Five years of contentious debate finally came to an end Tuesday, when members of the D.C. Council unanimously approved changes to the city’s Comprehensive Plan.

The dense, 1,500-page document establishes the parameters of growth and development in the city over a period of 20 years. The plan itself doesn’t implement any changes, but it offers legally binding guidance to D.C.’s Zoning Commission as the body considers proposed zoning changes brought by private development firms and other groups seeking to develop land in the city.

In 2016, Mayor Muriel Bowser’s administration began the process of amending the plan, motivated by a series of legal appeals brought by activists and residents that used the Comprehensive Plan to block new housing construction. Over the next several years, the city gathered more than 10,000 responses from Advisory Neighborhood Commissions, residents, developers, advocacy organizations, activists, and others about how to tweak the plan’s language.

Over time, what the administration envisioned as a relatively minor, medium-term update transformed into a battle over racial equity, displacement, and the influence of for-profit developers over land use decisions in the city.

Ultimately, however, the document approved Tuesday is a win for the Bowser camp. It delivers 15% additional capacity for housing development, according to the administration, which has made housing construction a top priority. It’s also likely to clear a backlog of zoning decisions languishing at the Zoning Commission, paving the way for roughly 1,000 new housing units, not including ones not in the pipeline yet.

“When we set a goal to build a more equitable and affordable D.C. by adding 36,000 new homes by 2025, we knew how critical this update would be to bringing that vision to life. Now, we move forward, ready to create new housing — and new opportunity — across all eight wards of D.C.,” Bowser said in a statement trumpeting the plan’s passage.

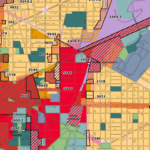

It’s also a win for supporters of denser housing types and transit-adjacent development in the District, including the nonprofit Coalition for Smarter Growth, which pushed for changes to the plan’s Future Land Use Map that would focus new development around Metro stations.

“Changes to the Future Land Use Map will encourage building more homes, especially near transit. This reduces pressure on existing housing, and helps moderate income households find a place to live,” wrote Cheryl Cort, the organization’s policy director, in a statement.

But the Bowser administration was bruised by an analysis that found its proposed revisions — many of which focused on ushering in new development — would exacerbate racial inequity in the District.

“The Comprehensive Plan, as introduced, fails to address racism, an ongoing public health crisis in the District,” said the report from Brian McClure, director of the Council’s recently established Office of Racial Equity, which analyzes legislation for its impact on racial disparities in the District. “It appears that racial equity was neither a guiding principle in the preparation of the Comprehensive Plan, nor was it an explicit goal for the Plan’s policies, actions, implementation guidance, or evaluation.”

That critique gave way to a slew of rewrites from Council Chairman Phil Mendelson’s office focused on affordable housing and a more intentional approach to rolling back decades of racist housing policy that have concentrated the city’s Black residents into unstable, unsafe housing that’s now a prime target for redevelopment. His office made further changes after Councilmember Janeese Lewis George (D-Ward 4) called for the plan to define “affordable” housing as homes within reach to families earning no more than 40% of the region’s Median Family Income, equal to about $51,600 a year.

By the day of the second and final vote on Tuesday, some of the plan’s most ardent critics on the council seemed largely satisfied by the latest version. Additional amendments explicitly defined “deeply affordable housing” as homes targeting households earning up to 40% of the MFI, and references to that particular band of housing are now found in multiple places throughout the text. Other changes focused on an equitable rebuilding of Barry Farm, a top priority for Councilmember Trayon White (D-Ward 8).

“My initial vote on this was ‘present,’ but today I’m voting ‘yes,'” Lewis George said ahead of the vote. “I think for D.C. to remain a diverse and inclusive city, we know we need to generate housing that meets the needs of D.C.’s lowest-income residents, and so far, I appreciate the language on just acknowledging we simply have not done a good enough job doing that.”

Some still found fault with the amended document, however. On the day the council voted to approve the plan, a dozen D.C. residents filed a complaint challenging the plan, saying officials failed to take into account community opposition. That suit remains pending in D.C. Superior Court.

Advocates have also been quick to point out that language in the Comprehensive Plan isn’t self-actualizing. To turn the text into actual policy, the Council must allocate dollars to priorities such as deeply affordable housing. “Now, we need to significantly increase public funding and focus these scarce resources on helping those with lower incomes,” wrote Cort with the Coalition for Smarter Growth.

As of today, the Comprehensive Plan is still not set in stone. Next, it must be reviewed for approval by the National Capital Planning Commission before it can go to the mayor’s desk for her signature. Then it heads to Congress for its standard 30-day review. Overall, the process of codifying the Comp Plan into law could take six months, according to the mayor’s office.

And that’s not all. The D.C. Office of Planning is already turning its attention to the next big milestone: a full rewrite of the plan. Required to be overhauled every 20 years, the document is due for yet another massive update in 2025. And that update could be even more consequential — and fraught — than this one.

This story was updated to include a statement from Cheryl Cort with the Coalition for Smarter Growth.

Ally Schweitzer

Ally Schweitzer