When we lose a loved one, we begin to treasure the things we have to remember them by. Some people save voicemails. Others save photos. When Cheryl Sanford’s son Emmanuel died, she had hours upon hours of video footage of him.

A decade prior, when Emmanuel Durant was 9 years old, he and his older brother, Smurf, met recent college graduate Davy Rothbart at a basketball court by Watkins Elementary School in Southeast D.C. Rothbart, who would eventually become a filmmaker, had just gotten his first video camera. He developed a friendship with Smurf and Emmanuel during their days at the basketball court and eventually started going over to their house for dinner. That’s where he met Sanford, Smurf and Emmanuel’s mother, along with their sister, Denice.

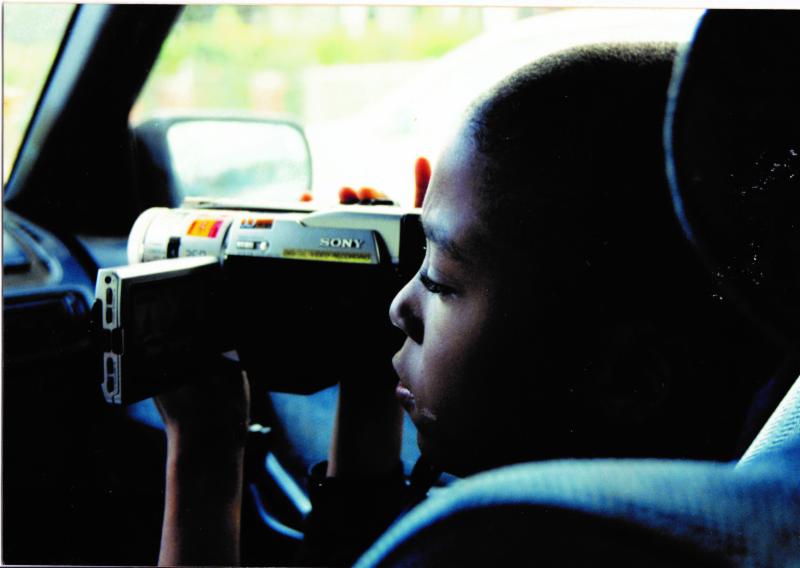

The group started filming interviews and footage of the neighborhood together, and Rothbart would also leave the family with his camera from time to time. Sanford says at first, the videos were just “home movies” they made for themselves.

“I started watching the footage that especially Emmanuel had been shooting, and he clearly had a poetic eye and he was capturing some really beautiful images, as were Smurf and Denice,” says Rothbart. “But there was no real plan.”

The family continued to film themselves for years. Rothbart moved out of D.C., but he remained close with the Sanfords and came back to visit over holidays.

In 2009, Emmanuel was killed by armed robbers in the family’s home. In the days that followed, the Sanford family began talking with Rothbart about how they could turn their many years of footage into a film. It was a way, Sanford says, of trying to make sure Emmanuel’s death could mean something.

“I have maybe a dozen girlfriends in the past 20 years who have lost sons … and daughters, too,” says Sanford. “And it just came to my mind that we had footage of my son from his childhood, from growing up. I just knew in my heart I could show people, ‘Look what you’ve done. This is what happened. You’ll get to know this person and you’ll just see that we’ve been robbed.’”

The project that resulted from that decision, the documentary 17 Blocks, is now streaming online via movie theaters. Its title is a reference to the distance between their home at 17th Street and Kentucky Avenue Southeast and the U.S. Capitol. (The family later moved to other homes in Northeast D.C.)

The film’s editor, Jennifer Tiexiera, whittled down 1,000 hours of footage that Rothbart and the Sanford family produced over the years into a 1 hour and 38 minute narrative arc. At the start of the film, Emmanuel is a charismatic, conscientious 9-year-old; 17 Blocks follows his life through his death at age 19, months after his graduation. The film chronicles his family’s grief, challenges, and triumphs in the decade after his death — like Sanford’s decision to start addiction treatment, Denice’s achievement of a new career goal, Smurf’s transition out of the drug trade and into steady employment at a grocery store, and the long healing process of Emmanuel’s girlfriend, Carmen.

The family does this all as they raise the next generation — Denice and Smurf’s children — and continue to process the loss of Emmanuel in this intimate and sometimes deeply painful look at the family’s life.

Director Davy Rothbart and Cheryl Sanford, the film’s producer and Emmanuel’s mother, spoke with DCist/WAMU about the process behind the film. This Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Do you remember a specific moment when you decided that this collection of footage that you had should become a film that the public can see?

DR: I remember just in those very hours and days following the shooting, having those conversations with Cheryl and with Smurf and Denice where Cheryl presented a vision, and I think we all immediately could see that. It means one thing to hear the number of people shot and killed in D.C. It’s another if you feel like you really know that person. We knew what footage existed, and we knew if somebody watched all that footage, they would know Emmanuel. They would know him from when he was a 9-year-old boy and they could watch him grow. And that loss that we were all feeling could be felt by someone who didn’t even know him personally, you know, and then by extension, they would understand in a deeper and more powerful way the loss of all of the hundreds of people, really thousands over the years.

The film also shows the other cameras that were present in the moment of your family’s grief right after Emmanuel was killed. It shows the man from the Washington Post who was in your house with a camera and the TV news footage. How do you think about the difference between what you were able to do with your own footage versus what was happening in the news immediately after you lost Emmanuel?

DR: The people from The Washington Post and and local TV news crews that we interacted with, they were utterly genuine and compassionate. They were doing their best to share this story in the best way they could.

Cheryl, you said something the other day that I thought was moving. Somebody said, “Was it surprising to you to see the finished film or as the film was coming to life? And was it traumatic, in a way?” And you said, “Look, this loss is felt every day, every hour we feel this loss.” So [the point of the film is] I think to give people that long view of like, hey, it’s not like this happens, and then when it disappears from the news, you move on. It’s something you continue to wrestle with, with ups and downs, over the weeks, months and years that follow.

CS: Not a moment goes by that I don’t think of him or think of what [he] could be right now. It has given me a purpose.

DR: And there are some great organizations now that we’re working with as partners on the film — because the idea is how can this story in this film be used as a tool for change? Using the film to help support those kinds of organizations is another goal for us. And Cheryl and I, as well as Smurf and Denice, we started an organization after Emmanuel was killed and we call it Washington to Washington. I used to always talk about camping and hiking, that I grew up doing that in Michigan. And I wanted to bring Emmanuel camping, hiking. And I regret I never had the chance to do that. But Cheryl said, “Why don’t we do it this summer? Just some of those kids that used to follow Emmanuel around the neighborhood, they looked up to him. Let’s give them that opportunity.” And the first year, we took maybe 12 kids from Washington, D.C. to Mount Washington in New Hampshire for a week of camping, hiking, canoeing, swimming. And it was awesome. And so we’ve done it every year since.

CS: It makes me feel as though my baby’s still here and that he’s doing something, you know, and it also gives me pleasure knowing that someone is benefiting from this — they wouldn’t ordinarily have that opportunity to do these things. I had never been camping before my whole life. It gives these children a chance to get in touch with nature and get a quiet moment to themselves out of the city and just see God’s world.

During all those years of filming, Cheryl, what was your relationship with the camera like? Were there times that you wanted the camera on — and times when you specifically wanted the camera to be off?

CS: A lot of times I didn’t even know that I was on camera. It just didn’t bother me because I didn’t visualize this coming to this [documentary]. Initially, it was just for my own purpose for myself, so it didn’t bother me. And when I saw the finished product, I was grateful that it was put together the way it was put together.

DR: One thing we talked a lot about as we were beginning to see it as a fuller movie is this instinct you had to keep it real and your courage really in sharing every aspect of your life. We had talked a lot about substance abuse and addiction, and you said to me one day, “You know, people need to see what it actually looks like to use because it’s ugly, I’m not proud of it. But they need to actually see what this looks like: Let’s film it.”

CS: That came about because, believe it or not, Denice, Smurf, and I had a conversation and they were like, “Well, I really didn’t know [you used drugs] until I got 16, 17 years old.” And I’m like, “How could you not know?” But that was one of the reasons why I said, “Let’s include it.” To show that these things get passed by or they can be missed, and [people] can get involved in something too easily without knowing what they’re getting involved in — as I did.

DR: Because it’s kept invisible, people often don’t know what it is until they’re in the midst of it as opposed to — let’s just put it all out there. Let people see exactly what this looks like. And I thought that was a courageous and wise decision for the film. It’s raw and it’s intimate, but it’s honest.

There were a thousand hours of footage. What are some things that had to be cut out of the film that you wish people could see?

CS: Oh, just more of Emmanuel when he was younger, just things that they did around the house. Think about it: Out of 365 days, he had [the camera] the whole summer when he first met Davy and from after that point, all of the school year. So he basically lived and breathed camera.

How did you all decide when it was done, and when it was the moment to stop filming and actually put the documentary together?

DR: When [Denice’s son] Justin and his cousins — when they got to be the age that Smurf and Denice and Emmanuel had been when I first met them, that’s when it felt like it had really come full circle. Now we have a new generation growing up pretty much in the same neighborhood and sometimes even the same block as their parents, dealing with a lot of the same issues and challenges that their parents dealt with. That’s probably two or three years ago. And then we really started digging into the edit.

At the end of the film, the screen shows the names of other victims of gun violence in the District in the years since Emmanuel was killed. Why did you think that was important to include?

CS: Well, what I lost was near and dear to me. But I know other people were lost too, and I didn’t want them to think that I’m selfish or I’m self-centered. I was trying to tell everybody’s story with my story, you know? Sort of letting people know that every day this goes on and nobody cares. Nobody even thinks about it. And maybe we can get a message to these people who pick these guns up and decide that they have to shoot to kill — maybe we can show them there’s a value to life. That life has a value and that problems don’t have to be answered that way.

The film stays really focused on your individual family’s story. But there are, of course, larger forces at play in your lives, like government decisions that have a cascading effect. What do you think the message of the film should be towards the D.C. Council or elected officials or members of Congress, people who have the power to change lives with the decisions that they make?

CS: ASAP.

So — urgency.

CS: Yeah. I know people can still have guns and all that, but they really have to find a solution to this problem. They really need to find solutions, because this is not the Old West and you know, I don’t know if this is their way of controlling population, but it needs to be addressed. It’s gone on for too many years.

DR: We’ve had great conversations with folks like Michael-Sean Spence from Everytown for Gun Safety, and he talks about how it’s not a mystery how to address these problems. There are proven methods that help substantially reduce gun violence in these neighborhoods. What’s missing is the political will to support programs that can help reduce gun violence. It might be funding a basketball center in a neighborhood. It might be, you know, putting a little more money into a school to have after school programs. And also [getting rid of] policies that put drug offenders away for long prison sentences, pulling them away from their communities, leaving their children without a parental role model.

People like Smurf — the film speaks right to this. Fortunately, a judge saw his potential and allowed him to remain in the community. And he’s flourished. He’s now a manager at that grocery store where you see him working in the film. He’s a great dad to his kids. The title 17 Blocks is a challenge to the people in the halls of power at the U.S. Capitol Building. And the D.C. Council, the Mayor’s office, to allocate resources in ways that can help people in these neighborhoods and help not just gun violence, but just create more opportunity across the board. And so we’re asking those in power to pay attention to the film and find ways to support these communities.

Cheryl, what was it like to see your personal journey on screen? That vulnerability that you showed in putting this out in the world — what has it meant for you?

CS: I’ve gone through so many things in my life, and I’ve seen the damage it’s done to me. I’ve seen the damage done to my children. I didn’t ask for this. So I was kind of grateful that someone else could see and hear me in another way.

17 Blocks is now streaming via various movie theaters.

This story was corrected to reflect the year Emmanuel Durant was killed.

Jenny Gathright

Jenny Gathright