Returning D.C. residents, criminal justice experts, attorneys, and elected officials urged the D.C. Council on Thursday to move on legislation that would simplify the process of sealing criminal records — but debated the details of proposed reforms, with some arguing that two bills before the Council don’t go far enough to support D.C. residents arrested for or convicted of crimes.

Instead, advocates favored record-sealing legislation recently introduced by At-Large member Christina Henderson, which includes broader reforms than those included in the measure submitted to the Council by Mayor Muriel Bowser. Bowser unsuccessfully tried to push a previous version of her bill through the Council in 2017.

The Committee on Judiciary and Public Safety held a public hearing Thursday on the Second Chance Amendment Act of 2021 and the Criminal Record Expungement Amendment Act of 2021 — two pieces of legislation that amend the city’s current record sealing laws, which are among the most restrictive in the country. Henderson’s bill, known as the RESTORE Act, was not submitted in time to be officially considered during the hearing, but several public witnesses leaned in favor of her proposed reforms.

Bowser’s bill, The Second Chance Amendment Act of 2021, would mandate the automatic sealing of criminal records for individuals who were arrested but never convicted of a crime (known as “no papering”) within 90 days — drastically shorter than the two to four years it currently takes.

About one-third of the 40,000 annual arrests in D.C. don’t result in convictions, but current law still requires extensive and complicated processes to seal these arrests from public view. Bowser’s measure would also decrease the time someone must wait to conceal their record after being convicted of a crime from eight years to five years.

Introduced by Ward 8 Councilmember Trayon White, the Criminal Record Expungement Amendment Act of 2021 (despite its name) has little to do with expungement, which means a charge or arrest is completely erased from a record. Instead, the amendment proposes expanding the eligibility for record sealing, where records are not publicly visible but can be available to the courts. White’s amendment expands the eligibility for record sealing to include first or second degree theft felonies, felony possession, and all misdemeanors. Right now, only one felony — failure to appear — can be sealed on a criminal record in D.C.

Rabbi Charles Feinberg, the Executive Director of Interfaith Action on Human Rights, praised the Council for taking up record-sealing legislation, but called the two bills an “insufficient step” to support D.C. returning citizens and people arrested for crimes — the overwhelming majority of whom are Black residents. Feinberg criticized the bills’ failure to include provisions for expunging criminal records for felonies and further shortening wait times, and for still maintaining complex language that might require a lawyer to understand.

“We haggle over how long the records of those returning from prison should be opened or when they can be sealed,” Feinberg said. “We put up one barrier after another that returning citizens have to navigate and somehow bypass in order to live and prosper.”

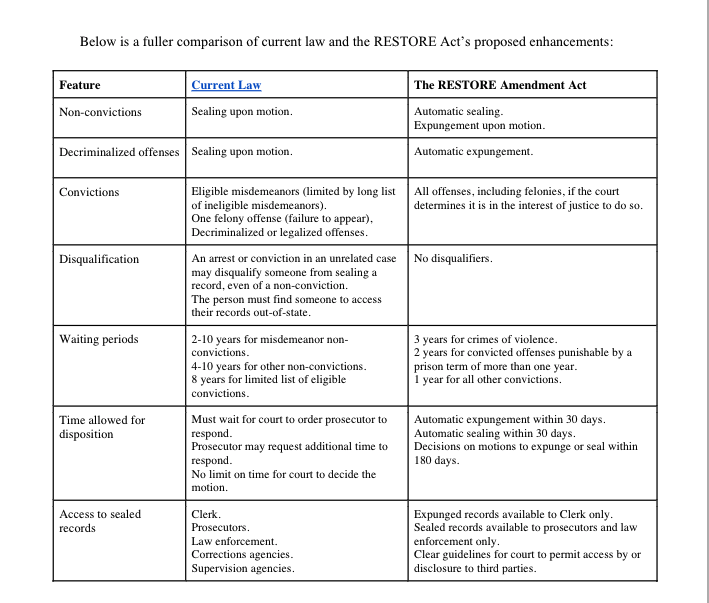

Henderson’s measure — the Record Expungement Simplification to Offer Relief and Equity Amendment Act of 2021 — aims to detangle the complex provisions within D.C.’s record-sealing laws, and further reduces the limitations of wait-times and eligibility beyond Bowser’s introductions.

Crafted with the guidance of the D.C. Justice Lab, a team of law and policy experts that advocates for changes to D.C.’s legal system, the RESTORE Act would allow expungement for all misdemeanors and felonies with a court’s determination, eliminate any disqualifications that may prevent record sealing for non-convicted cases, and reduce the longest waiting period for sealing of crimes of violence to three years.

“It is the RESTORE Act that is more broad than the two bills that are currently under consideration today,” said Richard Gilbert, an attorney with the District of Columbia Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “And I’m hopeful that… the Council will see that this is actually the bill that needs to be considering.”

Deputy Mayor for Public Safety and Justice Chris Geldart said Thursday that the mayor’s office is still reviewing Henderson’s bill, but urged the Council to support Bowser’s Second Chance Amendment Act.

Geldart did not support White’s bill expanding record sealing to certain felonies, instead touting a recommendation included in the mayor’s legislation, which calls for research into which felonies could potentially be eligible for sealing.

Ward 6 Councilmember Charles Allen, who chairs the Council’s judiciary committee, pushed back — arguing that much of that data already exists, and that waiting for a report could stall reform for years.

“We’ve been working on this for years to get to this point, I just envision that [research] process taking multiple years,” Allen said. “In my mind, I’m thinking there’s a compelling reason for us to try to move forward.”

Other government witnesses from Attorney General Karl Racine’s office and the United States Attorney for the District of Columbia supported aspects of the mayor’s bill, but offered further recommendations, like limiting automatic sealing in misdemeanor cases where a victim is a child, and a more conservative approach to expungement than Henderson’s bill proposes. The D.C. Public Defenders Service testified in favor of immediate and automatic sealing for non-convictions, and the ability to seal all convictions.

The discussion of three different record-sealing bills comes after the Council’s passage of other measures geared toward removing barriers for formerly incarcerated residents and reducing the lasting consequences of interaction with the criminal justice system. In December, the Council passed a bill that would allow some residents convicted of violent crimes before they turned 25 to petition for early release, and another that makes it easier for residents with criminal records to obtain certain job licenses.

One public witness who spoke on Thursday, Sunny Kuti, noted how difficult it was for him to find a job after being incarcerated as a youth, and supported automatically sealing records and expanding expungement for convicted charges.

“I’ve been on multiple job interviews where I was denied a job, because I was deemed unqualified to become a waiter, or to become a janitor. I was denied a job because of my past and my record,” Kuti said. “I’ve taken every step possible to rehabilitate myself to be released from prison, and to come [home] to direct discrimination, it makes me feel as though all my time was wasted.”

Henderson’s measure, introduced on April 1, has the support of Allen and six other councilmembers. It will first have to move through the Judiciary and Public Safety Committee before getting a vote from the full Council.

This story has been updated to more accurately characterize the position of the D.C. Public Defenders Service.

Colleen Grablick

Colleen Grablick