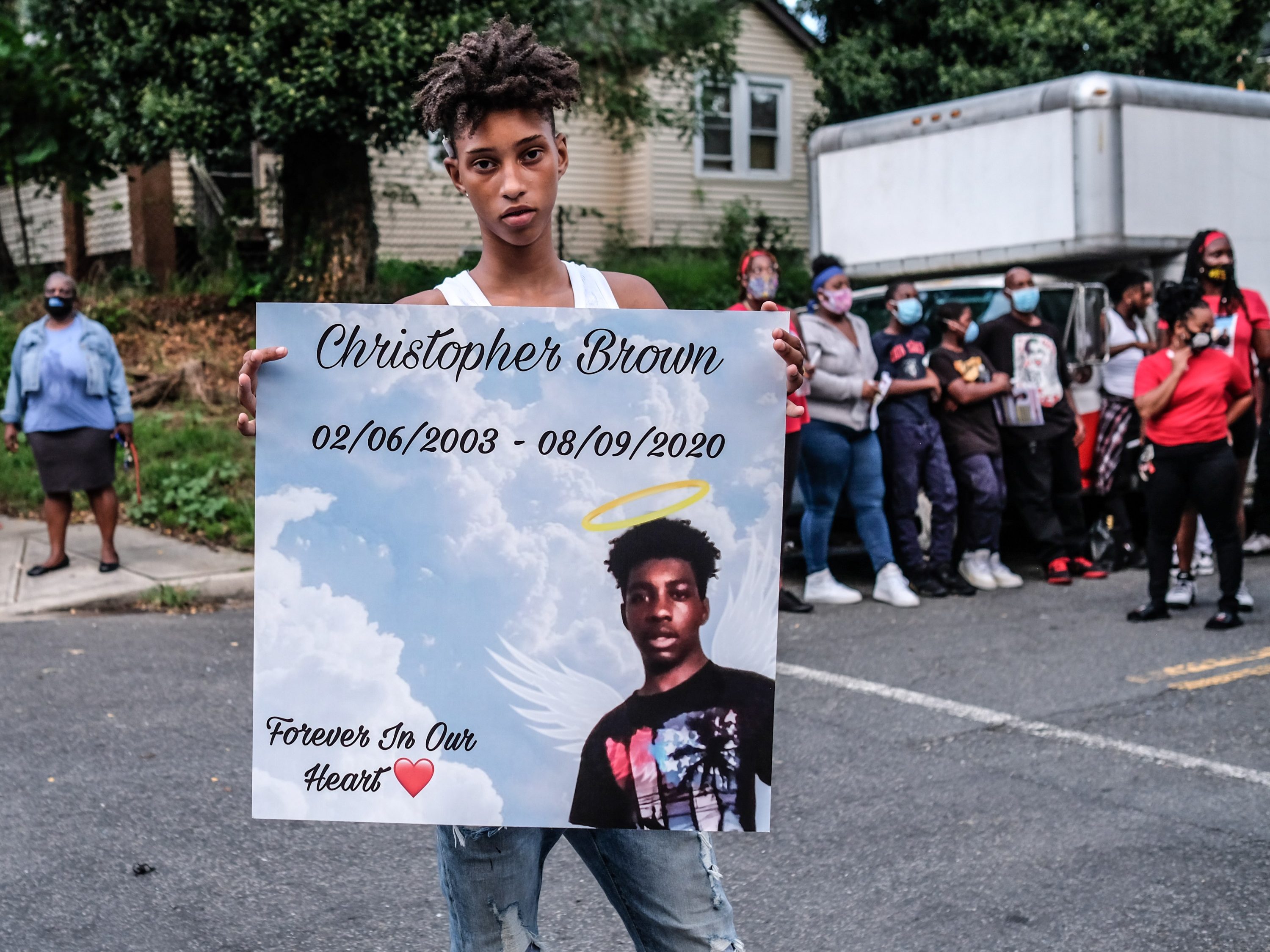

The crowd at Christopher Brown’s vigil in Southeast D.C. on Thursday night gasped as a rainbow appeared over their heads.

“He’s home,” a few mourners said as they looked up, and the crowd of several dozen turned toward the sky.

Brown was 17 years old when he died Sunday morning. He was at a block party in the Greenway neighborhood when, shortly after midnight, multiple shooters fired at the crowd, according to police. At least 21 others were injured; D.C. police chief Peter Newsham said he could not recall another instance in his career where so many people were hit by gunfire at once.

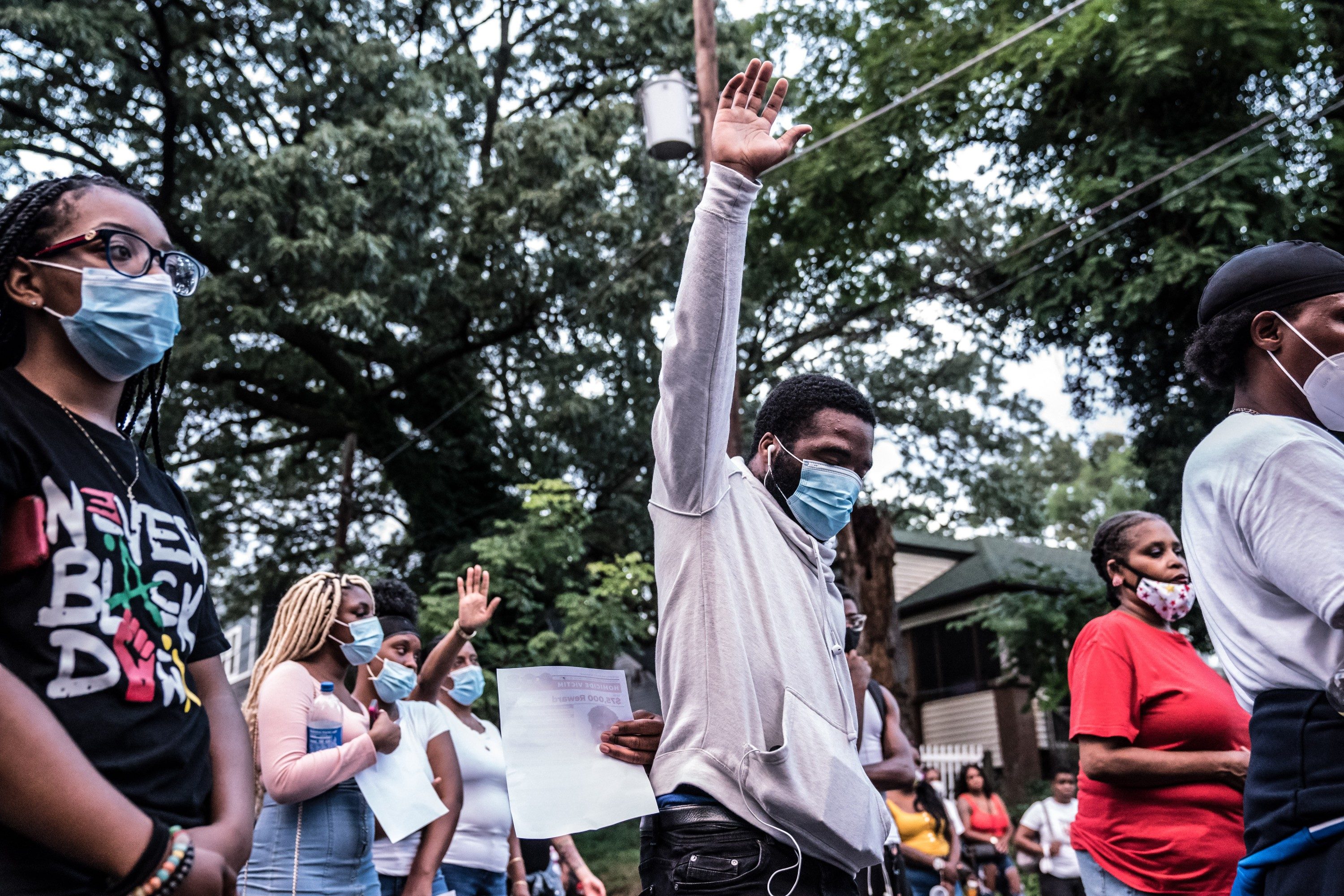

At the corner of 33rd Street and DuBois Place Southeast, the same block where Brown was killed, his friends, family, and community members gathered to remember him with speeches, candles, and a balloon release. Police blocked off the surrounding streets and moved through the crowd to pass out flyers advertising a $75,000 reward for information about Brown’s homicide.

Patrice Brown, Christopher’s grandmother, referred to him by his nickname as she began an emotional speech to the group of about 70 people. “I see Popi had a lot of friends,” she said.

Brown sobbed as she tried to convey the depth of her loss: “I’m so hurt. I’m really fucked up. I’m really, really fucked up. Nobody understands … you raise a child for all these years to be taken away.”

On the day of her son’s killing, Artecka Brown told WUSA9 that “words can’t explain who he was.”

“I don’t know where to begin,” she said.

Brown’s family says he was known for his sense of humor, and for being an amazing dancer. During an interlude between speeches at the vigil, young people showed off dance moves of their own as a tribute.

Brown’s smile “would light up the room,” said Antione Tuckson, his 35-year-old second cousin. Tuckson said he was like a father figure and mentor to Brown.

“About eight hours prior to him being killed, he and I had a very interesting conversation where he said … he wanted to do better and make a change in his life,” said Tuckson. “Those were the very last things that he said to me, and I was going to make sure I was there, to be there to help push him and motivate him.”

Brown leaves behind a one-year-old son and another unborn child, according to his family. He has four younger brothers.

“One of his brothers, when we first heard the news, for about 12 hours straight, he couldn’t stop crying, because of the level of influence Christopher had on them,” said Tuckson. “They still have to figure out and process this loss.”

Several others who had lost children in their lives to gun violence attended the event. Mike D’Angelo, whose niece Makiyah Wilson was killed by gunfire in 2018 at age 10, addressed the crowd and then gave Brown’s mother a painting of Christopher.

“I’mma do my part, the best way I can, to take his legacy across the world,” said D’Angelo, who recently returned from his third annual walk to Philadelphia in honor of his niece and other children killed by gun violence.

John and Wanda Ayala, whose 11-year-old grandson Davon McNeal was killed by gunfire on the Fourth of July, also attended the vigil.

Brown is one of 120 people to die by homicide this year in D.C., where homicides are up by 21% compared to this time last year. Most of the homicides have been gun-related. Brown’s family and other speakers repeatedly pleaded for his death to spur some broader change.

“Lord … help the death of Christopher raise up a leader in this community,” said Rev. George C. Gilbert Jr., who led a prayer at the event. “Help the death of Christopher change somebody’s mind to do right instead of doing wrong.”

Jawanna Hardy and Kayla Moore of the organization Guns Down Friday brought snacks, water, kids’ school supplies, and pandemic-related personal protective equipment to hand out. Their goal was to support Brown’s family, and connect those who were hurting from the trauma with the proper resources.

“These kids really need someone to talk to,” Moore said. “They need therapy. And many of them have asked for it, but they don’t know that that’s literally what they’re asking for. And just a safe place. A lot of our kids always ask for just a safe place to go outside.”

But for Moore, supporting children and families on an individual level is not enough. She says she wants to see sweeping, progressive action from local politicians to bring more resources to communities in Southeast.

“We really need to start looking at the policies and the people we elect,” Moore said, adding that she feels gun violence is exacerbated by “a lack of resources, and … a lack of elected officials ready to provide those resources.”

Nee Nee Taylor, an organizer with the D.C. chapter of Black Lives Matter, closed the evening by leading a chant based on a famous letter written by Assata Shakur.

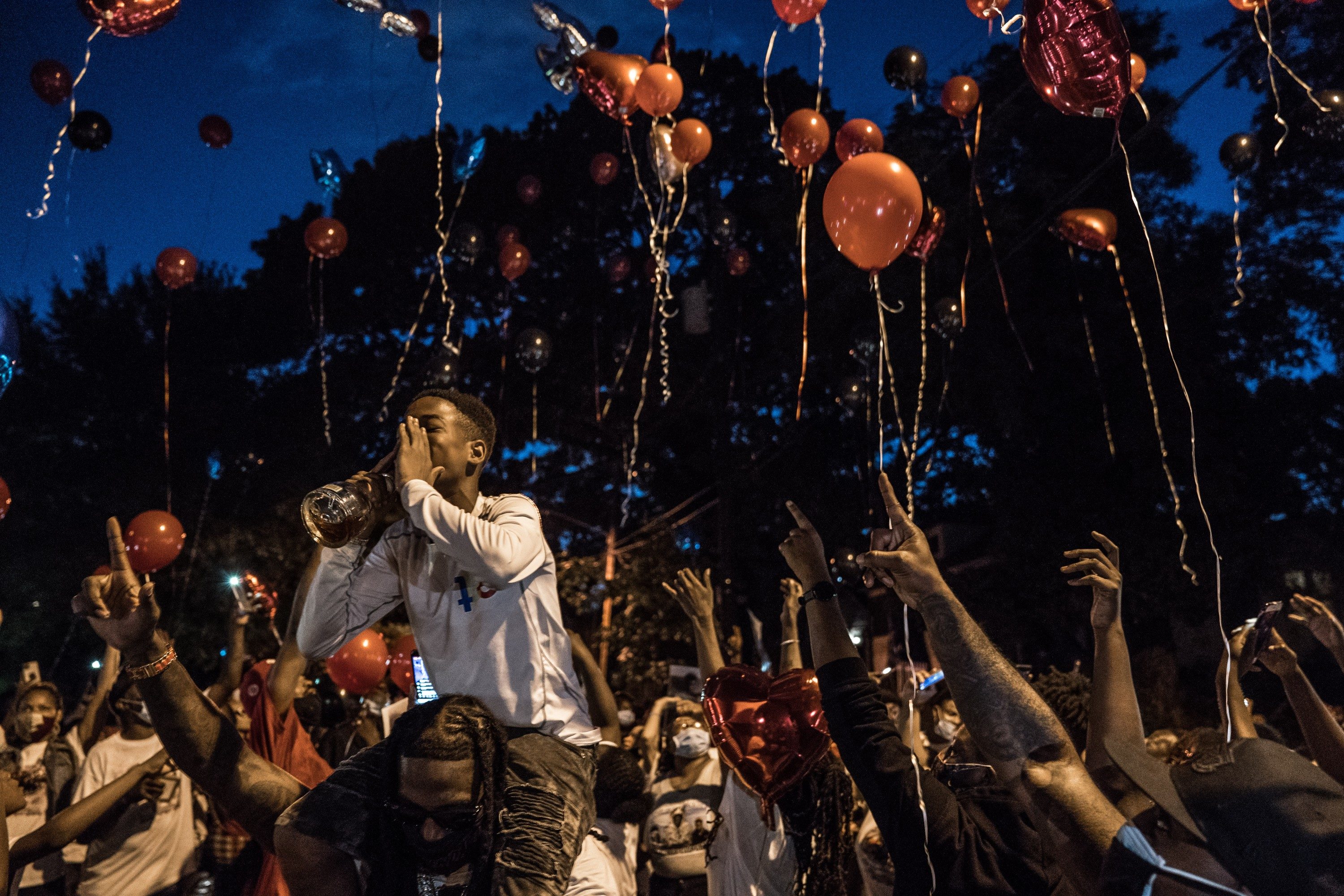

“We have nothing to lose but our chains,” the crowd chanted. They repeated the phrase three times, getting louder each time. On the third repetition, everyone released their red and black balloons into the sky.

Jenny Gathright

Jenny Gathright Dee Dwyer

Dee Dwyer