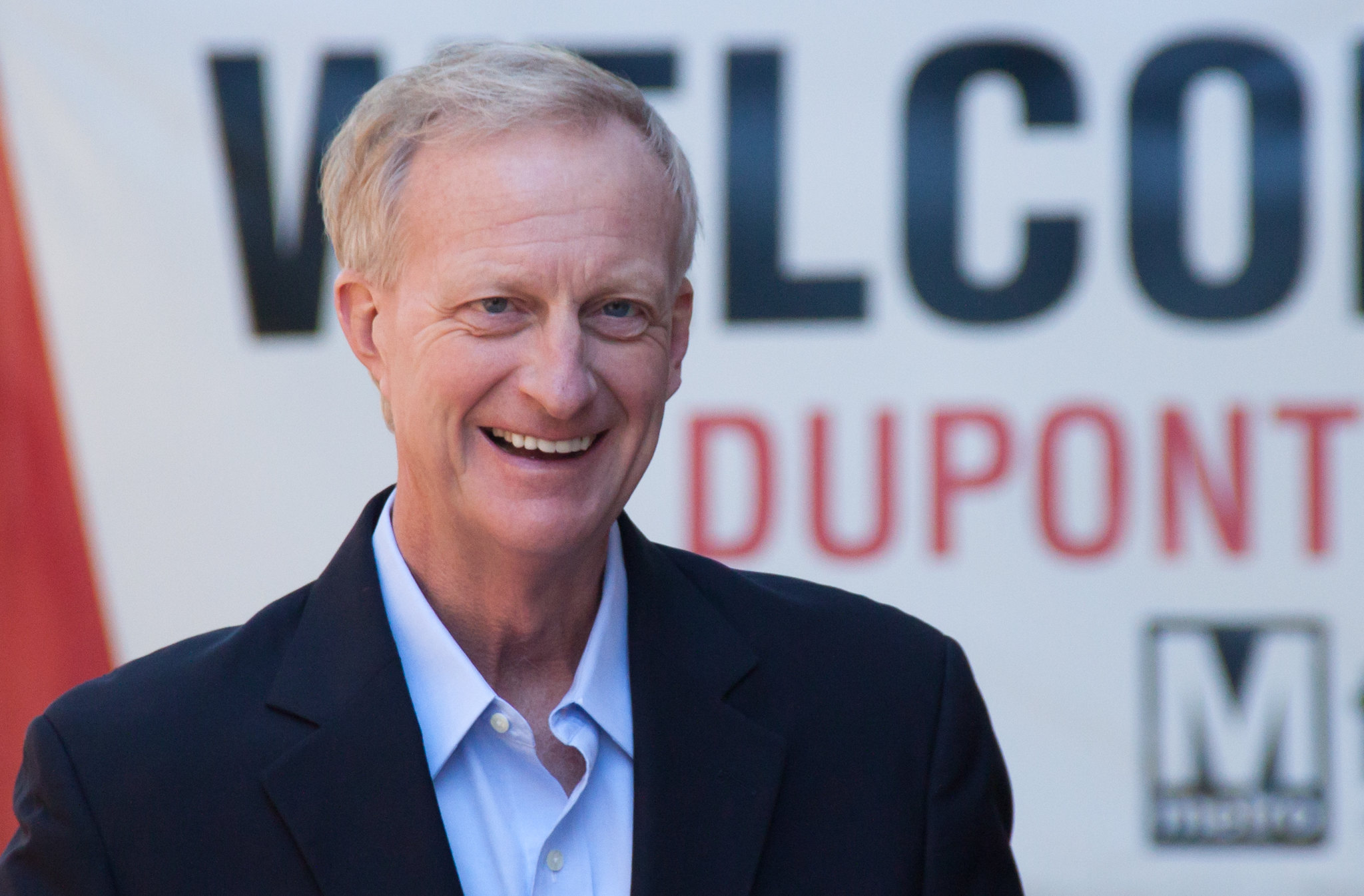

Any reporter, activist, or elected official in the Wilson Building knew the drill: once Ward 2 Councilmember Jack Evans got to talking, it was only a matter of time before he mentioned how long he had been in office.

He often delivered the information as a historic credential of sorts, a way to inform everyone around him that they should probably listen to him, since he had been there and done that. Sometimes his colleagues rolled their eyes, but they also often deferred to Evans’ deep well of local knowledge and experience.

But as of the close of business on Friday, that all comes to an end. After 28 years, eight months, and five days on the D.C. Council, Evans is resigning from office, leaving the institution where he served longer than anyone in the body’s history. He departs willingly, somewhat: his colleagues were expected to expel him later this month, a coda to a mounting scandal prompted by the businesses and developers who paid him to serve as their eyes and ears on the ground—and sometimes more than that.

Evans isn’t the first Council member to resign or leave in disgrace—there was Kwame Brown and Harry Thomas, Jr.—but he may be the one whose impact has most broadly been felt in the city. And it’s prompting a flood of competing reactions: some of his closest allies worry of the loss of institutional knowledge and business-friendly legislating, while critics see it as an opening to change the way D.C. approaches its growth and development—especially in the era of gentrification and displacement.

From Near Bankruptcy To Boomtown

Barbara Lang finds herself in the former camp. She was the president of the D.C. Chamber of Commerce from 2002 to 2013, and says he was a key voice on the Council, especially around the mid-1990s, when the city’s finances tanked and a federal control board took over.

“He was part of almost every economic development initiative that came forward for the city,” she says. “It was critically important.”

Evans refused to comment for this story, but in interviews with Council investigators last year he explained that his early years on the Council were focused on doing whatever he could to attract business and investment to the city, primarily downtown, which was part of his ward. Only with those businesses could D.C. right its finances, he told them.

“What is my political philosophy? So one was to rebuild downtown, because without money you can’t run anything. And when the city fails, the people who suffer the most are the people at the low end of the income scale, not the rich people. Because they can buy their way out,” he said.

Evans steered the massive projects credited with revitalizing Chinatown, the Wharf, and Shaw: the Capital One Arena, a new Convention Center, a renovated O Street Market in Shaw, Nationals Park, and more. (Evans kept ceremonial shovels from the many groundbreakings he attended in his first-floor office in the Wilson Building.) Imagine D.C. without those, he told investigators: “We’d be Detroit. And we’re not. So those were the building blocks that produced neighborhoods that have revitalized the city.”

As D.C. inched towards financial self-sufficiency, Lang says Evans—and his memory of the Control Board era—offered needed reminders to other lawmakers to court businesses and budget conservatively. “He would often remind his colleagues what it was like to not have control of the city’s destiny. That voice will be missed,” she says.

Lang worries that with Evans gone, businesses big and small will have one less vote on the Council willing to consistently side with them. She says it’s a trend she saw from when she started at the Chamber of Commerce in 2002 to when she left in 2013.

“When I took the job as CEO of the chamber I had five votes I knew I could count on and I had to work to get the other two to get to seven,” she says, referring to the number of Council members it takes to pass a bill. “When I left the chamber, I had maybe two I could count on and I had to work for five [votes].” She says she’s not sure even those two remain today.

Back to ‘Tax and Spend’ Days?

It’s a common complaint from D.C.’s business community: progressive lawmakers are making it more expensive to operate in the city with laws that do everything from increasing the minimum wage to mandating paid family leave. And without Evans around, some businesses worry it might get worse.

Speaking to Council investigators, Evans said as much. “We’re back in the tax and spend days from the 1980s and 1990s that bankrupted the city originally,” he said.

Chairman Phil Mendelson, who joined the Council in 1999, doesn’t think Evans’ departure alone will lead to more tax increases, but says the business community does have a reason to be worried about their influence inside the Wilson Building. “The business community should be concerned,” he says. “I believe in moderation, and we need to have the right balance.”

But some current Council members think that’s overstating the risk of Evans’ departure, including Ward 5 Councilmember Kenyan McDuffie, the current chair of the business and economic development committee. He also took over some of the duties Evans had handled as chair of the finance committee, before he was stripped of them last year amid the investigation into his ethical misconduct.

“No, I don’t think it will become a tax and spend frenzy,” says McDuffie. “We still have our 24 consecutive balanced budgets, we still have a triple-AAA bond rating, and I look forward to maintaining that growth, but doing so in a way that is more economically inclusive.”

And that’s a key issue for some of Evans’ longtime critics. They say that he had an almost single-minded focus on economic growth, without stopping to ask who benefits and who might be hurt—especially as development and consequent gentrification started picking up steam.

“I actually think we need fresh eyes to look at our current situation. One of Council member Evans’ challenges was that his mindset was still stuck in the mentality that D.C. is desperate for development and that we should do anything for development as opposed to we need to manage development to make sure it benefits D.C. residents and addresses our major challenges,” says Ed Lazere, director of the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute.

Corporate Tax Breaks Vs. Social Programs

Lazere also says that for all of Evans’ criticism of city spending on social programs, he was all too willing to shell out public dollars in the form of tax breaks and incentives to attract or keep big businesses—even when it wasn’t necessary. Last year, the Council voted to scale back incentives for tech companies that the city’s chief financial officer said were ineffective. Evans ultimately sided with the change to the law (which he had co-authored in 2000), resulting in $16 million in additional funding for homeless services and school-based mental healthcare programs.

But in late 2018 he also pushed through a $5.2 million property tax break for Chemonics, a for-profit international aid company, despite the fact that the CFO said there wasn’t enough information to show that Chemonics needed the break and that deals of this sort rarely influenced decisions about where companies locate.

“Jack’s eagerness to promote development often led to big corporate subsidy deals with often no strings attached even when the evidence suggested those subsidies weren’t needed,” he says. “I do think we can do better now. I think we should eliminate subsidies and loopholes that don’t actually work, and then we can use those resources for things that do, like supporting early childhood programs.”

Moving forward, business advocates say they will likely be turning to Mendelson, McDuffie, Ward 7 Councilmember Vincent Gray and Ward 4 Councilmember Brandon Todd for support, as well as Mayor Muriel Bowser. But some also say that they remain optimistic that the Council won’t suddenly lurch left upon Evans’ departure.

“I’m optimistic that there has been a growth in understanding on the Council in recent years about the very significant and critical contribution that the local business community plays in the health and well-being of the District,” says Mark Lee, coordinator of the D.C. Nightlife Council, which represents bars and restaurants.

‘I Think It’s Very Sad’

“There’s a stronger sensibility about the need to protect and preserve the very unique small business community that the District enjoys and that fuels the economy here, and also provides the resources for the policy initiatives and social benefits that we the city takes great pride in,” he says.

To that end, McDuffie and Ward 6 Councilmember Charles Allen have sponsored a raft of bills to help struggling local businesses. And in late 2018 the Council overwhelmingly voted to overturn Initiative 77, a voter-approved measure that would have increased the tipped minimum wage—a proposal strongly opposed by many bar and restaurant owners.

Mendelson says there will be a period of adjustment, especially once someone is chosen to replace Evans. A special election to finish out what’s left of his term, which ends in January 2021, is scheduled for June 16. The primary election happens two weeks before that; the winners of that contest will compete in November’s general election for a full term representing Ward 2 on the Council.

“On a personal level, I think it’s very sad,” says Mendelson, who worked alongside Evans for more than two decades. “Jack, for all his accomplishments, will be remembered for having had to resign. But from the standpoint of the institution, what we have done, which was to call for his resignation and indicate we would expel him if he didn’t, was the right thing to do.”

This story originally appeared on WAMU.

Martin Austermuhle

Martin Austermuhle