For 13 days — day after day, and night after night — demonstrators shared their grief, their anger, their fear, their demands, their joy, their hope for change, and so much more with our reporters.

These conversations have lingered with us for many days, and we expect that will be the case for a long time to come.

While we have worked to center protesters’ voices in our coverage, there’s so much that didn’t make it in — so many stories that still need to be told. So as we hit two weeks of sustained demonstrations, we asked our team to open up their reporter’s notebooks and share the sentiments that have stuck with them. Carmel Delshad, Jenny Gathright, Rachel Kurzius, Elliot Williams, Nathan Diller, Hannah Schuster, Matt Blitz, and Margaret Barthel contributed the quotes below. As the protests continue, we’ll keep listening. —Rachel Sadon

Rico Silva (DJ Quick Silva), of Prince George’s County, protesting at the base of the Lincoln Memorial on Saturday, June 6:

“When they say justice for all, it has to include black lives. And for years, black lives have not mattered. And right now we’re telling you we want to take out justice because you’re not giving it to us. We took a knee and you called us sons of bitches. We did everything peacefully and we never got any results. So right now we’re going to keep fighting and keep band loud until we get to the justice that we deserve in America.”

Kerry Payne, of Montross, Virginia, who drove just under two hours to protest in front of the White House on Sunday, June 7:

“It seems like as black people we keep struggling with the same issues over and over and nothing’s been done, nothing’s being changed. We must fight for our rights and fight for change. … [In Montross, there are] a lot of minorities, Hispanics and Blacks, but the white people, they control most of the power. And it’s hard to get ahead. We do have some allies there, and we’ve got some people that’s for us, but there are other people that’s against us as well.”

Aldrich, a 26-year-old who declined to give his last name in front of the White House on June 7:

“Reparations is what black people are owed: money, land, education, free health care. We’ve been owed that for a long time. We’ve had a 400-year contract that is up. We’ve been oppressed, impoverished, no housing. … Enough is enough. We built this country for free. We’re still getting shot. The law of the land doesn’t apply to us.

Last month, did we not watch white people storm a capitol in Michigan with assault rifles asking for a goddamn haircut? And what did [President Donald Trump] say? “Those good people.” Open it up, governor of Michigan. … But the very following month, when we’re getting sick and tired of black people getting killed and we protest, the commander in chief and leader of the free world called black people thugs. Do you see the foolishness? Do you see the tap-dancing around what they really want to say?”

Mike Whitfield, who recently moved to Los Angeles from D.C., speaking on June 4 after protesting at the White House:

“Staying at home, I would see the video of George Floyd or videos of the police beating protesters and things like that … and at a certain point, I realized, not only am I not out there protesting, I’m also not doing anything here at home. That’s what made it especially unbearable to watch that stuff.

After coming out to protests and starting a supply table to help people in case of tear gas, “I’ve barely paid attention to Twitter and Instagram, and I’ve been able to come home and feel like I actually might have made a difference or helped someone. That sort of takes a little bit of the sting away, until you remember that there’s so, so, so, so much more that I have left to do.”

Sandy Patel, of D.C., speaking on June 4 after protesting at the White House:

“Some of the larger protests I’ve been to, like the Women’s March … I didn’t see people going around, writing information or resources on their arms … or giving everyone a water bottle. Here there are people maneuvering through the crowds, checking on people, giving people snacks. So I do think COVID did bring about a new way to protest in a way more collective manner.”

Rasa, who declined to give their last name, speaking at the LGBTQ rally in Columbia Heights on Sunday, June 7:

“There’s nowhere else for me to be. There’s nothing else for me to do. Nothing else matters but fighting for people who have been oppressed long enough, never deserved it. And everything this country does have to be proud of, they owe to black people, they owe to the people that they subjected the most. And beyond wanting to highlight and support that cause, it’s therapeutic for me to be here, you know, to be here in solidarity with my people. This is the only way I can heal myself.”

Anisha Shetty, after being arrested on Swann Street:

“It was really traumatic for a lot of the activists, especially when they’re sitting there pleading for their humanity, or to be let go, or that they’re afraid and they’re not getting any response from cops. We’re not getting any information. It’s still light out when we were detained. It’s just so ridiculous that it’s for [a curfew violation] and that there’s so much military presence, and such an excessive use of resources for something that was so peaceful—and honestly, an expression of rights. And to do it in a residential neighborhood … like you literally had to trap and detain us? … It’s just kind of a waste. But I hope that in a way, it’s a bit of a wake-up call to D.C. and to the mayor and to the world that enough is enough.”

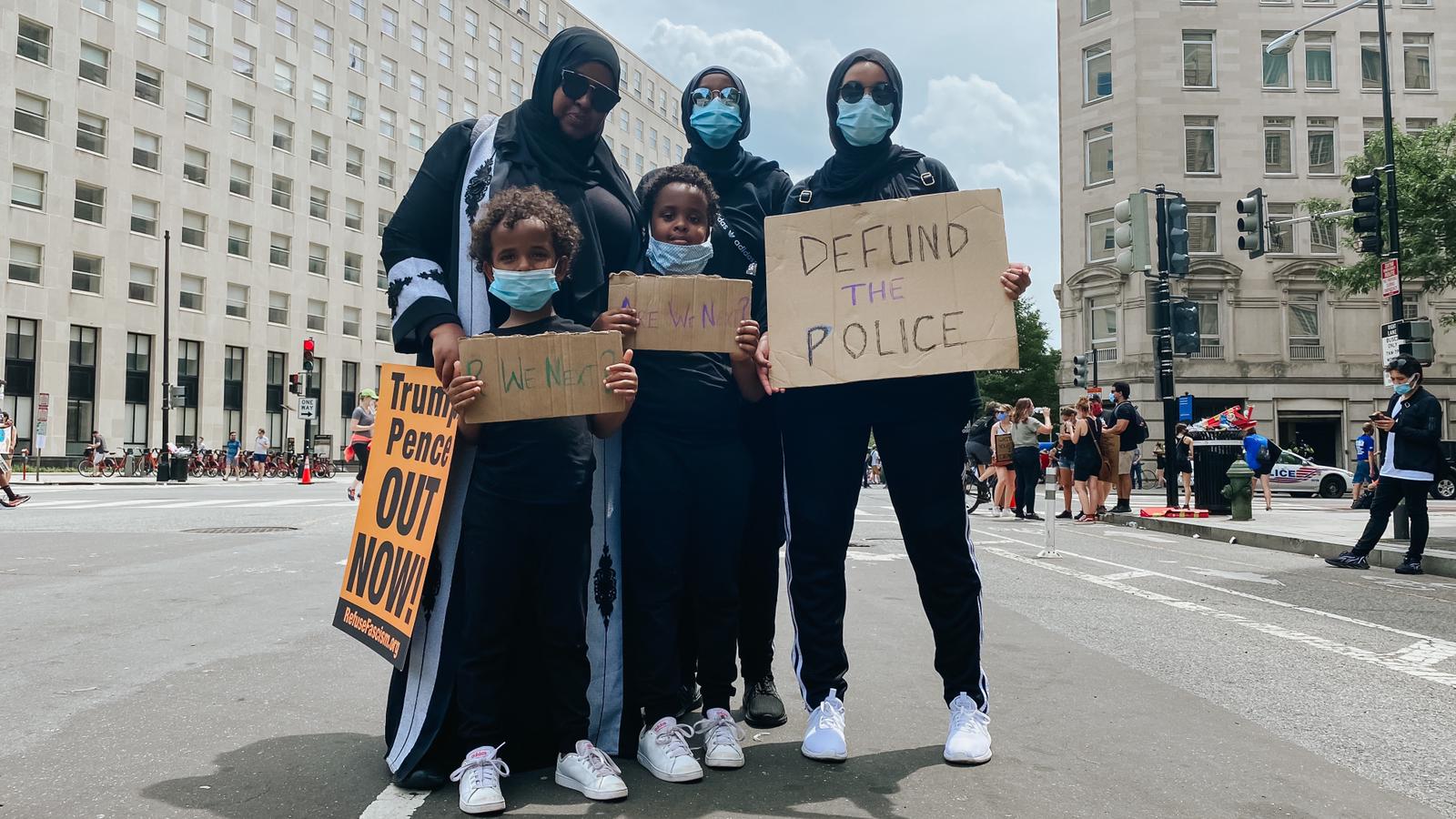

Walida Mukhtar, of Fairfax, protesting near McPherson Square on Saturday, June 6:

“Islam calls for justice. It tells us to go ahead and be on the side of justice. We’re always against the oppressor, even if it’s our own family. That’s a verse in the Quran. Even if it’s against your parents, your children and even against yourselves. Rise for justice. So that’s what we’re doing. This is worship for us, standing up for justice in the form of worship for us.”

Jamaal, a D.C. resident who declined to give his last name, at the Peace Monument by the U.S. Capitol on June 3:

“I don’t condone violence and destruction. I don’t condone rioting. I don’t condone the destruction of one’s neighborhood or property. But as a black person in America, with experience that I have, I can’t condemn it either. That’s something that is inevitable, I think, when you refuse to listen to people screaming for years that they need help, that there is a problem, that there is something unjust.

I have to turn to Twitter and get called a thug and get told that the president of the United States, the head of the country that I live in, would have let dogs loose, and ominous weapons to quote him, but we have people down in Charlottesville, Virginia, driving cars through crowds. We have people down in Charlottesville, Virginia, with tiki torches basically saying to keep our country white, only to hear from our president ‘there’s good people on both sides.’ So there’s definitely something wrong.”

Sheldon, of Hollywood, Md., who declined to give his last name, at Black Lives Matter Plaza on June 7:

“I think we need to make it harder to be a police officer and easier to be black. I think that’s the first step.

For whatever reason, this time feels a bit different than in the past. There’s been a lot less victim-blaming in this case and a lot more outreach… I’m cautiously optimistic that this will bring change.”

Nay, of Arlington, who declined to give her last name, on June 3 near the intersection of Connecticut Avenue and H Street NW:

“I have a young nephew who I’m literally seeing when I see a black man get killed. Who I am seeing when they incarcerate the wrong people. Who I am seeing when I see police harass others. I feel it’s my responsibility to stand up for him.

We are not just fighting for George Floyd. It’s every other unnamed black man who is killed daily. It’s every other black woman is killed in her house.”

Reginald Guy, a D.C. resident, at Earl’s First Amendment Grill, a pop-up grilling station by St. John’s Church, on June 6:

Guy began grilling $50-worth of hot dogs by Black Lives Matter Plaza on June 3 with one other person because he noticed as a protester that “I came out here, I was hungry, they were hungry, and that was a reason to go home.” He brought chairs because “I was standing and I was tired of standing and I wanted to go home and I was like, ‘If this is making me want to go home, I know I can do something to help right there — food and chairs.'” The operation swiftly grew, with more volunteers hopping on board to help and people bringing food and equipment, as well as contributing funds online.

Guy says that if President Donald Trump walked across Lafayette Square to talk to the folks at Earl’s, “I will give him a burger. What’s more American than sitting across the table, playing cards. C’mon bro, he would win America back if he came over here and played Uno with me. Soon, the police aren’t going to be able to tear gas because there’s going to be people in peaceful postures. The most peaceful posture is sitting at a table in a chair.”

Jordan Michel, a D.C. resident, at the Peace Monument by the Capitol Building on June 3:

“The protests — there’s a recurring trend in this country, its uprising, the demanding of rights, its peaceful protests, turns to rioting, it turns to violence, and then we get a response. And it’s usually a knee-jerk response, usually ‘Oh, we’re going to do something.’ And we’ve seen it in the past couple of days. We make noise, and then someone finally gets arrested, we make noise, and someone finally gets charged. We watch people burn and loot and whatever, there’s destruction, and then to appease us, we get handed something. But it’s a crumb. We’re asking for a loaf of bread and we get a crumb, and they’re like ‘Look, we fed you,’ but no, this is not sustenance.

The marches call attention, they’re what we need. What we need after that is sustained action — sustained visibility, sustained action. It’s what helped us during the Civil Rights Movement, it’s what we need now. And that requires getting lawmakers to actually listen. The prosecution is great, but we need actual changes in the system.”

Warren, a protester who prefers to go by her middle name, after she hid in a Swann Street basement on June 1:

“Out of nowhere, I just heard bang, bang. And then I heard the cops start screaming, ‘Move, move, move.’ And all of a sudden, people just started running from both ends of the street because the cops had started closing in from both sides. … So the woman, I mean, she threw open her basement apartment door for us and just said, ‘Get the fuck in the house!’ And we pulled in any anyone we could get, like we grabbed everyone we could off the street. It was about maybe 15 or 20 of us in that basement — in like a tiny little apartment. And we just slammed the door shut, locked it, turned off all the lights, and pulled the blinds closed. But we could hear and see everything through the silhouette of the curtains that was happening outside. And the things that I saw and heard are things that will haunt me for the rest of my life. They were arresting people right outside our window. We could literally hear bones breaking from being hit with police batons. We could hear people screaming and begging for their lives. I mean, it was it was literally like a war zone. … And we just sort of had to sit there as quietly as possible.

The police tried to intimidate us out all night. They tried. I mean, they had sirens. There was a police helicopter above us the whole night. We didn’t know what was going to happen next. We were hearing conflicting information about, like, were they going to start raiding the houses? Were they even going to let us out at 6 a.m.? We had no idea what was going to happen. We saw them shining flashlights in windows.

I mean, I’m Jewish, and I thought back to my history, my family who was hidden from the Nazis for months before they were exterminated. And I just thought about that experience. And that’s literally what I imagine it must have felt like.”

Virginia Telamour, of D.C., speaking at the Next Steps rally by the African-American Civil War Memorial on June 7.:

“You see the BLM paint on the road, right, and that’s awesome. It’s also great to see the sign. But I’m also wondering, after that, what are we doing to implement change?

I went ahead and emailed the D.C. Council to tell them that we need another grocery store in Ward 8. I live in Ward 8, Anacostia. We have that Safeway and that’s about it. … We don’t have a real hospital. It doesn’t make sense. So I emailed, and I’ll be passing that email to my friends, and telling them to email, because there’s strength in numbers.”

Kai Gamanya, of Silver Spring, an artist who hung a painting of a black power fist on the White House fence on June 7:

“This fence is representing that you cannot get to us. Basically, it’s the guy in power saying, ‘You can’t get to me.’ But now with the wall and the mural and everything, it’s kind of like the Berlin Wall before they took it down, everybody had to put stuff on it to represent, like, we are here for a cause, we are here to fight for something that’s dear to us, dear to everybody.”

Monica Curca, a D.C. resident, at Black Lives Matter Plaza on June 6:

Curca is part of an art collective that organized a lively drum circle by the White House, and brought a series of large banners to the plaza along with permanent markers, so demonstrators could write their own messages and draw designs on them.

“We call it peace activation. … There are intangible human needs, like belonging and creativity, and so this is really trying to bring that to the space and the community. We have the drum circles, we have four different banners, and we just wanted to create a space where people can be creative and really think of a new way how to work together.”

By the time we spoke with her, some of the banners were already on the White House fence, and at least two were folded up near the drum circle. As soon as Curca unfurled the banners, a crowd gathered. “Dope! That’s really cool,” said one person as the image of George Floyd emerged. “Wait, I can write on it?” Within minutes, a handful of people were crouching down next to the banners with a permanent marker in hand, adding their piece.

Keyone Carr, a D.C. resident, at Black Lives Matter Plaza on June 7:

“My cousin Assham, he did deal with mental health issues. He was in the middle of a mental episode when this all happened, which I think has made it easy for people to justify how he died. He was killed, shot multiple times by the police.

And the way the media portrayed it was that he was a suspect going after the officer’s gun and killed in that struggle, which is not how my cousin saw, who was there. And it wasn’t what the autopsy showed. And so it’s been covered in controversy. And so I feel like we’ve never been able to really say his name as part of all of this, right?

There’s so many of these other cases and issues where you were like, ‘OK, well that seems justified this way or that way.’

There’s a lot of assumption of guilt. There’s a lot of people being able to justify these killings or the brutality, and there’s just so much that goes on every day that gets excused away. That can’t be anymore. That shouldn’t be. And my cousin’s case, people should be just as angry and upset about it, as you are with George Floyd.”

Jonathan Blackmon, a master’s student at American University, at Black Lives Matter Plaza on June 3:

“The first day I came out here, I was seeking peace and reconciliation in my heart, being an African-American male … and I found it that day.”