The coronavirus pandemic has inspired a number of rent strikes in the D.C. region, including in one of the city’s largest and most notable buildings.

On Saturday afternoon, about 20 of the roughly 2,000 tenants of the Woodner marched from the massive building’s lobby down 16th Street, along the border of Columbia Heights and Mt. Pleasant. They stopped when they got to the home of the building’s manager, Joe Milby, where they tried to present a list of their demands.

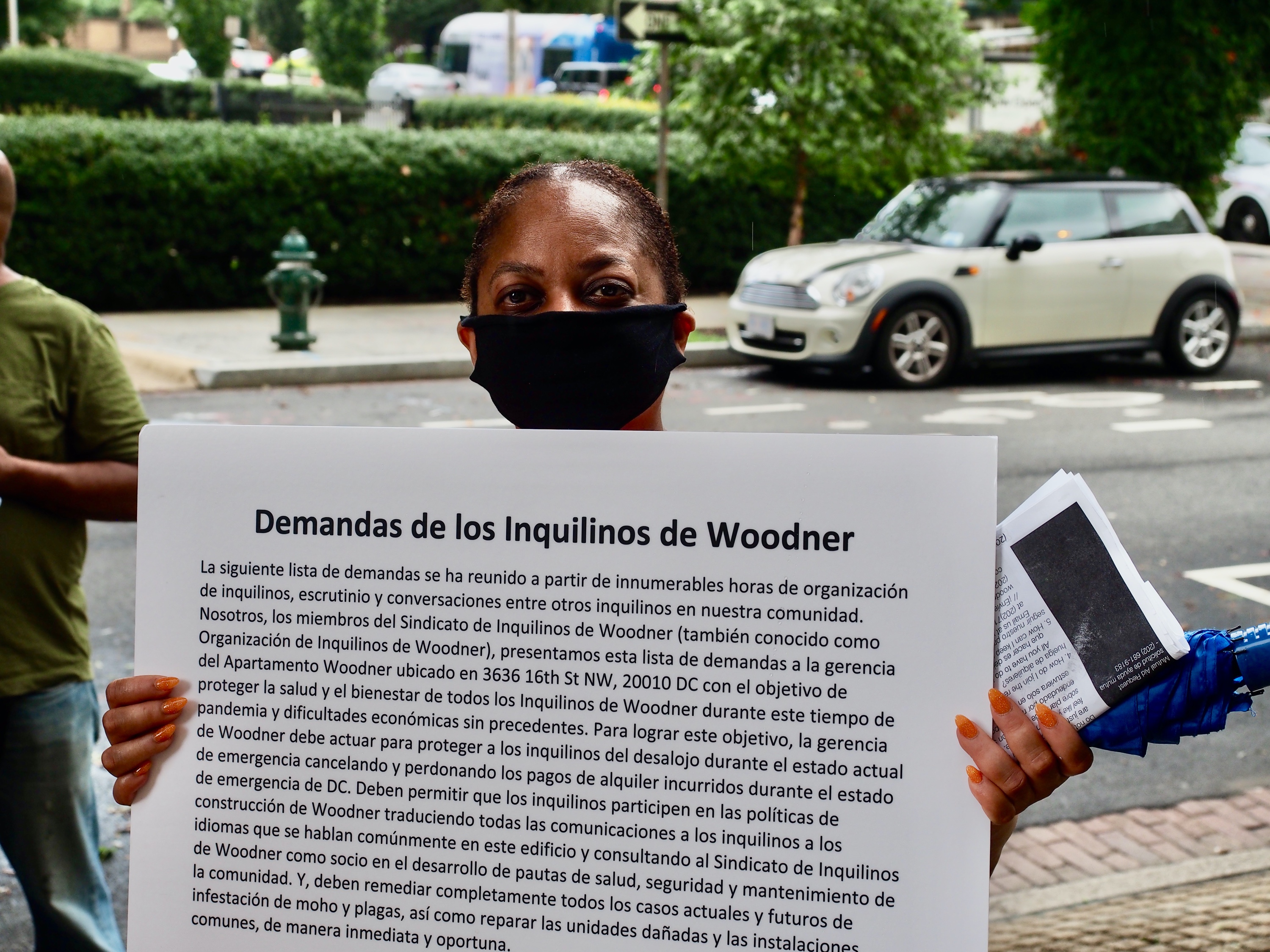

The residents want Woodner management to cancel and forgive rent until three months after the state of emergency lifts in D.C.; to make building announcements available in multiple languages (many residents are immigrants); to negotiate with the Woodner Tenants Union; and to address residents’ health and safety concerns regarding COVID-19 and what several tenants say is a significant mold problem.

“There’s mold in my apartment,” says Saunya Connelly, who hasn’t paid the $1,200 rent on her studio apartment in two months. “They tried to paint over it and the paint buckled after one week. I have strange rashes that are fungal rashes and they usually come when I start turning on the air conditioning. My doctor thinks the mold is causing these strange fungal rashes.”

The rent strike began in March at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and has grown as the D.C. Tenants Union has helped to organize renters. The union estimates 100 to 150 Woodner tenants are now withholding rent.

Some strikers have been unable to pay their rent due to the economic crisis brought on by the pandemic. Others say they can pay, but are withholding payments in solidarity, to push management to meet their demands.

A Woodner employee said no one with management was available to comment.

D.C. landlords are required to offer rent repayment plans to tenants who have seen their income dwindle during the pandemic. Property managers have said they don’t want to evict tenants—a costly, time-consuming process—but they need the revenue to maintain their mortgages and keep buildings operating. Many tenants, however, are hesitant to agree to take on more debt during a time of catastrophic unemployment.

“The building is offering payment plans, but a payment plan isn’t gonna cut it in this case,” says Nick McClure, a tenant who is withholding rent. “If you owe six months of back rent and you could barely pay your rent before, a payment plan will in you to this building for a really long time, maybe forever.”

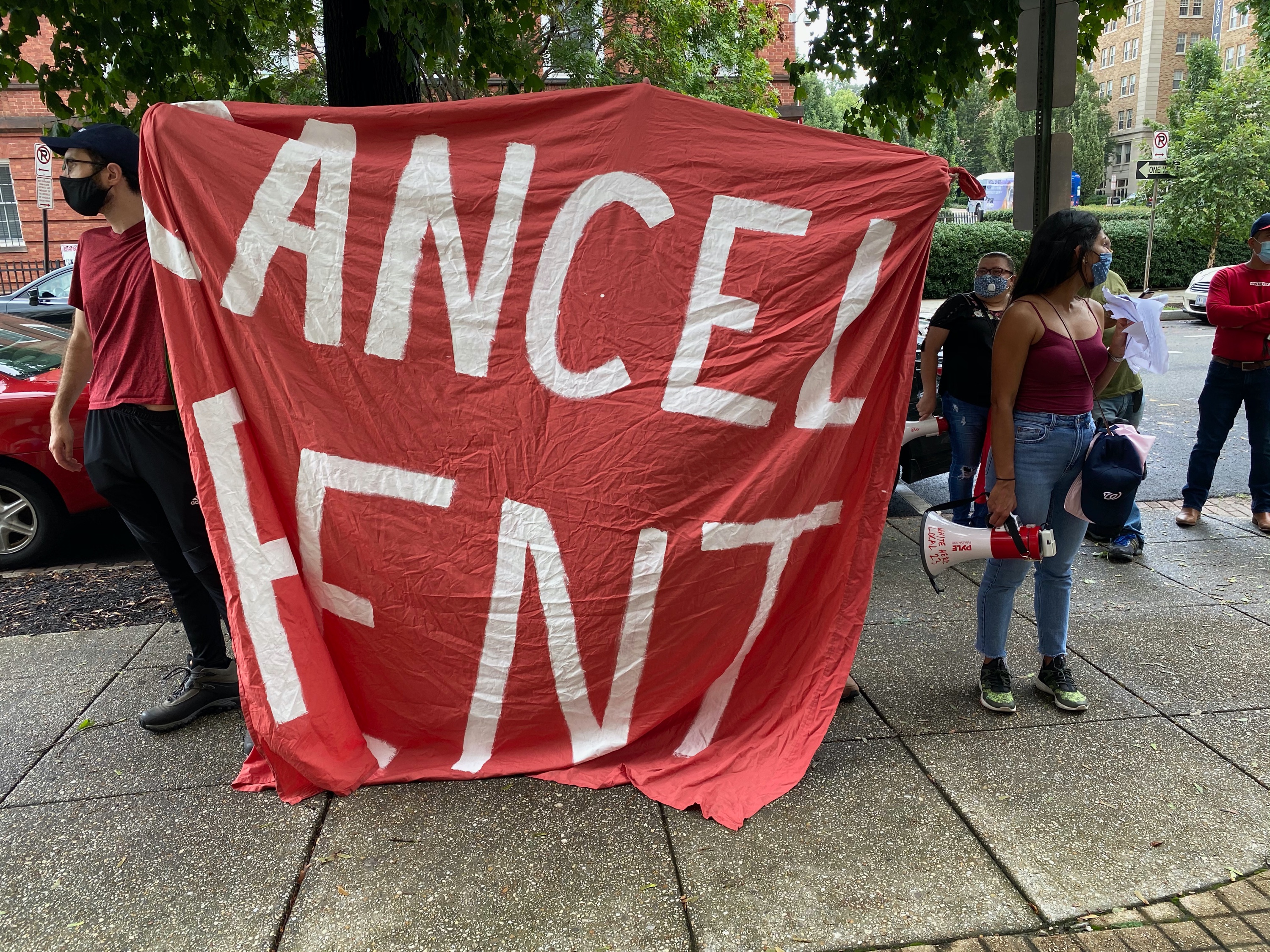

As they marched, tenants, escorted by police, blocked traffic for several blocks and chanted in English and Spanish, calling for rent cancelations and a continued ban on evictions. Even though evictions are momentarily frozen in the region, they will likely come roaring back as the pandemic lifts, unless some action is taken.

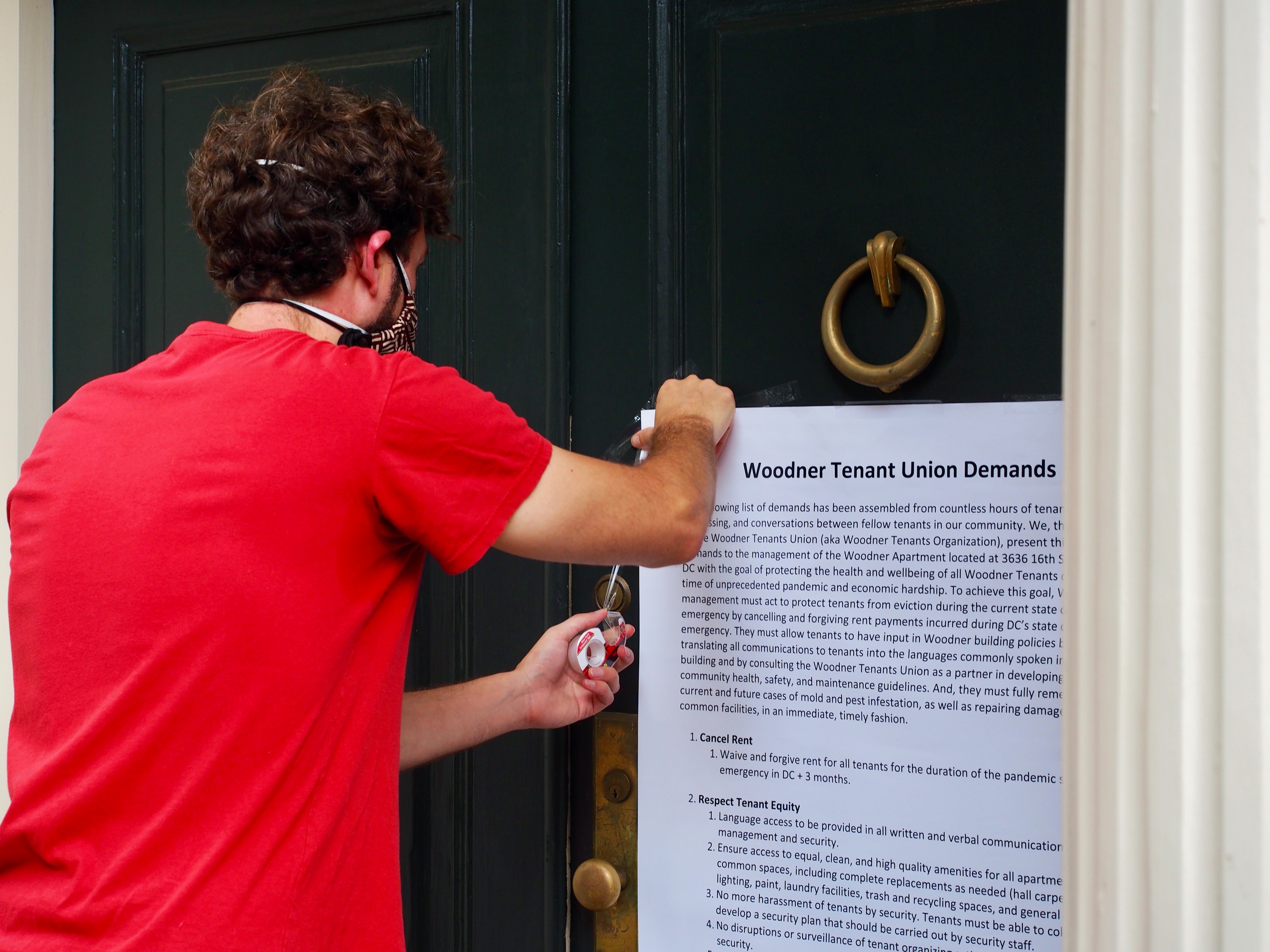

Outside of Milby’s home, strikers held up a red-and-white banner that read “cancel rent” and called for Milby to come out to talk. It wasn’t clear if anyone was home, so tenants taped a list of their demands to the door and gave speeches through a megaphone.

“From now on, we’re going to make their lives uncomfortable until they come to the negotiating table with us. Because the lives of everyone in our community are about to get a hell of a lot more uncomfortable if we don’t win,” said one resident who declined to give his name.

“If they don’t listen we’re going to come back,” he said, as the group broke into a chant of “We’ll be back.”

The Woodner opened in 1951 with apartments, hotel rooms, a grocery store, a restaurant and various other luxury amenities. The “city within the city” evolved over the decades, retaining some long-time tenants but gradually reflecting the diversity of the neighborhoods surrounding it. Now, many tenants fear this behemoth may be swept in the same wave of gentrification that’s engulfing those neighborhoods.

Tenant organization has been growing in the D.C. area, and the pandemic has fueled activism that was building for years as the city became increasingly expensive. Rent strikes in Brightwood and Columbia Heights saw tenants withholding their payments due to decrepit conditions in their units. Now, as the nation remains mired in both an economic and a public health crisis, tenants are increasingly speaking out, not only by withholding their rent, but also by protesting in front of landlords’ and lawmakers’ homes.

Tenants of an apartment complex in Alexandria who have been striking since March have visited state senators’ homes pushing for legislative solutions to the crisis. Activists banded together to block an eviction in Prince George’s County. And a Black Homes Matter rally in D.C. highlighted the urgent need for attention to housing in the District.

“We’re going to continue to escalate until that until they’re until they are willing to come to the table and negotiate with us,” says Sierra Ramirez, who has lived at the Woodner for two years, but hasn’t paid rent since May.

As the rally in front of Milby’s home concluded, the tenants walked back to the Woodner. They dropped lists of their demands into the slot where tenants typically deposit their monthly rent. A few neighbors who hadn’t been part of the march joined in.

Gabe Bullard

Gabe Bullard