For many white-collar office jockeys in the District, WeWork has been a blessing.

The coworking provider put stylish, transit-adjacent workspaces within reach for people who can’t afford corporate suites. It gave lonely telecommuters a place to work outside their homes. It normalized free coffee and foosball in the workplace. And it raised the bar for other employers, who have raced to upgrade their digs after WeWork made their offices look depressing by comparison.

But WeWork itself is running out of blessings—and the company’s enormous financial problems could send ripples across the D.C. region.

That’s because WeWork is the largest single private occupant of office space in the District. The company went on a D.C. leasing spree in the months before its anticipated initial public offering and now leases more than 1 million square feet across 15 buildings in D.C. (The company is part owner of a 16th property in Dupont Circle, and it also holds leases at several buildings in Virginia and Maryland.)

That IPO was canned after investors took a peek at the company’s financials and didn’t like what they saw. In short, WeWork spent too much and earned too little. Now, all those leases could be on shaky ground, as the company has announced layoffs and other cost-slashing measures.

A WeWork spokesperson declined to say whether the company plans to downsize or lay off employees in the D.C. region, but said the company “expects to grow our core business here” and open new spaces in the year ahead.

What could WeWork’s challenges mean for the future of coworking in the D.C. area? We posed that question to a few close observers of commercial real estate in Washington. Here’s what they said.

If WeWork Goes Under, D.C. Office Space Could Get (Slightly) Cheaper

Historically, WeWork has liked to lease, not own, which means its problems could become its landlords’ problems.

WeWork isn’t expected to go bankrupt at this point. But if it did, its leases would become worthless, and more than 1 million of square feet of commercial space would be thrust back onto the market. That’s bad news for D.C. landlords who are already struggling to fill their buildings, says Gerry Widdicombe with the Downtown D.C. Business Improvement District.

“The downtown office market, I guess, could optimistically be described as going sideways,” Widdicombe says.

Downtown D.C. had a record-high vacancy rate of 12.6 percent in 2018, according to the BID’s latest State of Downtown report, largely due to a jump in competition and employers cutting back on the amount of space they lease. Many landlords are working hard to attract tenants, Widdicombe says, by offering free rent and other perks. If even more space opens up, pressure to offer concessions will only increase.

Then again, says Jon Glass with real estate advisory firm Savills, that’s a good thing for anyone looking to rent office space.

“More vacancy provides [tenants] with greater leverage and ultimately better economic leasing terms,” Glass says.

WeWork’s Competitors Could Get A Boost

WeWork is the biggest name in coworking, but it has plenty of competition from companies like Cove, MakeOffices, Mindspace, HeraHub, and The Wing. If WeWork begins to cut back on the amenities it’s become known for — like concierges and free drinks—members might jump ship to a cheaper competitor, says Willy Walker, chairman and CEO of commercial real estate finance company Walker & Dunlop.

“The reason people went to WeWork was A) they had the brand and B) they had the amenities and services that nobody else had,” Walker says. “[But] where they used to differentiate on exceptional service, they’re not putting the money into the exceptional service anymore.”

In other words, if workers have a choice between a $900 WeWork office with no concierge and another company’s $600 office with no concierge, people will probably choose the latter. And long term, that’s not good for WeWork, because they’ll have to start lowering their prices, Walker says.

“It means they’re in a death spiral as it relates to the rents they can charge,” the CEO says.

But a WeWork death spiral would present an opportunity for WeWork’s rivals—which include at least one of its landlords. Carr Properties, which has deals with WeWork in multiple buildings in D.C. and Maryland, also has its own coworking brand. If WeWork moves out, a company like Carr would be well-positioned to take its place. (Carr didn’t return WAMU’s request for comment.)

“They could potentially go in, rebrand it, and just take over the space,” says Harry Dematatis with commercial real estate services provider KLNB. “It’s already built out as coworking. [The landlords] could run it themselves.”

Coworking Will Remain Popular … Unless The Economy Tanks

The rise of WeWork made it clear that people really like shared offices, says Jon Glass with Savills—and that demand doesn’t appear to be going anywhere.

“What WeWork did was really illuminate demand for coworking among the changing workforce,” Glass says. “They realized that tenants were willing to pay a premium for lease term flexibility, and tenants wanted to avoid the cost risk and resources devoted to building out new space.”

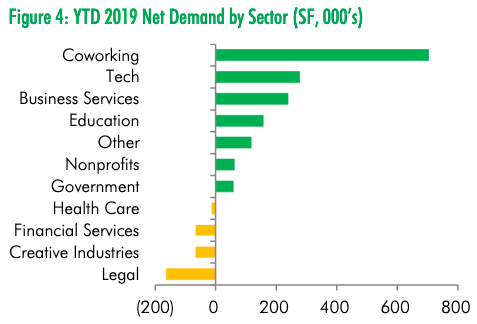

That’s why coworking continues to drive most new leasing activity in D.C., according to CBRE.

But that could easily change if the economy takes a downturn—which is possible, with some analysts saying there’s a 26 percent chance of a recession in the next 12 months.

That has big implications for coworking, says Walker & Dunlop CEO Willy Walker.

“The whole shared workspace thing is really dependent on a very steady economy. And the moment you have any movements in that, that’s the first thing that goes,” Walker says. “People just say, ‘You know what? I’m not going to pay for the WeWork space anymore. I’m going to go and meet with my buddies at Starbucks.’”

This story originally appeared on WAMU.

Ally Schweitzer

Ally Schweitzer