This story was updated on Sept. 18 at 11:31 a.m.

In June, Sam Ressin read the news reports of protests against racism and police brutality in Minneapolis. Then he looked at his own community of Vienna, in Fairfax County.

The town was about to build a new, $17 million police station. It had already spent about $2 million finalizing a design. But across the country, calls were growing to defund police and allocate money to other services.

The idea of fighting the project seemed scary at first, Ressin says. But then he asked himself: “What right do we in Vienna have to say ‘No, we’re exempt. We’re exempt from critically reexamining how we do things, we’re exempt from having to have uncomfortable conversations’?”

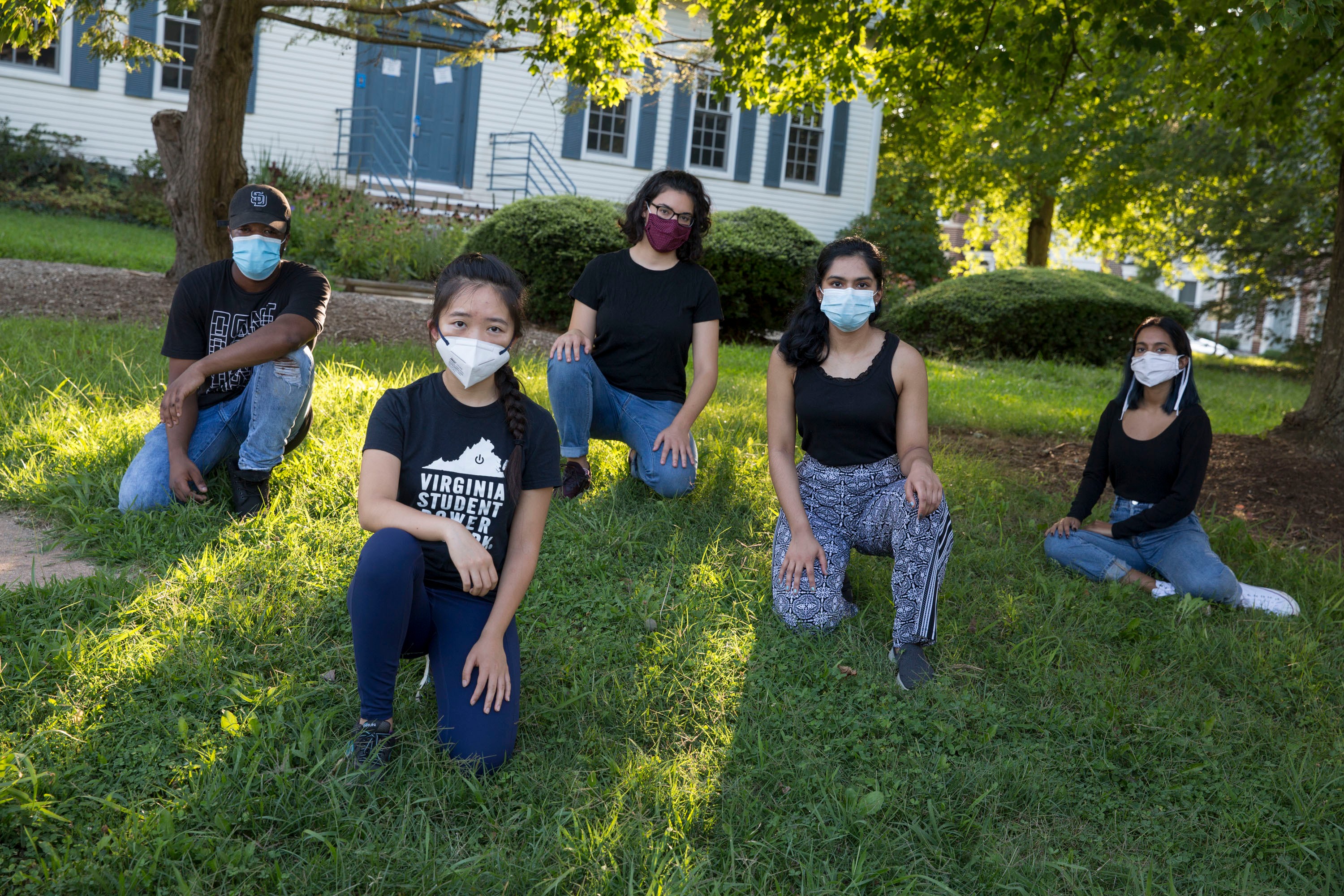

Ressin, a recent college graduate and an alumnus of James Madison High School in Vienna, soon discovered that several other alums and current students at Madison were also looking for a way to respond to racial injustice in policing. About 40 young activists—all affiliated with James Madison, though some now live outside Vienna—started getting on late-night Zoom calls to talk about policing in their town. They called themselves Wake Up Vienna.

Vienna is a quiet town of about 17,000 people. The population is 69% white, 14% Asian, 9% Hispanic or Latinx, and just 2.7% Black, according to 2019 U.S. Census estimates. About 40 officers serve on its police force, which also receives training and support from Fairfax County police. In 2018, 90% of Vienna residents rated police services as excellent or good, and 97% said they felt safe in the town.

The young activists thought of their town as a liberal, even progressive, place, one that might be open to the argument that law enforcement is structurally racist. They saw cities across the country and other places in the D.C. region making changes in police funding and structure, and they thought they could bring some of those changes to Vienna.

But they discovered that even proposing a commission on policing in their small, safe, mostly white suburb was fraught. At times, instead of debating what to do about racial bias in law enforcement, they found themselves making the case that racism even exists in their community.

A push for police accountability

By the time Wake Up Vienna formed this summer, the town government had already released a statement affirming support for racial justice. But the new group wanted to see an action plan to identify and address systemic racism.

They drafted a petition calling for a pause on the police station project, further community dialogue about policing, and a formal commission to engage with the community and write a report with recommendations for changes to the public safety model in Vienna based on resident input.

“The Town of Vienna has declared its solidarity with its diverse communities and its support for positive change, but words are empty without taking action,” the petition reads. “Now is the time for the Vienna community to critically examine, question, and reassess the roles, power, equipment, and funding given to law enforcement.” It now has over 1,600 signatures.

Members of Wake Up Vienna formally presented it to the Town Council in June.

Many local and national activists are calling for defunding — or even abolishing — the police. The Wake Up Vienna activists say they don’t necessarily want to go that far. They want to give their community a chance to reconsider the expenditure on the new police station, perhaps to reallocate some of the building funds and general police budget to mental health resources. And they argued for changes to create greater accountability, including collecting and publishing better data on policing, establishing a citizen review board, examining what it would take to give officers body cameras (proposals that are in line with the Fairfax County NAACP’s list of demands for county law enforcement.)

Vienna police arrested 280 people in 2019, according to internal statistics. The majority of them — 65% — don’t live in the town. The department recorded 13 use-of-force incidents during arrests in 2019, eight involving white people and five involving Black people. In the majority of documented use-of-force incidents, Vienna officers did not draw their guns. The department says it has never shot anyone in its 70-year history.

The group was alarmed to see that 31% of the arrests Vienna police made in 2019 were of Black people, which is not proportionate to the town’s Black population (2.7% Black) or the county’s population (10.6%).

The department began collecting data on motor vehicle stops this summer to comply with a new statewide law. But Wake Up Vienna would also like to see more statistics on all police interactions, not just arrests and stops, made available to the public.

Joyce Cheng, who attended the University of Virginia and is one of the original Wake Up Vienna organizers, said the accountability measures are forward-looking.

“It’s preventative,” she said. “It’s to prevent police brutality from happening in the future.”

In fact, the activists think their town’s relative safety make it an ideal place to experiment with new ideas about law enforcement.

“Because I think Vienna is relatively safe, and there’s data to support that, like crime rates, I think Vienna is a very well positioned town to be able to preemptively and proactively reconsider how policing is done,” Cheng said.

A new police station ‘is truly needed’

In early July, the council responded to the Wake Up Vienna petition, agreeing with the impetus behind it but refusing to pause the process of building the police station.

“We acknowledge and understand the unrest in the nation and the need and desire to bring about an end to racial discrimination and inequity,” the response said. “Vienna will continue to strive to be a community that welcomes and treats all people in a just and fair manner while celebrating our differences.”

“While we believe that a conversation on racial injustice must go forward, we do not believe that it would serve the ultimate goal of racial equality to delay the process of building a new police facility,” it continued.

The current police station, built in 1994, is bursting at the seams, the response said. There are not enough lockers in the women’s locker room for female officers. The investigations unit doesn’t fit in the station itself, and has to be housed in the Town Hall. There is not enough space to interview victims and suspects, and there is no dedicated community space in the building for Vienna residents seeking to file complaints or interact with officers.

Mayor Linda Colbert, who has served on the Council for six years, told WAMU/DCist the police station project has been on the Town Council’s list of priorities for two decades. (Colbert said the town struggled to fund and build the current station in 1994, and the facility was never fully adequate.) The town has been working to borrow money — at a good rate — for years to pay for a new building.

“You have to plan way, way out in advance,” Colbert said.

She worries a change in course so late in the game would hurt the town’s triple-A bond rating. And she notes that the idea of reallocating funding from the police department construction to other services like mental health and education is complicated, because the two exist in two different streams of funding. The police department project would be funded by money from the meals tax, which residents and visitors pay when they eat in Vienna restaurants. Social services — the ones not funded at the Fairfax County level — are paid for by revenue from resident real estate taxes from the general fund.

Colbert said the town has already gone through many stages of the planning process for the new station: Vienna hired an architect to design the project in 2018, and the plans have been reviewed publicly by the Planning Commission, the Board of Zoning Appeals, the Town Council, and the Board of Architectural Review. The public has received information along the way in the town newsletter, the Vienna Voice, and in local news outlet InsideNova.

Up until now, Colbert said, residents have been supportive of the building project.

“It really was not, I would say, until the George Floyd incident that we really did receive a lot more feedback,” Colbert said. “Horrific event, no doubt. There’s no minimizing what happened.”

The mayor said she agrees that every police department should review its policies and practices in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, though she believes the Vienna police have a different role and situation from larger city departments.

Colbert recently signed the Obama Foundation Pledge, which asks mayors to commit to review police use of force policies and seek community feedback. As a result, the police department reviewed and updated its policies to be consistent with the 8 Can’t Wait campaign, which recommends bans on specific use of force practices like chokeholds and shooting at moving vehicles.

“I think we’re very transparent,” Colbert said, noting that the department uses in-car cameras and that it already banned chokeholds.

“I’m not saying that that means that nothing will ever happen. Certainly not,” she said. “I don’t mean to say that, ‘OK, I’m satisfied’ and we’re moving on. But we haven’t had these issues.”

Little agreement about how to move forward

At a recent town hall, police chief James Morris answered community questions about his department’s internal investigation procedures, its diversity (the department is 15% people of color, but does not have any Black officers), and explained a comment in the Vienna Voice that officers “can’t lose a fight” in situations where force is necessary.

Morris said he and Colbert are working on putting together a community commission on policing, “a public safety committee with council, where maybe the mayor appoints a councilmember, I appoint command staff, we bring in a community member or two, and we review everything,” he said.

But Wake Up Vienna members argue that a police review of police policies isn’t enough, and they think a policing commission should be led by community members of color from outside of the town’s policing and political establishment.

“We kind of felt like one like having the police itself evaluate its own practices is not really good,” said Megha Karthikeyan, a recent University of Virginia graduate and one of the original Wake Up Vienna organizers.

Meanwhile, other Vienna residents believe all the community meetings and reviews of department policies are entirely unnecessary.

At the town hall, a white man in a t-shirt with the slogan “Blue Lives Matter” printed on the front asked the socially distanced crowd to give police officers a round of applause for their service. Another resident, who is white, said he felt the national narrative about policing was “one-sided,” and denounced politicians and the media for demonizing the police.

“Policing and law enforcement isn’t only about the police. The perpetrators have a responsibility to not resist arrest and cooperate,” he said.

“So my question is, what can we do as a town to protect our police from being demonized by politicians, the media, and certain people that seem to not like police?” he asked. “The second part of my question is, what are we doing to stop these claims of racism in Vienna? I find this very upsetting. I’ve been here 22 years, and I don’t think Vienna is a racist town at all.”

At times, Colbert seemed caught trying to balance the two perspectives in her answers.

“We’re not a perfect town like any other place in the world, so I’m sure there’s racism going on,” she said in response to one of the answers. “I grew up in this town. My family and I really have … just a lot of friends of different backgrounds, and so I really try to talk to people a lot, and I hope they feel comfortable coming to me.”

Even if their positions on policing differ, Colbert says she’s glad to see the Wake Up Vienna activists taking an interest in town affairs. “I do appreciate their passion. And that is sincere,” she said.

‘Now we have to explain this big systemic issue’

The members of Wake Up Vienna are continuing to push for change in policing, but after months of organizing, they’re less optimistic about the outcome than they were in June. The police station project is moving forward, with the town poised to award construction contracts and break ground this fall.

While the group still hopes to delay construction, their focus has started to shift to address the big challenge their advocacy has run into: Many of their neighbors don’t believe police in Vienna — or Vienna writ large — could be racist.

“It’s almost feeling like we’re hitting an even bigger wall, because now we have to explain this big systemic [racism] issue,” Karthikeyan said. “And if we can’t even get past that, it’s like, well, then how are you going to tie that to police? And so it’s kind of gotten to be a lot bigger than we thought.”

In the absence of a commission on policing, Karthikeyan said the group is trying to collect and publish anecdotes of residents’ experiences with police.

The first one alleges that a young Black person on the way home from the grocery store was questioned, profiled, and detained without probable cause by Vienna police, who also entered the person’s home without a warrant. (DCist/WAMU has reviewed video of the incident, which shows a chaotic and contentious exchange between the person, a family member, and two police officers.) At press time, a spokesman for the police department said an internal investigation has been launched, and Colbert said in a Facebook post that the town manager will be involved in the police review. (Vienna police closed the investigation several days later. In a statement, the department said it found the young person’s account of racial profiling “unfounded.”)

Karthikeyan said one of her big takeaways from the summer is “how important voting in a town election is.” She’s been surprised to find how far apart she and some members of the Town Council are on policing.

“Some people — they may seem very progressive, but they’re very, very pro police,” she said.

She and her fellow activists are settling in for the long haul. “We’re realizing that, you know, activism isn’t just something that you can just do as a project,” she said. “It’s something that’s ongoing.”

Even in June, Cheng said she saw value in the work, even if the police station gets built.

“I think that if the worst outcome of our project is that this initiates more conversations about race in Vienna, I think that would still be like a great, great outcome,” she said.

This story was updated to reflect that Joyce Cheng is 22 years old. It was also updated with the results of the Vienna police investigation into a social media account of racial profiling.

Margaret Barthel

Margaret Barthel