefields? What lessons can we learn from this cautionary tale, particularly with the next billion-dollar company moving into the region?

“I still think about it,” says Debbie Jones, who was the president & CEO of the Prince William County-greater Manassas Chamber of Commerce (a role she remains in today). “Twenty five years later, would I still be so enthusiastic? Was it a missed opportunity? Or did we luck out that Disney didn’t come here? You know, I’m not sure.”

Disney’s America was years in the making and serious development had begun at least as early as 1991. For its third U.S. park, the company wanted a place that already had an established local and tourist base. According to an August 1994 feasibility assessment put together by Disney and obtained by DCist, the company targeted D.C. due to its 19.5 million annual tourists, which put it just behind Las Vegas as the fourth-most visited city in the country. It also notes that, at the time, the “Washington D.C. regional/theme park market is significantly underserved.” Disney did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

While they considered D.C. proper and closer-in suburbs, Disney ended up a bit further out at Haymarket because of the availability of land. And they obtained the land secretly, using many of the same methods the company used in Florida a few decades earlier: shell corporations, purchasing options, and hidden identities.

According to the Washington Post, Disney employed 34-year-old “Scott Roberts” to go to Northern Virginia to scout and negotiate. To local real estate brokers, Roberts was from Phoenix, Ariz., and was there representing a “confidential trust.” To be convincing, he studied up on the city’s NBA team and pretended to board flights bound for Arizona. Only days before the announcement, Roberts—who was actually named Scott Stahley—revealed his true identity to those he had been working with by opening a briefcase full of Disney dollars at dinner at a Morton’s Steakhouse in Tysons.

The reasoning for all of the secrecy, according to the Post, was that if it got out Disney was buying land for a new theme park, prices would skyrocket.

“Disney… wanted enough land not only for its current vision, but its future vision as well,” Dana Nottingham, Disney’s America’s director of development and, later, president of the project, tells DCist, acknowledging that the land acquisition was conducted in secret.

In total, Disney ended up purchasing or optioning 3,000 acres of land in Prince William County (2,000 of which was owned by Exxon) just off I-66.

The company only started telling local officials about what they were up to after acquiring the land and mere days before the announcement. George Allen, who had just been elected Virginia’s governor, remembers he was first told about it a week before. Quite ironically, he was on vacation with his family at Disney World when he got the call. “We just had pictures taken with Mickey Mouse … and [I] was told that [then-Disney CEO] Michael Eisner wanted to talk to me,” Allen tells DCist. “I called him back on a pay phone between AdventureLand and Frontierland. That’s when I first heard about the whole project.”

Haymarket’s mayor at the time, Jack Kapp, was told about Disney’s plans 24 hours before the announcement. “They laid out everything they were going to do and asked us to not tell anybody,” Kapp says of Disney executives’ visit to his house. “Then, Thursday, the next day, they made their announcement.”

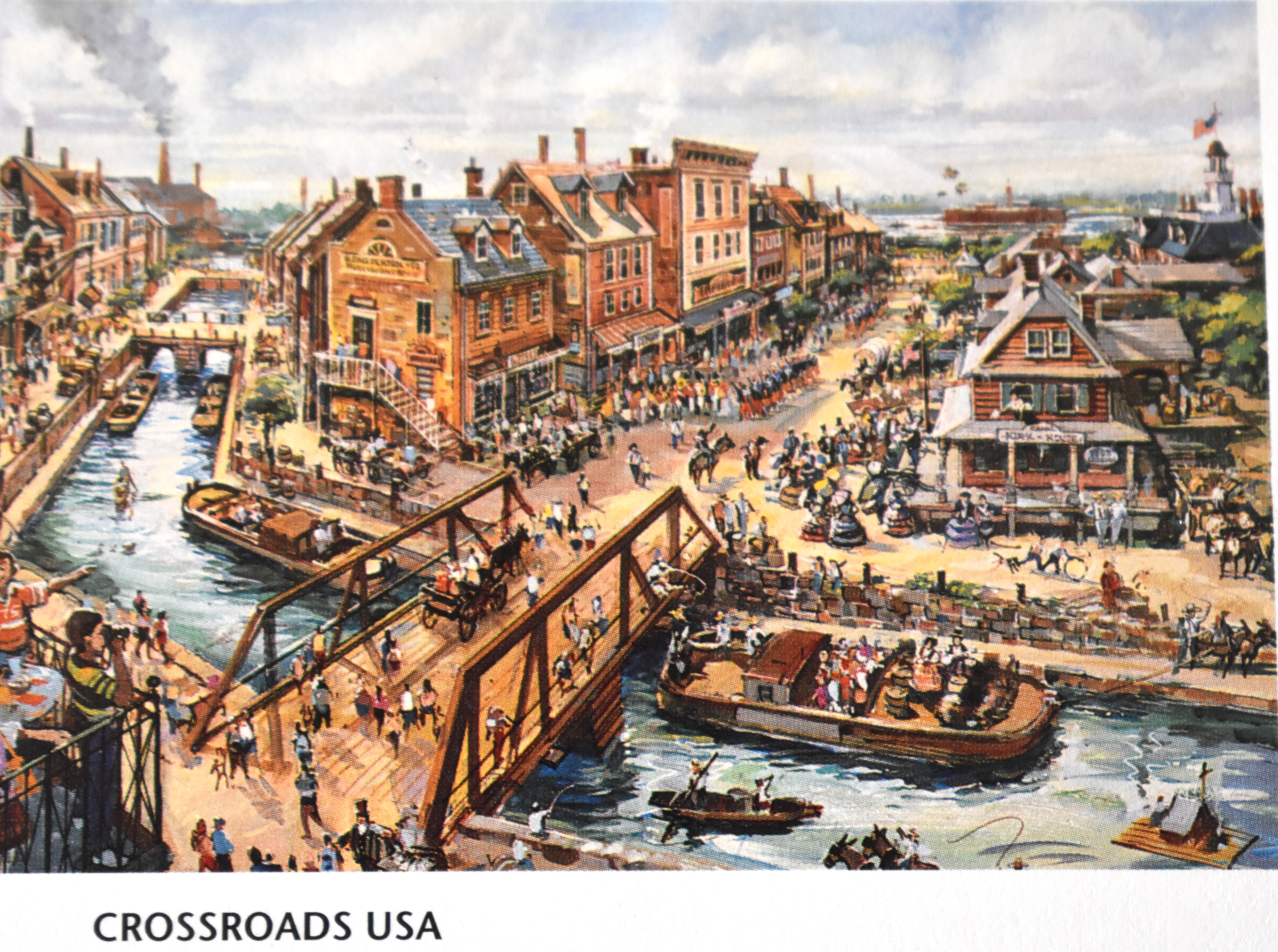

In front of a packed house in nearby Manassas, Disney CEO Michael Eisner and the rest of his team laid out their ambitious plans. Set to open in 1998, Disney’s America was to have nine sections loosely based on important periods of American history. There would be a colonial President’s Square, a Native American village, a recreation of Ellis Island, an industrial revolution factory town, a Civil War fort, a small-town USA county fair, an early 19th-century port of commerce, World War II-inspired Victory Field, and a Great Depression-era family farm. Attractions would include a roller coaster ride through a turn-of-the-century steel mill, a virtual reality-aided parachute jump from a World War II fighter jet, and a 3-D immigration-themed movie inside of the Statue of Liberty hosted by the Muppets. At night, in lieu of fireworks, there was to be a nighttime show recreating the Civil War naval battle between the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia.

The park would celebrate “the nation’s richness of diversity, spirit and innovation” and be “an ideal complement to visiting Washington’s museums, monuments and national treasures.”

There was also eventually going to be hotels, retail options, a golf course, and a studio where they could televise political and historical debates. There was even talk of Disney-led bus tours to the Washington Monument and Smithsonian museums, and to the Gettysburg and Manassass battlefields.

The company known for fairy tale endings said it wouldn’t shy away from the more controversial aspects of American history either. As Bob Weis, a Disney senior vice president at the time (today, president of Walt Disney Imagineering) said, “This is not a Pollyanna view of America” and promised “painful, disturbing and agonizing” exhibits on the Vietnam War, Native Americans, and slavery.

From a business point of view, it was advertised as a huge economic and development boon for the region. Though plans were for the site to be about one tenth that of Orlando’s campus, and attendance estimated to be at only about 6 million visitors per year, Disney’s America also came with the promise of thousands of new jobs, millions in revenue, a reinvestment in transportation infrastructure, and increased financial resources going back to schools.

For these reasons, many at the local level were excited for the project. “It let the world know that Virginia was open for business. Tourism is such a clean industry,” says Allen. “It would have been great for Virginia in so many ways.”

Jones, as CEO of the local chamber of commerce, took her cues from her members. She said nearly 40 different business organizations were present at the press conference to show their excitement. “[Disney] was very, very specific about using only chamber members as vendors,” she says. “So, providing those unique opportunities for our members was great.” Kapp was also in support, but for a much simpler reason. “I’d thought it would be good family entertainment.”

It was during this introductory press conference that Disney’s Bob Weis made a comment that, in many ways, set the wheels in motion for Disney’s America downfall a mere ten and a half months later. “We want to make you a Civil War soldier,” said Weis of visitors to the park. “We want to make you feel what it was like to be a slave or what it was like to escape through the Underground Railroad.”

The backlash was swift. Days after the announcement, Washington Postcolumnist Courtland Milloy criticized the Mouse for using slavery as captalistic entertainment. “In a nation that buys wholesale into Rush Limbaugh and Howard Stern,” wrote Milloy, “who can blame Disney for figuring that some of these same customers would be amused by black people strapped to a whipping post in 3-D Sensurround sound?”

Historians across the spectrum took umbrage with not only Weis’ comment, but the perceived “Disneyfication” of history. David McCullough, author and narrator for Ken Burns’ seminal documentary series The Civil War, said at the time, “We have so little left that is authentic, that is real, and to replace it with plastic history, mechanized history, is a sacrilege.”

The criticism wasn’t solely tied to Disney’s approach to American history, either. In the spring of 1994, about 30 historians and writers formed the group Protect Historic America specifically in response to the planned park’s location, only several miles down the road from the Manassas Battlefields. “We anticipated that the development and traffic associated with the opening of the park….would have severely impaired people’s ability to come visit, understand, and appreciate the battlefields,” says the group’s president James McPherson, a Civil War historian, professor, and author.

Today, McPherson says that, theoretically, he has no qualms with Disney’s attempt to create an American history park. “Some may be better than others, but you don’t need a license to practice history,” says McPherson. “Disney had its own perspective and has done good work in other contexts in getting people interested in history. We were laser focused on the actual threat to the battlefields.”

There were also environmental concerns, led by the Piedmont Environmental Council that development would lead to increased pollution and the destruction of natural resources.

Additionally, there were accusations that land-owning gentry in nearby Fauquier County, or as some called them, the “foxhunters,” were bankrolling these opposition groups in an effort to keep land undeveloped.

As expected, Disney came out firing. They company announced that it had hired its own historians, James Oliver Horton and Eric Foner, to help consult with them on the authenticity and potentially sensitive nature of the park. When reached for comment, Foner said via email, “I may have been listed as an advisor but have no recollection of having given any advice or playing any role at all.”

In a December 1993 interview, Michael Eisner attempted to minimize Weis’ comments by saying the company’s vice president wasn’t “a person who generally talks to the media” and the criticism about how Disney would portray slavery was a premature assumption, “which is always dangerous.” He said that the overall message of the park should be that America “is the best of all possible places, this is the best of all possible systems.” In the same interview, he also threatened to pull the project if “special-interest groups” continued their attempt to destroy it and the Virginia General Assembly didn’t approve the taxpayer-funded transportation improvements that Disney wanted.

It was around this time when Hampton, Va.-native Dana Nottingham got involved. He had been director of retail development at Disney World before getting the call to move back to his home state. He became director of development for Disney’s America and pretty much the spokesman for the project. “My role evolved into a… far more public [one] than I could have imagined,” Nottingham tells DCist today from his Atlanta home. He says was involved in everything: decision-making, talking to the media, and deciding the creative direction of the park.

Nottingham says he trusted his employer as a storyteller and believed that Disney was very well-equipped to deal with the complexities of teaching American history. As a parent of two daughters, he commends Disney for their forward-thinking approach. “I’m an African American parent. I’m black,” Nottingham tells DCist, “There was no African American museum at the time. That did not exist. You can bash Disney all you want, but it’s pretty bold to even try to take on that.”

While the Virginia General Assembly fairly quickly approved the needed $163 million taxpayer-funded transportation package that focused on improvements to I-66, Disney’s problems didn’t go away.

In June 1994, about eight months after the announcement of Disney’s America, 16 U.S. House of Representatives members took up the cause of park opponents and persuaded the Senate Natural Energy & Natural Resources subcommittee to hold a hearing. Texas Democrat Michael A. Andrews told the New York Times that this was “far more than a local issue” due to the potential impact on historic sites, the environment, transportation infrastructure, and smog (a problem we still have today). The entire 4-hour hearing aired on C-SPAN and featured many of the significant players being questioned by U.S. senators. It featured debates about traffic, Holiday Inns, sewer run-off, and Senator Ben “Nighthorse” Campbell brandishing Mickey Mouse ears.

George Allen spoke at the hearing but resented the federal government getting involved because he believed this was a state and county issue. “I was aggravated that I had to waste time arguing with senators on something that’s none of their stinking business,” says Allen today.

In the end, the hearing didn’t amount to the federal government taking any action, but it did get Eisner to once again make comments that painted him and Disney as out of touch. Eisner said that, upon making the announcement, he had “expected to be taken around on people’s shoulders” for spending $650 million on a theme park in rural Virginia. What’s more, he thought Disney was doing a favor for the historians who opposed the project. “I sat through many history classes where I read some of their stuff, and I didn’t learn anything,” said Eisner, “It was pretty boring.”

The backlash intensified. In September 1994, nearly 3,000 protesters (including Ralph Nader) marched on D.C. where they chanted, “Hey, hey, ho, ho, Disney’s got to go.’”

There was very little indication from the Walt Disney Company that September 28, 1994, was going to be the day that everything changed. Jones, then-chamber of commerce president, says she was at a meeting the night before with a Disney management team member, who gave no indication anything was up. Allen says he was preparing for his weekly radio appearance, excited to talk about other things besides Disney. Jack Kapp, Haymarket’s mayor, says he thought the park was a sure thing right up to the moment it wasn’t.

That evening, Disney made its decision public: The company would be pulling out of the Haymarket site. “We remain convinced that a park that celebrates America and an exploration of our heritage is a great idea, and we will continue to work to make it a reality,” wrote Peter Rummel, president of Disney Design and Development Company, in a statement. “However, we recognize that there are those who have been concerned about the possible impact of our park on historic sites in this unique area, and we have always tried to be sensitive to the issue.”

”[We] had what I would compare to a wake after the announcement,” says Jones. “I ran into that same guy [from the meeting] and I said, ‘Okay, either you’re the best actor in the world or you had no clue.’ He looked at me and said ‘I had no clue.’”

“My sister called me up from California and said ‘Jack, I’m so glad that Disney isn’t going to be building on the Manassas Battlefield,’” Kapp recalls. “That was the propaganda that the anti-Disney people was putting out there. But it wasn’t going to be built on the battlefields.”

Allen went on radio the next morning in a somber mood. “I opened [my appearance] with saying ‘It’s still a beautiful day and Virginia’s still a great state.’ I had to cheer myself up on live radio.”

In the end, Disney surrendered due to overwhelming public backlash, and potentially, factors outside the scope of the project; like Eisner’s open heart surgery, Disney’s President Frank Wells tragic April 1994 death, and the financial difficulties of Euro Disney. In keeping with the Civil War theme, Disney was fighting battles on multiple fronts.

For a short time afterwards, Disney attempted to find another site for its American history theme park. But, eventually, those plans dissipated. Disney tried once again to come to the D.C. area in 2011 with a resort hotel at National Harbor, but that too was cancelled.

Disney’s America leader Nottingham says the project’s failure had a lot to do with trust and leadership. He firmly believes to this day that Disney would have told the story of America in a “manner that was accurate, relevant, and sensitive” and would have evolved with the times. But the public didn’t trust them.

“I understand why people couldn’t [give Disney the benefit of the doubt] because of the way things were handled,” says Nottingham. After the company pulled out from Haymarket, he was promoted to the role of president of Disney’s America, tasked with heading up an (ultimately unsuccessful) attempt to find a new location for the park. He cites the land acquisition strategy, perception, and less-than-tactful media appearances as reasons for eroding trust.

“Optics can make some people question how you operate,” he says. “You have to have leaders that get it and navigate those nuances. The biggest lesson is that the culture of the place is just as important as real estate fundamentals.”

Over the last 25 years, development has come slow and steady to Haymarket. Toll Brothers has about 2,200 homes on and near the property that once was going to house Disney’s America. A $17 million boy scout camp also sits on the property. Jones says that the project had a long-lasting positive effect, attracting other businesses and eventually leading to the building of what’s now called Jiffy Lube Live. Allen still thinks Virginia would have been much better off in terms of tax revenue and jobs if Disney had come.

In some ways, Disney nearly coming to Northern Virginia is comparable to Amazon’s arrival to Arlington and Alexandria: It’s another big, billion-dollar media company bringing with it the prospect of jobs, tax revenue, and development, but also facing public scrutiny.

“[Amazon] should call me up,” Nottingham says with a chuckle.” I would tell them that overconfidence can dull your blade in combat.”

Matt Blitz

Matt Blitz