Lidel Smith is 82, and he’s never missed an election since he was eligible to vote. He says his grandfather, who couldn’t vote, drilled the importance of casting a ballot into him.

“Taught me to vote for my rights, ’cause he didn’t have no rights,” he says.

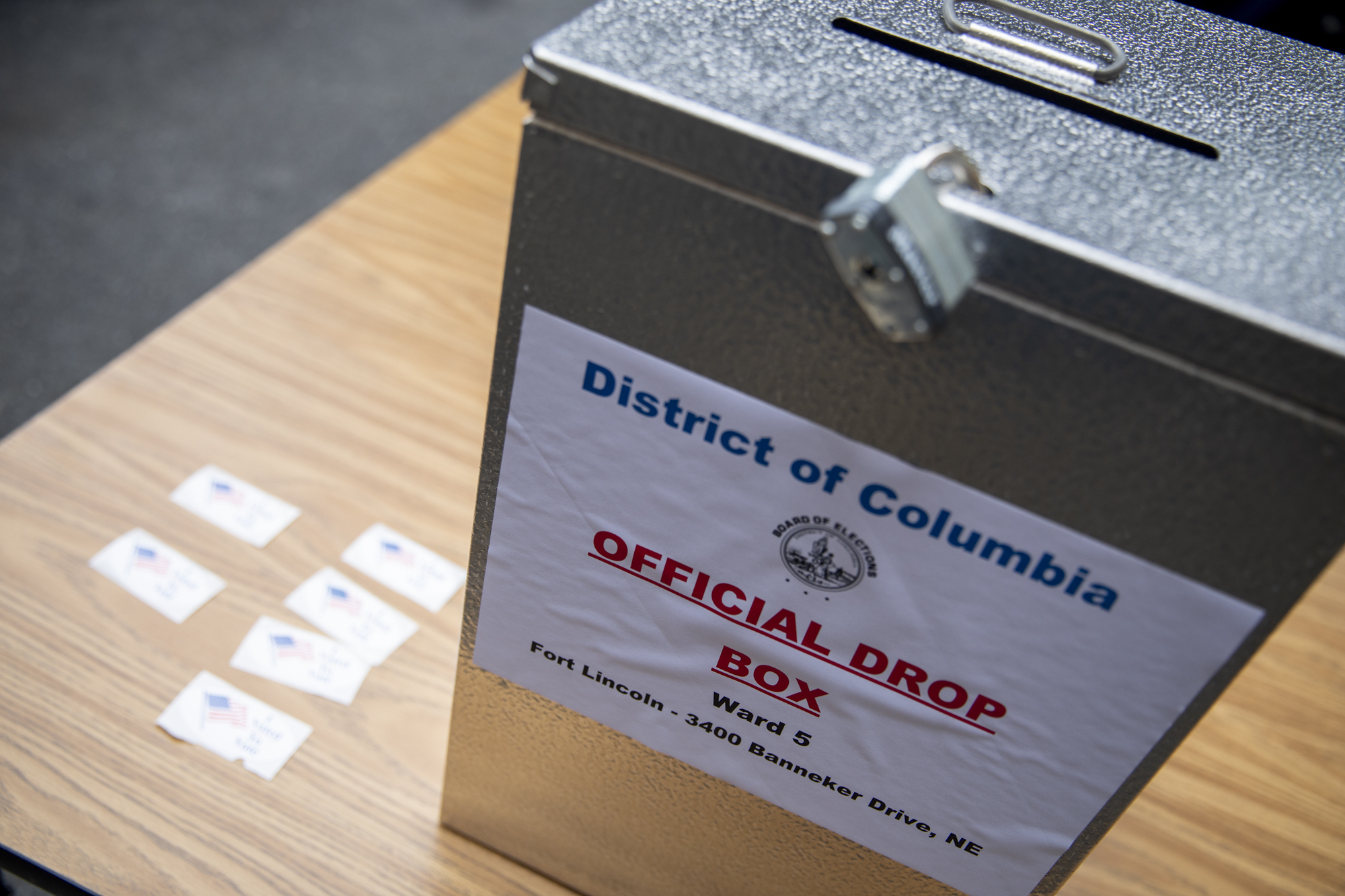

This year Smith didn’t have to wait until Election Day, travel to an early voting center or even find one of the city’s 55 ballot drop boxes. Instead, the election came to him. Two D.C. officials with a silver padlocked “Voter Container” came to his building where he popped his ballot in.

These containers — mobile ballot boxes, essentially — are the brainchild of Bob King, the guardian angel for senior voting in D.C. Helping seniors vote is personal for him. He says his mother died at 40 from complications with diabetes and his father died at 43. “I never had a chance to see my parents become seniors,” he says.

King says seniors are the most reliable voting bloc, but with concerns about COVID-19, many have been too nervous to leave their homes to cast ballots. And that, he says, is why the voter containers are so valuable. “The only public transportation for seniors would be the elevators, which simply means that they get on the elevator, come downstairs and vote,” he says.

King is a former ANC commissioner. For 40 years he’s helped the elderly fill out absentee ballots, organized meet-and-greets with candidates and provided transportation for thousands to go to the polls on Election Day. He would regularly coordinate more than 25 buses that would take seniors from apartment buildings, nursing homes and assisted living facilities to the polls across the city and back.

“The seniors are always ready to vote. Rain, sleet, snow. The seniors got to go,” he says. “I think the seniors live in history and it’s a testament to the struggle to vote and that’s been handed down.”

Ramsey Alwin, president and CEO of the National Council on Aging (NCOA), agrees. She says older Americans take their civic responsibility seriously. Programs like Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and the Civil Rights Act have been “significant game changers” in improving their quality of life.

Seniors make up about 17% of the population in the District. Many of them live in Fort Lincoln in Northeast D.C. and are particularly vulnerable. They are mostly African-American, and rely on public transportation and are on Medicaid.

In just one small area of Fort Lincoln, a small neighborhood located close to the border with Maryland, King points out five public or low-income apartment buildings, home to about 1,200 seniors. Over the years, King has collected detailed information about how many need what kind of help.

“The number of seniors who are in wheelchairs, the number of seniors who own canes. The number of seniors who were functionally illiterate. The number of seniors who were homebound,” he says, rattling off statistics on pieces of paper he carries with him. “Those numbers are staggering.”

This year going to the polls is especially daunting for seniors. During the city’s June primary, residents waited in line for hours because there were fewer polling places and social distancing measures had been put in place. D.C. officials have warned that lines could also form on Election Day.

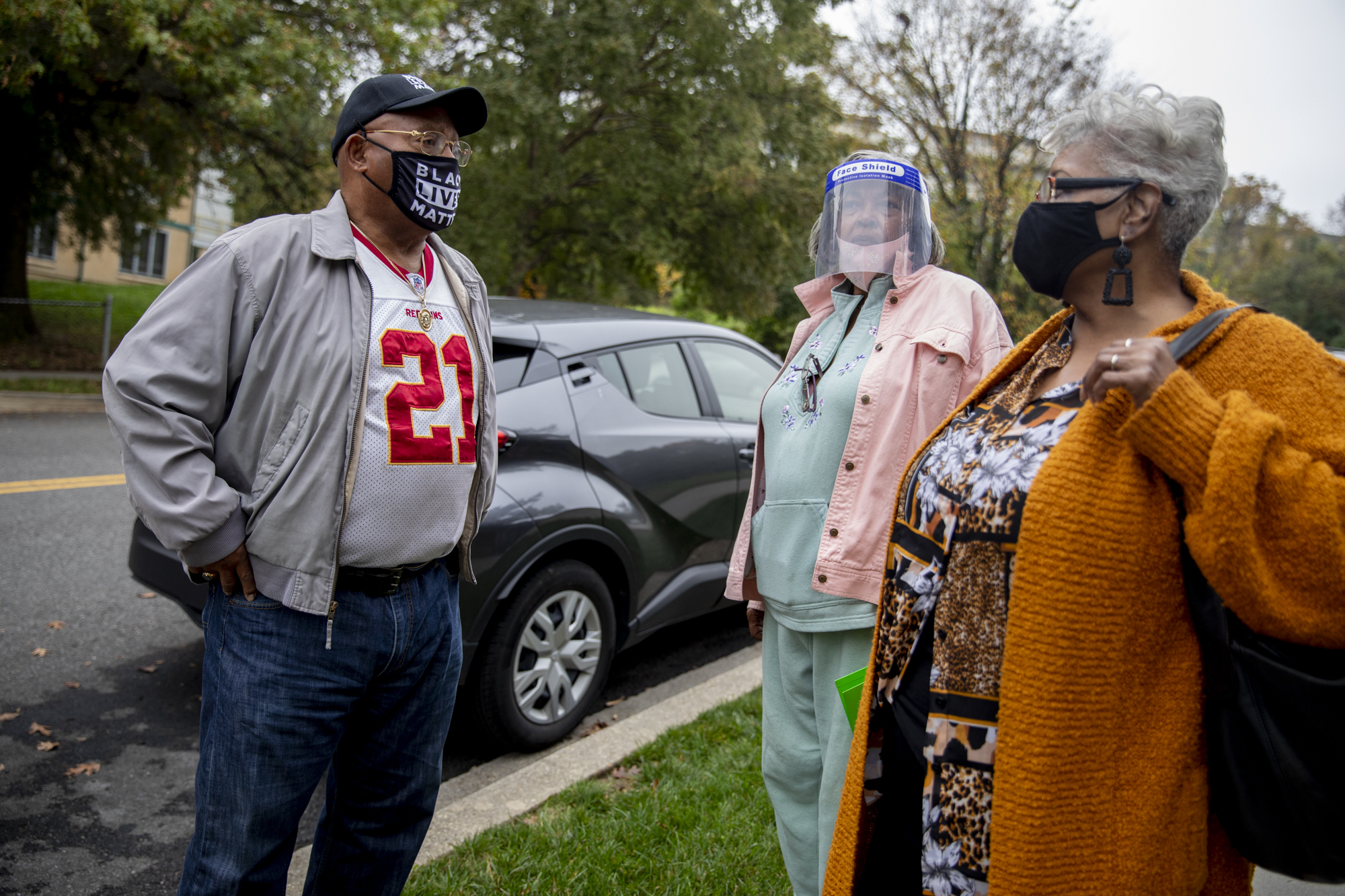

Seniors are also afraid of taking buses to the polls in case they’re crowded. Many, like Doris Foreman, have pre-existing conditions and are worried about going to the polls this year. “I have chronic bronchitis. I’m 69 and I’m just trying to stay prayed up and stay safe,” she says.

“It’s an overwhelming experience this year,” says Alwin.

But as good an idea as King’s mobile voter containers were, he and other senior voters say the D.C. Board of Elections didn’t properly execute them.

Linda Brooks, the president of the Tenants Association at Fort Lincoln Senior 2, home to 180 seniors, says the containers are a “great alternative,” but adds that she was never told about them. “The Board of Elections didn’t notify that they were coming to our building and we had no indication as to a time or anything. And no one trusts the mailbox,” she says.

Brooks says after President Trump tweeted, without any evidence, of mail-in voting resulting in widespread fraud, none of the seniors trust the Postal Service. So she’s been collecting ballots and dropping them off at poll centers every day.

King shared information from his years of transporting seniors with the Board of Elections in January. He says he’s frustrated that despite asking repeatedly, he wasn’t given information about when the voting containers would be in different buildings so he could inform his networks.

“One of the things that they failed to do is contact a manager. They did not put a notice up in the building. We have thousands of seniors citywide who cannot get to the polls,” he says.

When asked about King’s complaints, Nick Jacobs, a spokesman for the elections board, said notification wasn’t given because of security concerns. But he later changed his response.

“We undertook a very comprehensive effort to reach out to seniors across the city and in many, many cases they responded,” he says. “But in some instances, we didn’t hear anything back or we were not able to work with centers given the tight window.”

Diane Burton-Irving, a resident in Fort Lincoln, also had no idea about the voting containers. She uses a wheelchair and left her house at 6:30 a.m. to catch a bus to go cast her ballot three miles away, returning home four hours later. She says she was nervous about leaving the house because she’s had several family members and friends die of COVID-19. But it was a risk she had to take.

“I want to make sure that my vote is counted,” she says.

This story originally appeared on wamu.org